On November 9, 2005, Notre Dame’s third professional museum director, Chuck Loving, and his staff, celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Snite Museum of Art. During 1980 to 2005, The Snite Museum of Art emerged from an all-too-often-expressed “the best kept secret” reputation, earning its place among the elite of university art museums. It owes much of its success to hundreds of individuals and organizations who, in partnership, formed a great team.

That team was filled with visionaries who built, sustained and promoted the O’Shaughnessy Art Gallery and The Snite Museum of Art far beyond even the loftiest of expectations. On this anniversary, we celebrate Rev. Anthony J. Lauck, CSC, Notre Dame’s first professional museum director (from the early1950s until 1974) and the man who set the example for the museum professionals who followed; the benefactors who displayed uncommon generosity in their donations of art and cash; volunteers who became “tenured” teachers in the museum’s galleries; a lively membership organization, the Friends; and two administrations whose imagination and trust inspired the museum’s growth. Nor should the staff be forgotten; many of their professional careers at Notre Dame predate the Snite Museum’s 1980 opening. The museum’s four curators of collections have labored nearly 80 years combined. Curator of Education Diana C.J. Matthias ‘79 and Registrar Robert Smogor began their careers shortly after the Snite opened in 1982. Few university museums can boast of such continuity and dedication.

As director of the O’Shaughnessy Hall Art Gallery and the Snite Museum of Art (1974 to 1999) and as a devoted student of Father Lauck, my role in Notre Dame’s museums was determined early—to build a pre-eminent museum. For nearly four decades I was fortunate to work with wonderful individuals. And, more important, I worked for a university that stood for excellence. Unlike many university museum directors, I did not have to raise money to cover general operations. It was not in my job description—the galleries would always be open. Proceeds from the directors’ fund-raising efforts would be used to enhance collections and programs.

Collecting can be traced to the early years of Notre Dame’s founding. An institution with its rich history also had its collections of art and artifacts. Tragically, much was lost when an 1879 fire reduced the Main Building and its contents to a pile of smoldering ashes. Even though Notre Dame’s founder, Father Edward Sorin, CSC, and many Holy Cross brothers rebuilt it, beginning before the ashes cooled, art was important to the French priest. Five years earlier Father Sorin convinced the pope to send Luigi Gregori to Notre Dame where, in 16 years (1874-1891), the Italian artist painted the stations of the cross and several murals in Sacred Heart Basilica, the Columbus cycle (1880-1881) in the Main Building, as well as a host of easel-size paintings, religions scenes and portraits of historical figures. In 1880, Notre Dame’s first Distinguished Artist-in-Residence had access to some Native American artifacts owned by the University, which he employed as props in his Columbus murals. When Gregori returned to Italy in 1891, he also left behind a collection of average quality, mid-18th century Italian drawings.

Collecting at Notre Dame from 1875 to 1925 had a few noteworthy moments. In 1899, the “Buckeye missionary,” Reverend E.W.J. Lindesmith, donated several wooden crates filled with Native American artifacts gathered during his work in the West. In the 1910s and ‘20s, Notre Dame attempted to build an art collection that reflected its Catholic character. Sadly, even though the early collection, consisting of the Braschi Purchase (1917) and Wightman Memorial Collection (1924), bore the names for the great Old Masters, the canvases were often poor copies. However, with pride and much fanfare, they went on view in the top floor of the University’s library (today the School of Architecture).

Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, president emeritus, recalled his student days when he had to climb three flights of stairs and locate a key to the Wightman Memorial Art Gallery. After turning on the lights, he saw a collection of “impostors,” paintings with overly ambitious, sometimes embarrassing attributions. The poorly illuminated paintings were hung under windows, over water fountains and between stacks of books.

It wasn’t a tragedy that the University’s most important treasures, the Native American objects in the Lindesmith and other early collections, went into dead storage. Indian artifacts were not in vogue during the war years, and by keeping them in dead storage the University actually maintained them in a better state of preservation. Today several pieces of consummate quality form the core of a fine Native American collection.

Serious collecting begins

Reverend John J. Cavanaugh, CSC, planted the first seeds of building a serious collection of art. He began by working with the Saint Paul, Minnesota, philanthropist and president of Globe Oil and Refining of Minneapolis, Ignatius A. O’Shaughnessy. Together they planned O’Shaughnessy Hall, a building that would house the College of Arts and Letters and the Art Gallery, a space designed to professionally house and exhibit art. In 1952, Cavanaugh turned over the presidential reins to the 35-year-old Hesburgh, the same year the O’Shaughnessy Hall College of Arts and Letters opened its doors.

