Editor's Note: This piece is part of "12 Days of Classics," a holiday series drawn from the magazine's archives and published at magazine.nd.edu from Saturday, December 22, 2018, to Wednesday, January 2, 2019. Merry Christmas!

He remembers thinking it was kind of funny, the way the young man knelt there, perfectly still, snow piling up on his shoulders and along the empty kneelers to his right and left.

Funny, and yet deeply moving, how the large, wet flakes lilted down into the Grotto while this student, his hood, coat and backpack turning white on a Sunday afternoon in December — the day before final exams and Christmas just two weeks away — remained absorbed in prayer.

How many thousands of Notre Dame students have needed a quiet moment in the Grotto to pray like that? How many times since the winter of his own freshman year had he sought the comfort of the Blessed Mother while kneeling in that same spot?

The scene touched Bobby Kloska’s heart, so he pulled out his iPhone to take a picture. He stepped a few feet to his left to better compose the shot. Then he tapped the screen — and his phone snapped off.

It was strange, the phone shutting down like that, with the battery at 42 percent and the weather barely cold enough for snow. Kloska ’90 headed home to recharge it and get ready for the week, forgetting about the student, the moment, the missed opportunity, for a few hours.

Smartphones are unpredictable. So was the sharp turn Kloska’s life was about to take.

That evening when he sat down to clear his storage and give his battery a break, he opened the photo app on his phone and remembered the picture he’d tried to take that afternoon. It was there, all of it: the student, the blue-sashed statue of Mary, the snow-covered stones, the basilica bell tower he’d paused long enough to work into the frame — and a big white splotch that appeared to be floating above the student’s head.

Kloska’s first thought was that the glare, glitch or whatever it was had ruined a shareable photo. Then he looked closer. He saw what he thought was Mary, in profile, holding a baby.

Up high. Close to her face.

The way a mother would in the cold.

Those who know Kloska well could have told you what the longtime blogger would do next. Sitting in the dining room of his home two blocks south of campus, he posted the picture on his Facebook page. He said nothing about Mary or Jesus, miracles or apparitions, just noted the “strange vertical ‘cloud’” hovering above the student.

Photo by Bobby Kloska '90

Photo by Bobby Kloska '90

“I’m not sure what to make of it, but it sure got my attention tonight,” he wrote in the public post. “Good night.”

While he slept, comments began rolling in and “shares” by the dozens were circulating the image into Facebook feeds far and wide, wonder snowballing in their wake. Before long, no surprise, a few cynics weighed in. “We see whatever our brains put together, simply said,” one wrote.

The overwhelming response, though, was one of awe and hope. Kloska sent the photo to Notre Dame classmates, who responded with admissions of their spontaneous tears. Strangers, too, said the picture was awakening their faith. It had made them weep. He hadn’t expected that.

All that week, Kloska kept quiet about the photo, turning his attention back to his work, his family, ongoing struggles with his health — all regular topics on his Facebook page. As Christmas approached, he replied privately to the constant questions he was receiving about the Grotto photo. He feared at first that if he commented on it in public, if he speculated on what had happened, what it was, he’d kill it.

But by that Friday the response was growing too large to ignore. So he decided to write a longer piece on his blog, Thoughts from the Side of the House. With it, he shared an enhanced image that a family friend had created in Photoshop, highlighting the “cloud” and darkening the background so people could see it better. He wrote about how his devotion to Mary had carried him through adulthood, and described his search for natural and technical explanations of what had appeared in the pixels inside his phone.

It wasn’t snow sliding off the rocks, he was certain of it. There’d been no wind that day, and the snow atop the Grotto’s brow was too wet to cascade down in a fluff of powder. Photographers suggested instead it was a snowflake, captured closeup during the millisecond of exposure before the camera shut off. That made more sense.

Whatever the rational explanation, the mystery remained. Was it Mary?

No, Kloska said, in an interview months later. He didn’t see anything above the student’s head that day, natural or supernatural, until he looked at the photo.

“It’s a snowflake,” he said. “It’s an incredibly providential, well-timed snowflake that has inspired tears in more people than I could even imagine to tell you.”

It wasn’t an apparition, as he’d already made clear in his blog on December 19, 2016, but maybe something like it: “Our Lady somehow arranging ordinary natural elements with astonishing timing to remind the world that she is with us, prayer is real, and everything is going to be alright.”

The minute he posted those thoughts, the Grotto photo went truly viral. Three days before Christmas, he was able to report that the post had received some 190,000 views from people in 159 countries.

The range of reactions was the same as before. Skeptics took their shots on NDNation. One woman berated Kloska for coopting another person’s prayerful encounter for his own purposes.

More typical were commentators like Rita: “This beautiful picture is giving me comfort during this most difficult time in our family.”

The photo made its way back to the student himself, who told his parents he was sure that the young man it depicted was him. His parents had both seen the Grotto photo, and his father, an old friend of Kloska’s, had already reached out to say how much the image had moved him. He’d had no idea at that time that the kid in the picture was his son.

As 2017 began, Kloska lost count of the stories deepening his conviction that the image rattling around the internet was no simple photograph.

He heard from one mother of two Notre Dame students, who, returning to Boston after a short visit and waiting for the airport bus near the campus bookstore, looked over at the Golden Dome and asked Mary to watch over her kids. When she got home, the children’s grandmother handed her a printout of Kloska’s original Facebook post.

