Sorting through my home office always turns up pleasant surprises, including books I really should read now that they’ve emerged from long-ignored stacks. The timing was especially fortunate this summer because my rediscovered Living Gently in a Violent World: The Prophetic Witness of Weakness offers an antidote to the toxins exploding all over the news. I blame those toxins of tension, relativism and self-centeredness, which have leaked into presidential campaigns and civil unrest, for the fading of the hope and peace Americans once found in democracy and servant-leadership.

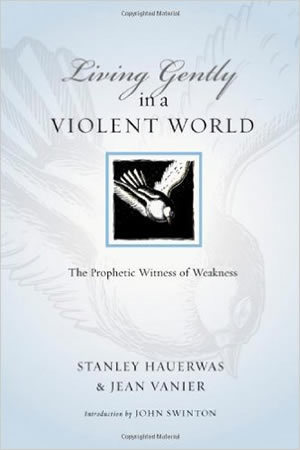

You, too, might want to pick up Living Gently, the 100-page gem published in 2008. Stanley Hauerwas and Jean Vanier capture key principles about the joy of gentleness from a unique field of experience. It’s not a feel-good book in the conventional sense. In the best spirit of Catholic paradox, it talks about finding peace in brokenness. Like a cookbook for those fighting cancer, it unveils recipes to restore the healing connections found in the realities of everyday life. These recipes reflect the “human ecology” Pope Francis discussed last year in his encyclical, Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home.

I’ve begun to think living gently is our only reliable source of hope and peace these days. Living Gently co-author Jean Vanier embraces human-scale reactions, reflecting upon his experiences as founder of the international movement L’Arche (The Ark). The movement, started in the 1960s, consists of inviting people with intellectual disabilities to form a household along with brothers and sisters who don’t share their disabilities but who make long-term commitments to walk the journey with them. It’s a radical aspiration for real life and total trust in a “common home,” ready to invest great persistence to yield joyful, compassionate service.

When I purchased this book a few years ago, I was reacting to such an inspiration found here in South Bend. A “Friends of L’Arche” group, although not successful in finding a physical home to be shared by people with and without intellectual disabilities, held gatherings locally to build bridges across the gaps of self-isolation. These gatherings evoked hopes of connection through brokenness and strength through weakness that resonated with me.

Now, with my second reading this summer, the book seems bolder, less about a local act of witness than about a national state of urgency.

Vanier’s chapters still add the comforting spices of smallness and humility, but now I hear a warning in the chapters by Hauerwas, professor of theological ethics at Duke and former theology professor at Notre Dame. He applauds the offering of healing and trust as key steps toward dialing down the rancor of our policy and politics. But he goes further with a call to make our theology an explicit part of the healing recipe.

The spirit of gentleness we bring to the party (including political parties) must represent “the gentle care exemplified by Jesus in washing his disciples’ feet — that gentleness exemplified in L’Arche,” unapologetically witnessing “to the One who would save through the cross. Otherwise, how would the world know that our loneliness has been overwhelmed and it is possible for us to trust one another?”

I’m now re-reading Living Gently in a Violent World as a cancer-fighting cookbook where the recipes are just one corrective for our politicians, our leaders and me. Today’s news of confrontations reflects the assumption that only secular tools will mend our sense of incomplete identity and purpose. Authors like Hauerwas and Vanier can help us interject humility, service and patient hope while too many politicians tout national greatness, instant gratification and cruel attacks on the dignity of their opponents.

Books like this, rooted in insights from the 1960s and before, help me realize the cure must go even deeper. Today’s dysfunction multiplies broken connections among people and ideas, love and truth, faith and reason, and reality and problem-solving. God is the sine qua non in our public discourse — partly because He is the revealer and healer of our degraded ecosystems. Pope Francis has spotlighted in his writings that God infuses mercy and joy into our flawed implementation of care for creation (Laudato Si’), hope for salvation (Evangelii Gaudium) and sustainable love (Amoris Laetitia).

I saw from the start that L’Arche is one of faith’s many forces for training us in the manners needed aboard a shared ark. Now I’m rediscovering this ark as a shelter for survivors who must dig deeply into faith so they can arise to create “a new normal,” ready to unpack joy and hope once all the toxins have been washed away.

Bill Schmitt is a freelance writer/editor who has written extensively on higher education, K-12 education, and Catholic history and values. He is based in South Bend, Indiana, and his website is OnWord.net.