“Mommy, the darkest people get shooted and killed and sometimes the little bit lighter ones, too,” 4-year-old Quest McEwen mused a few months ago as his mother, Tessa McEwen ’05, listened in shock. “So, that’s why I want to be good,” he continued. “Maybe I shouldn’t talk like this so I don’t get died.”

Quest wasn’t done fretting, however, when on a more recent morning, he worried aloud that he didn’t know “if Daddy’s dead,” because his father, Jelani McEwen ’05, had come in late the night before following after-hours volunteer work in their Chicago neighborhood.

Like scores of black and brown families throughout the United States, the McEwens are struggling with the delicate-but-brutal balancing act of protecting their children’s innocence, while educating them about the realities of what it means to be black in this country.

For these parents and their children, “The Talk” has nothing to do with birds and bees. It is about surviving police encounters, being aware of your rights and learning how to live within a complex, systemic, centuries-old framework of race-based prejudice, violence and discrimination.

The Talk is akin to a rite of passage for many African-American children, especially boys and young men. Essentially, they are taught how to behave in the presence of police to mitigate potential harm: no sudden movements, don’t question why you’re being stopped, comply with all verbal commands, never raise your voice.

Make it home alive.

It is a discussion many black parents consider a necessary evil, dreading the day when their children go from innocents to threats in the eyes of a historically racist society. And it is a discussion many of their white co-workers, friends and neighbors may be ignorant about.

“I had a conversation about The Talk with two of my neighbors — and I don’t get into this with a ton of people, especially white people,” says Christy Greene ’96, who lives in East Amherst, New York, with her husband, Allen Greene ’00, and their daughters Rian, 11, and Seneca, 4, and son Samuel, 9. “They said, ‘Are you going to have a conversation with Samuel about this? Are you really worried about this?’ They gush over him because he’s playing at their house, and they think he’s handsome and polite and his parents are professional and have advanced degrees. But it matters that his skin is brown and that the perception of that could cost him his life. Am I going to have a conversation with him? Does it upset me? Yes. But I want my kid to come home! If this is about whether Samuel winds up in the hospital or winds up in the morgue, that is real. He has got to come home to me.”

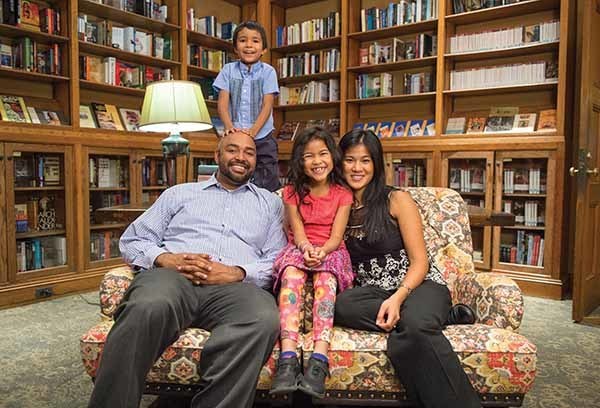

Tessa McEwen, who is Filipino American, and Jelani, who is African American, say they were shocked to hear the heartbreakingly adult musings of their son — not because of what he said but because he was only 4. Quest, now 5, and his 8-year-old sister, Via, are already growing acutely aware of how instances of police brutality, injustice, violence and racial discrimination impact children — and parents — who look like them.

“Hearing him wonder am I dead — I was floored to hear how aware they are,” says Jelani. “They’re aware that some of the people who get killed have kids. They saw Alton Sterling’s son crying, and we talked about that. They are aware of all these things going on with black dads and black parents. As they grow, they need to know about the America that will not accept them for who they are, yet you want them to be committed to living life on their terms in the face of these things. I wrestle with how explicit and how concrete I want to be. They’re sponges and we, as adults, undervalue how much they’re really hearing.”

And really feeling.

When the McEwens asked Via this summer what she understood about Black Lives Matter in the midst of the protests and outrage that ballooned following the police killings of several unarmed black men, she responded abstractly about a concrete concept: inequality.

“I’ve only seen the signs, and I think it means that white people think they’re better than black people,” she told her parents. “I think Black Lives Matter means that black people should be free and they matter just like white people.”

Tessa reports that Via also weighed in on the presidential election. "I am sad that Donald Trump is president. He’s so mean. And he said things that weren’t true,” the young girl commented. “I think that he would take away my family’s jobs and black people’s jobs.” Turning to her brother, Via told him, “He doesn’t like us.”

