Editor’s Note: On a peaceful Saturday morning in early September I sat in my backyard, savoring the scene before me: the grass and trees and black-eyed Susans, all feeling different now — as the sunlight and scents took on an autumn mood. It reminded me of a memorable essay from years back, and that got me to conjuring a list of all-time personal favorites published in the magazine over the years. I decided to share them with you, a new one each Saturday morning until the calendar reaches 2024. Father Robert Griffin, CSC, was a beloved Notre Dame character who counseled students, said Mass for the littlest Christians and wrote weekly columns for The Observer. He was also a dear friend who was a regular contributor to this magazine. Here is a favorite of mine, a nice Christmas message. —Kerry Temple ’74

Waiting for the Lord has been the story of my life. Even when I want his attention, I choose a corner where I will be very visible, then wait to see what he has in mind. I can tell from the payoff if I’m where he wants me to be.

In my first summer of priesting in Manhattan, I was the Catholic Father on duty at Incarnation Parish when the call came: “We have a jumper threatening suicide on the George Washington Bridge. Can a priest come over to talk to this fruitcake before he takes a belly-flop on the Hudson?”

The payoff that time was that the police, using great gentleness, talked the jumper off the bridge. My prayers may have helped.

At Holy Cross Church in Manhattan, a block from Times Square, the payoff to the priest on duty is sometimes an initiation into horror. Security at the bus terminal had found a dead baby wrapped in plastic in a coin-operated locker. “Would Father like to come over and confer his church’s magic on the tiny corpse before it’s taken to the morgue?”

Neither bell, book nor candle can help the soul of a dead baby. But a priest should feel he’s never off duty as God’s stand-in. Besides, security at the Port Authority wanted a priest to dignify the small body with a corporal work of mercy.

I learned a lot about works of mercy when serving as a spear-carrier to Brother Eymard, CSC, who visited South Bend nursing homes to meet the elderly. Once a week for several years I followed him on his rounds of Wrinkle City, wearing himself out as an apostle of charity, shoring up the ruins for the senior citizens reaching their death valley days. Where, for me, was God in all this? I see in hindsight that he couldn’t have been closer.

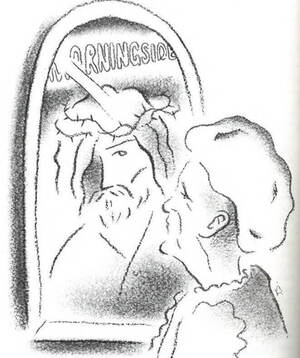

I met all kinds of people on my rounds with Eymard in the Morningside, one of South Bend’s welfare hotels which I came to know as a kingdom of the lonely God. I still have a blue cardigan sweater with the Notre Dame leprechaun that I bought as a Christmas present for Leonard, a cripple confined to a wheelchair in that hotel. Leonard died before ever seeing if the sweater fit, and it was returned to me in its Christmas wrapping.

The Leonard sweater always reminded me of how wretchedly the poor man lived, never leaving his roach-infested room except to go see the doctor. On winter nights he went to bed at 6 o’clock because he was afraid the chill in his room would be the death of him. Every time he opened the refrigerator when I was with him, I would gag on the smell from the half-eaten cans of chunky Dinty Moore stew and of peach slices slithery with juice, that he kept there as his supper.

In a way, Leonard took his own life, though not deliberately. One Christmas Eve he sent the go-fer who shopped for him to the liquor store for a pint of Old Jameson’s. After years of sobriety, he chug -a-lugged the pint as soon as he got his hands on it. His heart, amazed at the shock of firewater racing through his body, stopped beating. Suddenly Leonard was a dead man.

The last time I wore the Leonard sweater, I noticed it had a couple of buttons missing and food stains down the front of it. The shock came when I stood in front of a mirror: There, but for the grace of God, I could see Leonard — who killed himself with a last hurrah after years of living with his pilot light turned down so low it was almost out.

Brother Eymard helped me see South Bend’s shadowlands in all their color. He knew where the bodies were buried, many of them prematurely. He twisted arms to procure for his clients eyeglasses, hearing-aids, rides, Meals-on-Wheels and whatever else they needed.

One of his clients — whom I’ll call Fast Eddie — was a kingpin in South Bend’s sporting life. He used to play the host like Toots Shor in a downtown hotspot called the Club Lido. Eymard dickered for months with a government agency to pick up the tab for new dentures for Fast Eddie, who finally died and went toothless to his grave. The following week, Eymard got the green light on bringing Eddie to a dentist for a set of teeth.

The seniors could see that Eymard was not a smart-ass professional, careless about their welfare, treating them like children. With lips flecked with brown from the snuff he chewed, in the unbrushed black suit he wore as a Holy Cross brother, he was almost as shabby as some of his clients on the dole. And if you judged from his appearance, he could have been as down on his luck as the people he brought hope to.