Besides accepting the daunting task of running one of America’s most celebrated and revered institutions of higher education, Father Hesburgh received some unusual instructions: “Father Cavanaugh directed me to visit three widows of Notre Dame trustees, Mrs. Keenan, Mrs. Stanford and Mrs. Fred J. (Sally) Fisher.” He did.

In particular, Cavanaugh asked Hesburgh to take Sally Fisher dancing. A surprised Hesburgh responded “I don’t know how to dance anymore.” Yet, it wasn’t long before he found himself flying to New York, picking up two friends—a married couple—and Sally Fisher. The four went to the Waldorf Astoria, and while Guy Lombardo’s big band played, Hesburgh remained on the sidelines, certainly one of those rare times he found himself in that position.

In a subsequent meeting, Fisher donated a quality collection of Old Master paintings to Notre Dame. Finally, Notre Dame was in a position to demonstrate how serious it was about elevating the status of art on campus. Several 18th century French and English portraits are today among the museum’s master works. In 1967, my predecessor, John Howett, wrote: “The Fisher collection added a necessary core of first-rate paintings to the Notre Dame holdings.”

Highlighting the gift was Francois Boucher’s Offering of the Rose, painted in 1765, the same year he was appointed the First Painter to the King of France. It has delighted hundreds of thousands. In 1968, Dr. John Maxon, director of the Art Institute of Chicago, called it Notre Dame’s most important painting. Thirty years later, a young man chose Junior Parent Weekend to successfully propose marriage, in front of Boucher’s Offering of the Rose.

By the 1970s, under Father Lauck’s inspired leadership, the art collections and programs had outgrown the 16,000-square-foot Art Gallery. In 1971, attendance soared to more than 52,000 visitors. The vaults overflowed, numbering between 3,000 and 4,000 works of art, including an interesting collection of Medieval Madonnas. Lauck, who had served as chairman of the Department of Art and the director of the gallery, stepped down as chairman to concentrate on directing the Art Gallery. With facilities designed to properly preserve and exhibit art, the collections experienced a period of significant growth and quality. According to surviving records, the collections numbered over 300 works of art in 1934 and about 1,000 at the time of Hesburgh’s meetings with Sally Fisher. By 1966 and the publication of Handbook of the Collections Art Gallery University of Notre Dame, objects numbered about 3,000. A decade later, the year of the Snite gift to build a new museum, the collection had grown to 4,000 objects.

Meeting the Snites

By 1974, it had become obvious that we needed to expand our facilities. We faced several problems. Notre Dame had declared a moratorium on the construction of new buildings. This, coupled with the cost of even an addition connecting the O’Shaughnessy Hall Art Gallery to the Ivan Mestrovic Studio, would be expensive. The answer to our problems was Colonel Fred B. Snite of Chicago and his family. I first met the colonel in 1967, on a cold, windy football Saturday when he brought two Old Master paintings, proposed gifts to the Art Gallery. After unloading the blanket-wrapped canvases from the trunk of his automobile and transferring them to a cab to transport them from the Morris Inn to the Art Gallery, he paid the $5 fare and carried one of the canvases the last 50 yards. At the time, Colonel Snite was a proud man whose age was in the upper 80s. I was impressed with his strength and pride and was convinced that his name should appear on our “addition.”

We met with Fred Snite and his family several times to discuss funding. During an April 1975 visit to Colonel Snite’s winter home in Miami, Curator Richard J. Conyers, CSC, and I had a successful meeting with the family. They agreed to give $2 million for the construction of a building that “68,000 would see every football Saturday.” While this may have been a point which convinced the Colonel that a museum would make an important contribution to the Notre Dame experience, he was much more interested in having the world know about the role that he and his son Frederick, confined to an iron lung for 18 years, had in conquering the dreaded disease—polio.

The Snite family and Notre Dame had to overcome obstacles in achieving the shared goal of the “addition.” On McConyers’ and my Friday the 13th flight home, the pilot announced that we had some unwanted baggage aboard the plane. We made an emergency landing in Atlanta; I left my row-13 aisle seat and headed to the exit with a copy of our 13-page proposal. After deplaning, we stood in the middle of a field, far from the terminal, and watched a silver truck pull up. A group of orange-clad men removed a large silver container from the hold of the plane. To this day I do not know if the “unwanted baggage” was a bomb or not. The stewardess certainly thought it was.