Black parents struggle with explaining this sense of antipathy and inequality while ensuring, in turn, that their children remain both self-confident and accepting.

“It’s been a really fine line to walk, explaining the reality of the situation but not scaring them — not making them so distrustful of white people or cops,” says Christy Greene. “I think it’s wise to be open, but when they walk away from you and go to their rooms, or get on the bus and get to school, they’re repackaging it all in their minds, and we’re not there to help them unpack.”

Christy, whose mother is black and father is white, is especially concerned about her son, who might not always be seen as the child that he is.

“It’s sad that I tell my son, ‘When you’re walking home with your buddies, be careful’ . . . They weren’t old enough to remember Trayvon [Martin], but I explained to my son that this boy was just a little bit older than you — he had a Gatorade and Skittles, like you sometimes do — and just because he had a hoodie on and just because his pants were sagging, he was killed. I hate that as much as I try to give my kids a voice, I have to teach them they have to silence that voice sometimes.”

Jelani remembers having in his teens a similarly disheartening conversation with his father.

“He walked me through all of the situations in life where I need to make myself smaller to be safe. He told me, ‘You cannot give police a reason to go any further with you. If they pull you over, be compliant, don’t raise your voice, don’t ask questions. Just do what they ask of you.’ I was frustrated because it was unfair. I was 16 years old, just out of boarding school, and I’d just come home to Chicago. He’s still coaching me on how you can’t be your biggest, boldest self.”

Phyllis Stone ’80 and Jim Stone ’81 of Somerset, New Jersey, gave their son, Alex, 30, the same talk when he was younger, and they are seeing the cycle repeat itself as he raises his two teenage stepsons.

“It never occurred to me that several generations later, he would be in a position to have the same conversation with his sons. That’s a surprise to me, for sure, even though we’ve come a long way and racism has changed over the years — but it’s a surprise to know that generations later, The Talk hasn’t changed a whole lot,” says Phyllis, a member of Notre Dame’s Board of Trustees and the University’s second African-American cheerleader. “We’re told do all of these things — keep your hands where police can see them — but those things don’t even apply anymore. So there’s a little bit of confusion.”

Confusion even for their grown son, whom the Stones say has been brutalized — and traumatized — during encounters with police officers on several occasions throughout his life.

“There are stories about him being stopped, and being physically and verbally abused and being roughed up that he can’t even tell me,” Phyllis says. “With all of the events in the media of black men getting killed by policemen — I forget which incident it was — he called me one day and said he was scared to come out of the house. He is clearly going through something right now that’s a little bit different from when he grew up, even though he was stopped by the police countless times and wasn’t charged with anything, ever.”

Jim Stone says he has experienced trauma similar to his son’s, being rendered “speechless” when police pulled him over and harassed him as he was en route to a high school homecoming dance in his hometown of Seattle in the 1970s.

“Obviously I’m dressed up and my date was dressed up and they asked my date if she was with me of her own free will. That was an eye-opening situation,” he says, even after his father had given him and his four brothers The Talk. “I was roughed up a little, both mentally and physically, and it took me a while to get over that. It might have been a year or two after college that I felt strong enough to talk about it with my parents. My dad had several conversations with me that something like this might happen.”

The Talk is both a protective tool and an equalizer of sorts, as black parents must explain to their children that disproportionate police brutality is something that can and often does happen to black men and women, regardless of their income level, education or status in society.

During his remarks at the convention of the International Association of Chiefs of Police in San Diego in October, Terrence M. Cunningham, president of the organization and chief of police in Wellesley, Massachusetts, acknowledged “the actions of the past and the role that our profession has played in society’s historical mistreatment of communities of color.”

In an email to The Washington Post following that speech, Cunningham continued: “Communities and law enforcement need to begin a healing process and this is a bridge to begin that dialogue. If we are brave enough to collectively deliver this message, we will build a better and safer future for our communities and our law enforcement officers. Too many lives have been lost already, and this must end. It is my hope that many other law enforcement executives will deliver this same message to their local communities, particularly those segments of their communities that lack trust and feel disenfranchised.”

However, that feeling of invalidation is one of the intangibles black parents are tasked with explaining to their children — even when they haven’t come to terms with those emotions themselves.