A number of the sad people he introduced me to went to heaven so quickly I never saw them more than once. I would inquire about the English woman, cheerful as a sparrow, whom I met propped up on a pillow (I was shocked to discover she was entirely without legs). Eymard would answer: “Well, she died.”

Then I would inquire about the frail old man so tormented by body itch that his arms were tied loosely with gauze bandages to the arms of his chair to keep him from scratching himself raw. Eymard would say, “He died too.”

When I said, “Perhaps he’s better off,” Eymard would hand me fresh grief: “Remember the old man dying of cancer who told you about the charismatic priests who can lay hands on the sick and heal them with that touch? Well, he died that same evening.” The old man had been trying to find out if I was the miracle worker he prayed to meet. I had to tell him I’m not a healer. It broke my heart to see him so disappointed.

Eymard’s masterpiece in the years that I caddied for him was Stanley, who lived down the hall from Leonard at the Morningside. Until I met Stanley, I hadn’t stood close enough to old age to see what a defeat it can be. Souls bound upon a wheel of fire tend to be close-lipped and guarded about their troubles, but Stanley was too tired to stay stoic. At 87, he was a little man fierce with an anger that never left him. The anger must have tempted him to rage like Lear, but because he had emphysema, caused by being gassed in World War I, his face was the stage where his suffering took on a tragic grandeur.

Eymard went through hell and high water for Stanley. He got him an apartment and services as gratis as possible. Eymard even got Stanley free lunch. And through Stanley, Brother Eymard became a light to my conscience; I was edified by his example of love in action. In caring for Stanley, Eymard assumed a cross that merits a crown.

Stanley was a Christ-figure. As a sometime teacher of English, I have always enjoyed discovering Christ-figures in the books I read. Now, at the age of 68, I am as apt to look to life or literature as I am to the Bible.

I’ve learned that human suffering isn’t hard to explain. But how should I answer the complaints about the cosmic silence, God’s apparent indifference?

In my tour through the kingdom of the lonely God, Hemingway has become my Augustine, my Aquinas and my Cardinal Newman. His prose, by its simplicity, becomes sacramental, defined as the outward sign of an inner grace whose payoff is nada. “Our nada, who art in nada, nada be thy nada,” he once wrote in a short story. He was a half-assed Catholic of sorts. He loved rosaries and kept one hanging from his windshield mirror next to the rubber dice. When he committed suicide, the rosary was said for him at his graveside.

I read Hemingway in high school and college because I had to. I read Hemingway as a teacher because I had to — then because I wanted to. When I stopped teaching, I kept reading Hemingway, and rereading him.

Hemingway wrote simply about love, life and death. Still, when Father John O’Hara was Notre Dame’s president, he took Hemingway’s books off the library shelves, claiming Hemingway was a “bum.” Was O’Hara shocked by A Farewell to Arms, in which Hemingway wrote: “The world breaks everyone, and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure that it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.”

In an indifferent universe, death is meaningless; all that happens is that we take our turns dying. War is especially stupid. We imagine that if armies die for the sake of the abstract words, all those deaths will be meaningful. But they are not. Governments try to make war deaths a glorious sacrifice, but the promise of glory is a lie.

Hemingway’s old man of the sea, Santiago, feels a kinship stronger than death with the giant marlin he’s hooked in the Gulf of Mexico. The fish is killing him, Santiago tells himself. What does it matter, since the fish is a fine fish whom he loves like a brother. Hemingway, admiring the courage and love in Jesus when he was pushed to the wall, wrote a story about Santiago, who was courageous and loving as he faced the great trial of his life. In making his old man of the sea a Christ-figure in a world where God didn’t count much, Hemingway was complimenting Jesus.

But sometimes I don’t think Hemingway told the whole story. So I go to the Creeds to find out the whole story, or as much as we know of it. I prefer to believe the mystics who say God has a thousand faces, and the sages who say he has 9,000 names. And I read writers like Hemingway and Dostoyevsky, who tells us tales of God. Many of them are more listened to than any priest.

In my 40th year as a priest, I’ve learned that human suffering isn’t hard to explain. But how should I answer the complaints about the cosmic silence, God’s apparent indifference? One answer that was there all along — but was a long time in coming to me — surfaced when Eymard taught me to look where Christ told us we could find him: in the lives of the people waiting to be taken down from the cross. In that kingdom of the lonely God, I learned that God is lonely because so many of us fail to find him. But he is there where he wants to be found — at our side sharing pain, as he was at the side of the good thief.