The adventure of the colonel’s gift continued eight months later. After his company, Local Loan, sold to the Mellon Foundation, the family agreed to travel to Notre Dame to make the grand presentation. We also planned to have Colonel Snite and his family turn the first spade of dirt. But winter came early. Our biggest concern was getting the spade into the frozen ground. Prior to the Snites’ arrival, we managed to dig up sufficient turf and mix hay with it. We had a five-handled silver-plated shovel, one for each member of the family and Father Ted. While our problem was relatively easy to solve, the Snite family—the Colonel, Mary Loretto. Terrence Dillon ‘32 and Tessie Snite—had a near disaster on their trip from Chicago. A semi dumped a load of steel in front of their car, narrowly missing them.

Noticeably shaken, they arrived two hours late. After a short ground-breaking ceremony and lunch, Colonel Snite, with a big smile, presented his gift and asked Father Ted: “Do you know why I waited to sign the check now?” Father Ted answered “No.” The colonel responded, “So the good Lord would get us here.” Father Ted’s response was immediate: “Colonel, how are you getting home?”

With the promise of a new facility the collection more than doubled, ballooning to about 12,000 in 1980, the year The Snite Museum of Art opened. According to the museum registrar’s records, 25 years later the collection numbers 22,000 objects.

A cadre of benefactors

The remarkable growth of the collection was due in no small part to continuity, teamwork, close friendships and the 52,000 square foot “addition.” For about a quarter of a century, beginning in the 1950s, Father Lauck had set the stage for those who followed. He developed a strong cadre of dedicated benefactors. During his tenure, principle support came from three cities—New York, Chicago and his hometown, Indianapolis.

Few of the museum’s early benefactors were alumni. In our 1969 Benefactors at Notre Dame catalogue, Lauck postulated that the Irish were generally not collectors—they were writers. He found that the strongest benefactors were often Jewish, and he courted them religiously. In Chicago, Lauck and a member of his acquisition committee, Professor Thomas Stritch, were frequent visitors to the home of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Randall Shapiro. There they saw breathtaking Picassos, Matisses, Miros and other works by pivotal figures of 20th century art. As early as 1954 the Shapiros rewarded the Notre Dame duo and the Art Gallery by donating important works, most notably the powerful watercolors by the German Expressionists Max Pechstein, Eric Heckel and Emil Nolde, as well as sculptures by the Englishman Henry Moore. The Shapiros’ donations of 20th century art came at a time when gifts to Notre Dame were more often than not religious in character.

Lauck was also successful in his hometown of Indianapolis. H. Nelson Deranian, a retired Washington lawyer, returned to Indianapolis in 1954 and then donated one of the museum’s most important acquisitions, Claude Lorrain’s Rest on the Flight to Egypt. He had planned on presenting the painting to Washington’s National Gallery of Art, but Judd Leighton of South Bend and Lauck teamed up and convinced Nelson that Notre Dame’s Art Gallery would be a place that would welcome and exhibit the painting on a regular basis. Like Lauck’s relationship to the Jewish collectors in New York and Chicago, it is an early example of the adage “People give to people.”

While Notre Dame was known for its religious art, in retrospect the Art Gallery’s most important examples were creations of the American West. During the early 1960s, networking between Father Hesburgh, his friends and alumni created a significant collection of Western art. In 1962, C.R. Smith, chairman of the board of American Airlines and an important collector of Western art, offered Father Ted a choice—$50,000 or Charles Marion Russell’s The World Was All Before Them (or The Romance Makers). He chose the latter, a painting that was called by scholar Fred Renner “the second best picture ever painted by Russell.” It is also the Snite Museum’s most valuable painting.