Braynard “Bobby” Brown ’00, ’06J.D., who lives in South Orange, New Jersey, with his wife, Emily Bienko Brown ’00, ’03J.D., and their sons Braynard II, 6, and Thatcher, 4, recalls how defeated and helpless he felt during his first encounter with police as a teenager in his hometown of Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

“I had a weapon drawn on me in high school, as an All-American two-sport athlete, hearing from everyone that I’m the best thing in the world,” he says. “I was taking my girlfriend home one night, and I wasn’t that familiar with her neighborhood. I literally took a wrong turn down an alley, and the first thing the officer does is draw his weapon. That was a totally life-changing moment.”

During the encounter, Bobby says he drew upon the lessons he learned during The Talk to help guide his actions.

“Saying all the right things, hands on wheels — all the things my mother taught me — which made the officer even more volatile. I was physically and emotionally shaken; I had this gloss of naiveté. I’ll never outgrow that — I remember that like it was yesterday. It was this time in my life when I thought I had done everything right. I came from a tough neighborhood and had done well academically, but, to him, I was dangerous. He wanted to belittle me and take away any dignity that I had. I can still hear his voice, because he truly wanted me to feel that I was an inferior human being. I was blessed to have a mother who always reminded me that I could do all things.”

Instilling self-confidence, reinforcing positivity and letting black children know they matter is another key component of The Talk, says Marcus Jackson ’06, a widower with a 3-year-old son and 14-year-old stepson.

“The Talk with [my stepson] was more about looking at history and where we are today and reminding him that you’re at the age where people won’t like you and it won’t be justified,” says Jackson, a native of Hammond, Louisiana, now living in East Windsor, New Jersey. “You can’t let it slow you down. Even with all of that hate, we as black people have always been overachievers. I tell him to make sure you’re in the right at all times, because we’re not afforded the same room for mistakes.”

‘At some point we have to have a real conversation,’ Brown says. ‘We have to start taking this seriously, or else we have failed ourselves as a country and as a faith.’

But even the light of positive messaging can be dimmed by the darkness within our society, he adds.

“As I look at my children, I see that sense of hopelessness. We’re trying everything to show we’re not a threat, and we’re still a threat. That hurts the most.”

Jelani McEwen knows that hurt well, explaining that even young black children are seen as threatening, something he thinks about both figuratively and literally when it comes to his size.

“I am 6-foot-2-inches, 270 pounds — I’m a huge person, and I’m probably one of the sweetest, kindest men, yet when I walk forward, people are afraid of me and I see it. My dad’s words did help me — what it means to walk around in my body and how people observe that. I have that talk with my dad still to this day about how to make myself digestible for people.”

Meanwhile, other physical attributes have come into play for the Greene family, where Christy, who is fair-skinned, says her children not only notice the spectrum of skin colors within their brood but equate darkness with potential danger.

“Allen is as a dark as they come, and they know Daddy travels every single week. I let them know that when Daddy is on the road and if anything happens, Daddy is going to think and be smart. They’re asking me, ‘What do people do to get shot?’ and I’m telling them they weren’t doing anything that warranted their being shot and if Daddy ever gets pulled over, he knows how to handle himself. Absolutely, they know the cities where things have happened, so they ask me where Allen is going.”

Because Christy is the lightest member of their family, her children don’t worry about her well-being in the same way.

“I had to go to Charlotte for a funeral and took my youngest daughter with me. Rian said, ‘Mom, are the cops killing people there? Because I don’t want them to hurt Seneca.’ My kids don’t think anyone is going to hurt me because I’m a ‘peach’ person. They know my mom is black, but they think I’m immune to this.”

Jim Stone says no one — black or white — should feel immune to these issue, even when The Talk or any other discourse about race becomes uncomfortable.

“When I think about Notre Dame and how that’s had a big impact on my life, if Notre Dame is going to be what they say they are, we need to have the conversation. When you have the conversation, people look at you like, Are you serious? And I say, ‘Yes — it’s happened to me.’ It’s hard for them to realize when it hasn’t happened to them.”

Getting comfortable with being uncomfortable is key to catalyzing positive change when it comes to attitudes about race and racism, Bobby Brown adds.

“The risk for me is real; this isn’t a myth. I have no reason to lie about this. We can find all of the reasons to poke a hole in certain demonstrations, but at some point we have to have a real conversation,” Brown says. “We have to start taking this seriously, or else we have failed ourselves as a country and as a faith. It’s that binary: We either start taking steps to create a solution or we fail. And how many more generations are we going to fail?”

Arienne Thompson Plourde and Amelia Thompson are sisters from Memphis, Tennessee.