“It was extremely consoling,” the woman wrote. “It dawned on me that your photo is of Our Lady in snow.” She enclosed a photograph she had taken of the plaque in the Grotto that marks the date of its dedication. August 5, 1896. The Feast of Our Lady of Snow — a Roman tradition connected to the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, in which the site of the church is supposed to have been chosen after snow fell on it in the summertime.

That history lesson prompted further archival research. Kloska learned that the stones used to build the Grotto were harvested from the fields of a local farmer named Peter Kintz — and that the student in his Grotto photo grew up in a subdivision carved from the old Kintz property.

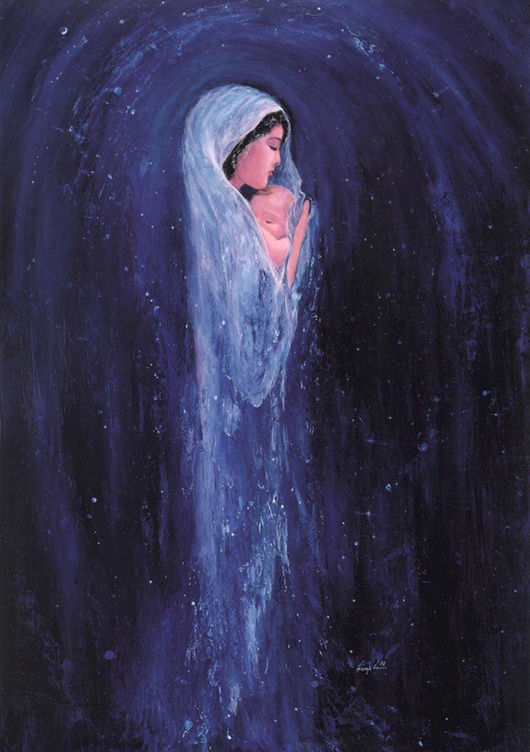

Meanwhile, a woman in Columbus, Ohio, sent Kloska the image of a poster hanging in her house. Entitled Ave Maria, the artwork depicted Mary in profile, holding her infant son close to her face. The resemblance between photo and painting was remarkable. Kloska showed it to friends, who mistakenly thought he’d commissioned a painting to go with his photograph.

After hours of web searching, he tracked down the artist. Henryka Ternier. She worked in special education in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He sent her an email showing her painting and his Grotto photo side by side. “And she wrote me back a day or two later,” he says. “‘I am the artist. I can’t believe you found me, and I can’t stop sobbing.’”

Henryka Ternier’s son died in 1986. He was 13. The details aren’t important, she says. But the grief, the denial, were overpowering. “It’s that moment where everything you are is blown to pieces,” she recalls. She could sleep only by repeating the Hail Mary.

Things got better as the years went by, and she cut a deal with “Blessed Mother.” If Mary took care of her son, Ternier would find a way to share her faith with others who seemed to need it most — people who maybe were grieving without even so much as that maternal consolation Mary had given her.

The idea was to commission a painting, an image of Mary not as she was 2,000 years ago, but as she is now, clothed in the sky, the mother of the universe, the queen of heaven and earth. Eventually she found a photo of a woman holding a child that she liked as a model. She talked to artists, but one by one they fell through, and when the last one told her in September 1997 that he couldn’t help her, “some force took over and wouldn’t let up until it was done.” She would go to the art store, buy supplies and do it herself.

She had never painted anything before.

She glued paper to foamboard, worked in acrylics. She wanted it to be professional. The stress, the self-doubt, the fear of mistakes were intense — until she discovered how to make herself an “eraser” by dipping Q-tips in denatured alcohol. Some evenings she came home from work and painted through the night, emerging the following morning as if from a trance to find hundreds of Q-tips on the floor.

Four months later, she was done. The compelling force left her and she had no desire to work on the painting, or to start another. She couldn’t even touch a paintbrush for another 15 years.

Henryka Ternier's Ave Maria

Henryka Ternier's Ave Maria

Since 1998, Ternier’s Ave Maria has hung in Kalamazoo’s cathedral. She took it to the parish church where she grew up in Poland; it spent a year in the village where her parents had met.

Far more important to her were the prints — the posters and prayer cards with the Memorare on the back that she’s printed by the thousands without a dime in payment, taking out a home equity loan to cover her costs. The price of sharing hope.

She drops them at churches whenever she travels and gave 38,000 to the Archdiocese of Chicago last year to send with its World Youth Day pilgrims to Krakow. “The total up to date is about 200,000,” she says.

All it took to connect with Bobby Kloska was one. In April, the would-be photographer and one-off painter appeared together in a five-minute interview segment for Notre Dame Day, the University’s online fundraising telethon — one more measure of the resonance the two images have had in the lives of so many people.

“If you think about it,” Kloska told Rocky Boiman ’02, “the most important woman in the history of the world, the Mother of the Redeemer, has been welcomed onto this campus, and she visits all the time. And students can take her as a mentor.

“All they have to do is invite her in.”

For Ternier, the phenomenon that began in Notre Dame’s Grotto in those tender, pensive days before Christmas 2016 is like an ode in music that conquers our hearts, evoking something too powerful to explain.

Maybe that thing in the photo was just a snowflake, hitting the light in a strange way after a confluence of circumstances too incredible to be true. But it moves people’s hearts, she says.

“And we want it to be a mystery. Do we really want the answer?”

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.