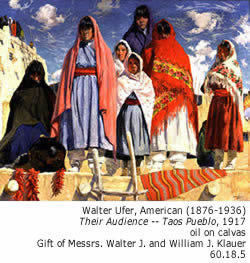

John T. Higgins, class of 1927, found that four canvases painted by his brother Victor in Taos, New Mexico, were too large for their modest-size Birmingham, Michigan, home and donated them to his alma matter. At the same time, brothers Walter J. and William J. Klauer were faced with a problem of critical proportions. They had sold their Hotel Julian in Dubuque, Iowa, that was decorated with 20 large paintings by Walter Ufer, another Taos artist. With no place to show or store the expensive paintings, the Klauers phoned Father Jerome Wilson, CSC, executive vice president for business affairs. They told him that Notre Dame could have the paintings if they were removed from the hotel by midnight that day. Even though the Klauers’ annual gifts included much-needed equipment like a Klauer Manufacturing-produced snowplow, and Father Wilson knew nothing about the artist, the priest dispatched the truck on a 500-mile round trip to Iowa. Today Their Audience—Taos Women, one of Ufer’s most important canvases, is considered to be one of the museum’s masterpieces. In the 1990s, the paintings by Higgins and Ufer were the focal pieces in major traveling exhibitions.

The addition of the Bronco Buster by Frederic Remington, an icon of Western sculpture, as well as additional paintings and sculptures by Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, George Winter, and a dozen more watercolors and oils by Higgins, ranks Notre Dame’s Western holdings as good as any university collection west of the Mississippi.

Advisory Council begins

In 1968, Father Lauck formed an advisory council. This was one of the earliest, finest and most effective university art museum councils in the country. A founding member and distinguished librarian of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, summarized Lauck’s persistence—"he wouldn’t take no for an answer." A distinguished assembly of museum directors, collectors and friends also accepted Lauck’s invitation. Their good work led to the collection’s growth, challenging exhibitions and University approval to build the Snite Museum of Art.

The council met twice a year—working three days, frequently returning their football tickets so they could spend their valuable campus time in the Art Gallery. Besides offering excellent counsel, they were also magnificent benefactors. One of their first jobs was to examine the entire collection, ranking it according to quality and appropriateness to the art galley’s mission. They provided the staff of the Art Gallery with an effective program to finally purge the collection of remaining “imposters.” After 25 years, the Art Gallery was able to rid itself of a stigma that characterized so many university museums—that of being a dumping ground for works of lesser quality and relevance.

Advisory Council members also began to look into their own collections to see what would improve the quality of the Art Gallery’s holdings. During a 1968 meeting, New York collector May E. Walter, without fanfare or audience, outlined her plan to donate her entire collection of modern art to Notre Dame. I was stunned and euphoric. Many times Father Lauck and I had visited her home at 725 Fifth Avenue and marveled at her wonderful collection. During the years following, Walter donated some of the museum’s most important 20th century sculptures, paintings and drawings. And on November 9, 1980, she helped us celebrate the opening of the Snite with the donation of Joseph Alber’s Homage to the Square—Compliant, an important canvas by Yale University’s most influential educator and color theorist.

When May Walter died in 1992, I had the sad task of traveling to New York to supervise the packing of her entire art collection. She had kept her promise; her bequest included paintings by Jean Metzinger, Joan Miró, Natalie Goncharova, among others. Our 20th century holdings had been promoted to a level of significance worthy of the space devoted to it.

As Walter Beardsley of Elkhart, Indiana, closed his office in Miles Laboratory, he wrote “Notre Dame” on yellow stickers affixed to the frames of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Blue and Rufino Tamayo’s Man with a Guitar. When Al Nathe saw George Rickey’s kinetic sculpture missing from its pedestal in the museum’s courtyard, he commanded: “Bring it back!” When Dorothy Griffin learned that Lauck was saddened (as was this writer) when the museum couldn’t afford William Zorach’s handsome reliefs in walnut called Family Group, she provided the funds for their acquisition. Such stories of Advisory Council members’ participation could fill volumes.

New Yorker Janos Scholz, professional cellist, collector and educator, made Notre Dame his pet project. As one of our most active Council members, Janos recognized that we had a need he could satisfy. In the 1970s, Notre Dame’s Art Department’s photography program, guided by Professor Richard Stevens, was beginning to flourish. In light of this and the new director’s passion for photography, Janos came to our rescue. He began to present large numbers of European photographs to Notre Dame. His collection focused on the early years of photography, 1840 to 1875. From 1974 until his death in 1993, the Art Gallery’s collection grew from one photograph—and that slipped into the collection on the back of a mount of a Luigi Gregori drawing—to more than 7,000 images.

