The 80-year-old priest, whose eyesight fails and steps falter, goes faithfully every day to the nursing home to visit his long-time companion. There are faded photographs in an album showing the two of them swimming in the ocean, tossed together on the Long Island sands of their mutual friends. There are pictures of him carving her Thanksgiving turkey, pictures of her opening his Christmas gifts. For years he brought two choice steaks from a local grocer for a late night supper in her apartment.

Now he goes to the nursing home every day around 4 and spoons ice cream and champagne through her broken lips. Then he turns on the tape recorder he has brought, and together they listen to John McCormack. When it is time to leave, he smooths her thin hair and kisses her five times on the broken lips, not without ambiguity, to be sure, and perhaps a certain loss of integrity. Perhaps a certain sense of it.

Eugene, also 80, brings his wife coffee in bed. Every morning Agnes wakes to a fresh brew in a Dresden cup and saucer from their life in Germany. Eugene sits on the edge of the bed while Agnes slowly sips.

“I have to do more and more for her,” Eugene says. “I want to, really.”

Later in the morning they sit together in the gooseberry garden. Eugene moves Agnes’ chair as the sun moves. Then he reads to her, the Jane Austen novels that she favors. When Agnes smiles, Eugene cannot tell if a breeze has touched her face or if some mishap has occurred in the Austen drawing room.

Slowly Eugene reads. Slowly the sun moves behind the trees. Sun and moon wax and wane; one day slides into the next. But Eugene does not move from Agnes’ side.

Neither does Sister Tess move from Sister Agnes Rose’s side. Tess is a professor emerita of biology; Agnes, a professor emerita of political science. Their enduring devotion to each other and to their students is legend. So are the parties they hosted in their campus apartment. When Agnes Rose ran for local political office, Tess knocked on doors, too. When Agnes Rose’s thoughts began to wax and wane, one thought after another sliding into oblivion, Tess packed up their lives and both moved to our congregation’s retirement home.

And so it happens. While the aging priest makes his way to the nursing home, and Eugene to his wife’s bedside, Tess gently wakes Agnes Rose to a new day. Then she helps her dress in the charcoal gray slacks, matching sweater and scarf from her professional days.

While the aging priest offers ice cream and champagne, and Eugene, a cup of coffee, Tess spoons finely cut noodles into her friend’s waiting mouth. Bits and pieces slide down Agnes Rose’s plastic bib, but no matter. Tess has an endless supply of noodles and love. Sometimes they swing easy in the courtyard. Sometimes Agnes Rose lifts her head to bird song as if to some remembered time. Tess treasures these moments. She knows what Eugene and the aging priest know, what Shakespeare expressed so well:

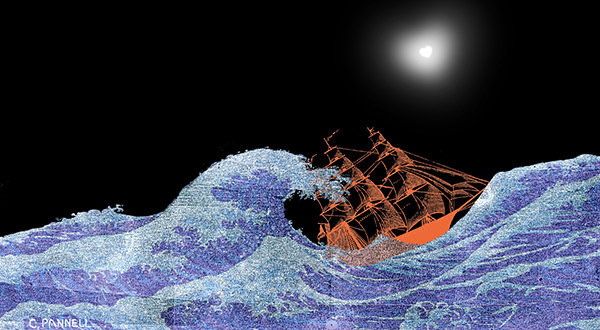

Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds. . . .

Oh no! it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wand’ring bark.

Joan Sauro, CSJ , is the author of several books, including the forthcoming We Were Called Sister, whose title essay was awarded the prize for Best Essay 2014 by the Catholic Press Association.