In 1980, I visited Daniel Wolf’s photography gallery in New York. While we had a good collection of Robert MacPherson’s European views, I saw his stunning Waterfalls at Tivoli, and I knew this classic image belonged at Notre Dame. Unfortunately we didn’t have $1,250 in our budget. Expenses related to the construction and installation of the Snite had drained all of our resources, and I had to pass on it. During a subsequent visit to the gallery, I was dismayed to learn that it had been sold. When I spoke to Janos about my experience, he responded with his characteristic jovial smile: “Don’t worry my boy, it is yours.” Janos’ generosity also compelled me to hire a full-time curator of photography, Stephen Moriarty ‘69, ’80M.A.

Deciding on collections

In the late 1970s, The Snite Museum was in its final planning stages. Council member Stephen Spiro had met Cleveland residents Muriel and Noah L. Butkin in the Shepherd Gallery, New York. Muriel collected French drawings, Noah French oil sketches, both areas that Spiro specializes in. With these shared interests and passions, over the next several years Spiro, along with his wife, Judy, were frequent visitors to Cleveland. They formed a close friendship with Butkins. Trip after trip, they brought wonderful Dutch paintings, drawings, English silver, sculptures and, of course, French oil sketches back to Notre Dame. Tragically, before Noah ever saw Notre Dame, he suffered a heart attack in the winter of 1980. He died a day later, but not before he and Muriel made a decision. As Noah was on the board of the Cleveland Museum of Art, it would receive their large paintings, but Notre Dame would be the beneficiary of the oil sketch collection. No single gift would contribute more significantly to Notre Dame’s international reputation.

Even before the Butkin bequest, we planned a substantial space for 19th century European art. Our ability to show a large percentage of this unique collection at one time, curated by Spiro, was also a factor in Butkins’ decision. They also decided to make an annual cash gift to Notre Dame to add to the collection—the number of acquisitions purchased through their generosity now numbers two dozen.

Another area that had long been of concern to me was our Old Master drawing collection. Nothing is more important to the artistic process than drawing—sometimes a preliminary sketch, other times an independent work of art. A fine and effective university museum, with aspirations to teach, must have a collection of Old Master drawings. Janos Scholz counseled me that it was too late to form one, and he was right. We could accomplish little even if we directed our entire, embarrassingly low, annual acquisitions budget to the purchase of Old Master drawings. However, Janos also taught me to dream, think big.

I, along with so many of his students, never forgot Janos’ inspirational advice, admittedly given with gusto and theatrics. What Janos and I could never have anticipated was the arrival of Jack Reilly ‘63 on the scene. I met Reilly during one of Notre Dame’s “Fly IN” weekends and was immediately impressed with his enthusiasm for art and the Snite Museum. Reilly initially expressed interest in American paintings. He had been deeply moved by paintings by “The Eight” and other American masters at the National Gallery. We met in New York and visited several galleries specializing in American art. After we saw a lovely, small canvas by William Merritt Chase priced at $600,000, it was clear that if Reilly was going to be a serious collector it would have to be in some other area. By the 1980s most university museums were priced out of the market. American paintings of quality were prohibitively expensive.

Disappointed but not deterred, we walked a few blocks to the Shepherd Gallery on Madison Avenue. Spiro had arranged for Jack to see a collection of 65 fine Old Master drawings, assembled and refined by the distinguished scholar John Minor Wisdom. On that day, a dream came true. Jack acquired the collection and began a partnership with Spiro (now the Reilly Curator of European Art). Over the next 20 years, the two accomplished the unbelievable—the creation of a serious, high-quality collection of Old Master drawings, today the envy of many university museums. In an act of uncommon munificence, agreement between Reilly and Spiro meant the drawings would be shipped immediately to Notre Dame. Since 1986, more than 475 drawings by some of the great masters of European and American art have been added to the collection.

Rembrandt

While my 25 years in the Snite coincides with the emergence of Notre Same alumni as major contributors to the museum’s collections and programs, in 1992, on the occasion of the University’s sesquicentennial celebration, a quiet couple from Elkhart, Indiana, made a decision that was to again make an incredible difference. Alfrieda and Jack Feddersen, holding degrees from five other institutions of higher education, donated 72 Old and New Testament etchings by the Dutch master Rembrandt. The Feddersens, in a thoughtful move, transferred title to Notre Dame, but with certain restrictions. The collection had to be shown in its entirety once every three years, and at least five works had to be shown the other two years. The Feddersens were safeguarding against a practice that occurs all too often in the museum world. Collections are donated and received with enthusiasm, only to fall out of favor with succeeding administrations and/or curatorial staffs. All too often, fine collections are sentenced to dark vaults or languish in solandar boxes (storage containers for works on paper).

Like so many of the museum’s benefactors, Milly and Fritz Kaeser were not alumni nor had they ever attended a Notre Dame football game. They devoted the last years of their lives to Notre Dame because of the love for Hesburgh and for Ivan Mestrovic, the famed Croation sculptor whom the president and Father Lauck brought to Notre Dame in 1955. The Kaesers began a trend to honor Mestrovic by endowing the Distinguished Sculptor-in-Residences’s studio, as well as creating an endowment for liturgical art.

Another couple, Jeannie and Russell (Pete) C. Ashbaugh, class of 1948, had displayed their passion for Mestrovic’s sculpture. In 1974, they acquired _The Ashbaugh Madonna _for Notre Dame, an important early work by the “Maestro” fashioned from French walnut. After the museum renovated Mestrovic’s studio and installed his work in 1980, Jeannie and Pete volunteered to provide funds to pay for the Mestrovic Family Collection. Mestrovic’s wife, Olga, died in 1984, and Father Hesburgh authorized me to aquire a collection of some 298 sculptures, paintings, drawings and lithographs.

While I outlined a plan for reimbursement to pay for the Mestrovic Family Collection, I was surprised when Jeannie and Pete volunteered to cover the cost of the acquisition and care of the collection. A few years later, they made it possible to acquire the sculptor’s 1922 marble, My Mother. Bud Swinson soon joined the team and purchased Mestrovic’s 1917 marble, Mother and Child, another key work for the Maestro, created while he was a member of Vienna Secession movement. Today, no museum outside of Croatia has a more extensive collection of Mestrovic’s works.

It wasn’t uncommon for a curator to come to me after securing the right of first refusal on an important work of art. Our acquisitions fund was usually depleted, preventing us from making major acquisitions. Consequently, I would turn to the University for an interest-free loan. The museum was often advanced substantial sums so we could acquire works important to the growth of our collections. All that was required from the museum director was the assurance reimbursement was forthcoming.

Milly Kaeser’s love for Notre Dame and her philanthropy extended beyond Ivan Mestrovic. “Fritzi” (as Milly liked to call her husband) was also a fine photographer. During his lifetime, he donated several hundred photographs to Notre Dame. He thought he had presented a complete set of his works to the University. However, he had overlooked a 1977 photo session in Abiquiu, New Mexico—with Georgia O’Keeffe!

After he died in 1990, Milly was deeply concerned with what to do with her “beloved Fritzi’s” photographs. We carefully examined the collection, discussing each image. When I told Milly that we would welcome the opportunity to become custodian of his _oeuvre, _she extended her hands in an attitude of prayer and thanked God for the decision we had made. Milly also decided to establish an endowment for photography, thus assuring in this critical area that curator Steven Moriarty would be able to create collections of American photographs to complement the Janos Scholz Collection of European Photographs.

The ethnograhics collection

Another area the museum takes special pride in is its ethnographics collection. Douglas Bradley, class of 1971, recently celebrated his 25th year with the Snite. Starting with a skeletal collection of average-quality works, Bradley created a remarkable collection of Pre-Classic Pre-Columbian art, with special emphasis on Olmec art that is unique and outstanding. There are those who claim that it is rivaled only by museums in Mexico.

Growth of the permanent collections of Pre-Columbian, African and Native American art, like virtually every area in the Snite, has been through the munificence of many. Bradley developed a large base of support; the names Alsdorf, Leighton, Joralemon, Doran, Lake, Gallagher, McDonough, Griffin, Rodrieguez, Uhruh and a host of others figured prominently in the collection’s spectacular growth.

One of the principle families to support the museum’s Pre-Colombian collections was Jim and Marilynn Alsdorf. While neither were Notre Dame alumni, they did meet at a Northwestern/Notre Dame football game. For more than 30 years, they donated to practically every area of the museum’s collections. Annually, the called and invited the team—Lauck, Spiro, Bradley and myself—to their residence in Winnetka. During the first years we showed up in my 1971 Olds Vista Cruiser, that is until it had more than 100,000 miles on it, and Jim asked us to park it behind rather than in the front drive of their home. After a glass of wine, we would sit down for a fine meal and conversation about art. Surrounded by incredible art—oils by Picasso, Braque, de Chirico, Debuffet, Modigliani, sculptures by Rodin and Giacometti, Nottingham alabasters, Marie Antoinette artifacts, Tiepolo drawings, and Teotihuacan fresco panels, eating was the furthest thing from our minds. Always we wondered what the Alsdorfs would donate that year. Which curator would be the happiest? Following lunch, Jim would make the grand presentation—an Embriacchi triptych in bone, Giacometti’s portraits of the Alsdorfs, a Mayan stele and so on. We were never disappointed. The Alsdorfs had studied our collections, knew our needs and acknowledged the passions of the curators.

Building a great collection for Notre Dame can be likened to putting together a great jigsaw puzzle. While you may not have all the pieces, your appetite is such that you continue the search to complete the picture. C. Richard Hilker ‘49 became an important piece to our puzzle when I first met him in the mid-90s. The director of the Sansom Foundation wasn’t the first to recognize and express the weakness of the University’s American collection. Under normal circumstances, I could have felt a high degree of frustration. However, Hilker followed up his honest criticism by approving the gift of nearly 100 oils, watercolors, drawings and sketchbooks by the Ashcan artist William Glackens—including a pivotal work in the artist’s colorful and important career, The Artist’s Wife and Son_. This gift raised the quality of the collection another level and, equally important, it encouraged others to give important works to the Snite’s collections. It also illustrated one of my favorite expressions “quality begets quality.”

Benefactors are most interested in giving to successful rather than to floundering programs. In the museum profession, the level of quality of gifts as well as exhibitions ultimately depends on the museum’s reputation. Throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century, the collections have flourished with the addition of key examples by some of America’s finest—Maurice Prendergast, Joseph Stella, Rawlston Crawford, Milton Avery, Fairfield Porter, Phillip Pearlstein, Neil Welliver, Sean Scully and Peter Voulkos, among others.

Narrowing the gaps

When I first started working at Notre Dame, our philosophy was to fill gaps _in the collections while maintaining catholic tastes. We also learned from the Alsdorfs, who had a similar philosophy, that there was an even more important consideration when building a collection. During one of our annual visits, Spiro asked Marilynn what was their chief criteria when forming their catholic collection? She responded firmly: “I should hope quality!”

Our philosophy of filling the gaps changed in later years when I realized that even The Metropolitan Museum of Art with its collection of 3 million plus could not achieve that goal. Rather, all museums must subscribe to the philosophy of narrowing the gaps. The most efficient way of accomplishing this is through judicious purchases. The Snite has been fortunate to have created endowments early in its history. This, with some generous cash gifts, has enabled the curatorial staff to be selective, to propose and acquire objects that most effectively narrow the gaps in those areas that seem most relevant to the museum’s mission.

We also learned that an endowment, no matter what size, can be an effective tool in narrowing the gaps. The corpus of the Travis Endowment for Decorative Arts began as a $25,000 commitment; the Beardsley Endowment for Twentieth Century Art, $250,000; the Humana Endowment for American Art, $1 million. Through judicious investing and, I suspect, a little luck, each of these endowments, as well as the several other endowments bearing benefactors’ names and the collections they support, have experienced dramatic growth through the University’s wise investment program. Decorative arts became one of the Snite’s most significant collections. With Father Lauck’s early acquisitions, both through gifts and purchases (his acquisition budget to 1974 was a paltry, almost embarrassing, $5,000 annually), the Beardsley and Humana Endowments for 20th century art, with a concentration on America, now meets the requirements and expectations of the Notre Dame student body.

From 1980 to 2005, the Snite achieved national prominence. For years, “surprise” was the most common response when visitors first experienced the Snite. Another favorite phrase was “the best kept secret,” probably because our budget didn’t have a line item for publicity.

Our success is due, in no small part, to a large group of extraordinary benefactors, a talented and tenured staff, and a supportive administration. The atmosphere at the University encourages and supports those who dream. How can we improve the quality of the Notre Dame experience and make life richer for our students? The answer is found in the Snite Museum of Art, as the unique recipe for success continues under Chuck Loving’s directorship, and, will, I hope, continue in perpetuity_.