Before this can make any sense, you have to believe that every story is part of the one great story of death and transfiguration, as C.S. Lewis and Tolkien have insisted. When Christian theology takes a closer look at the interrelatedness between the one and the many, Christians may start to understand that when Christ redeemed us, he empowered us to redeem one another. I have learned that as sharers of his cross we become co-redeemers with him. Sometimes unaware of what we are doing, we offer his grace, through the examples of our lives, to our peers for their redemption in Christ.

Peer redemption goes on all the time. Brother Eymard’s domesticating the wild beast in Stanley was a triumph of love. The exorcism of the demon bedeviling Stanley was nearly as miraculous as the taming of the fierce wolf of Gubbio by Saint Francis of Assisi.

I have watched students dropping out of a church that some of them never really joined and calling it irrelevant. I have grieved when good ol’ boy alums lapsed as Catholics. Coming to a bend in the road where the heavens look dark to them, they assume that the Friend and Helper has closed up shop. Describing Christianity as the light that failed, they decide to be Godlike to one another, which is lovely of them and dead on the mark, since this is what Christ wanted them to do in the first place.

Lovers, undertaking friendships and marriages that can survive hell and high water, should expect to find holes in their hands and a cross on their backs from the strain of being unselfish. Lovers who want love without the cross find that love is more difficult for those who leave Christ out of the picture.

Love that is stronger than death has its home in a church which believes that the cross is our bridge over troubled waters. Maybe it’s trite to insist on the importance of the church to the community of suffering, but wouldn’t it be lovely to believe that every sufferer’s bed is a rung on Jacob’s ladder where Christ meets his brethren upward-bound to heaven’s gate? If I were an AIDS patient, I’d like to believe that he could lead me in from the cold where I’ve been left hanging to twist slowly in the wind.

I don’t doubt for a minute that Christ is the unseen Samaritan at every AIDS hospice, using the nurses as his bright angels. Every candy-striper in Manhattan who puts a flower on the supper tray of an HIV-positive child is doing God’s work.

A New York Magazine carried a story about Sister Marietta in a Chelsea hospital where young Joe is waiting to die of AIDS. Putting her arms around him she says: “Look for your parents. They’ll be here to lead you to a happier playground.” She prays as she waits for him. Soon he tells her: “I see them, and they’re even nicer than you said they’d be.” And he dies.

Joe’s experience sheds light on the mystery that’s lingered with me since I saw my mother dying. She was blind, seeing only with her mind’s eyes, and she talked of the dead as though they were very near her. She surprised me totally when she said, “I hope the children will not bother anyone.”

“What children?” I said.

“The children,” she answered, not very helpfully. “They’ve been playing around here all morning. I hope nobody minds them being here.”

On the day of her burial the undertaker told me, “I moved the babies so they’d be nearer your mother, close by her head.” I was aware I had older siblings who had died in infancy. I wasn’t aware that they’d been buried in the family plot. When my mother spoke of the children, was she seeing the infants she had lost as a young wife? Had they come — as Joe’s parents had come — to “walk” her into God’s house?

In my very first visit to a Catholic Worker house, I watched as an infinitely patient college student tried to fit shoes on the cantankerous feet of an artful dodger from off the streets. The man had the face of a river rat and was busily masturbating under his clothes. Never noticing how this representative of Christ’s poor was distracting himself, the student wore a look of immense concentration on his face.

If he was this concerned over all God’s children having shoes in the winter, I wondered, how would he feel meeting children who have no feet? Seeing the humility with which the lad was serving this unimpressive brother of Christ, I didn’t doubt for a minute that he was a practitioner of the Gospel at its purest and simplest.

A Christian living in a world which suffers as much as ours does needs to help the other fellow pick himself up by his own bootstraps. God’s distance can leave us feeling that it’s been a long time between drinks. A father’s attentiveness should exceed that of a doctor making an occasional house call. But isn’t the long loneliness we feel when he is out of sight the very space that allows us to discover the other’s worth as a brother?

I trust in the Redeemer whom I cannot see, and in the redeeming love I cannot see, though it comes trickling down in gifts of grace. But if the only way he has of being present to us visibly is in the bonding we have as brothers in the church, should I not very visibly show myself to be my brother’s Christ?

I have this idea about God in my mind: An old grandmother in a nursing home waits for the night nurse to help her. She’s afraid of the memories that await her in the sleepless dark. If Christ would only come and let her know with a touch on her hand that he is not far away, she’d be less afraid.

Sitting up, she notices a face, tired-looking, old, as wrinkled as her own. It is, she decides, the face of her roommate in the bed across from her. Even that face is a comfort, though; if you’re religious, you see Christ in the face of your neighbor.

Then it occurs to her that the bed across from her is empty; she has no roommate. That wrinkled old face, which she prayed for the faith to see as Christ’s, is her own face reflected in a mirror.

In an age of anxiety, my mind stays busy waiting for the Lord on the peripheries, where he hangs out as the lonely God. I hope that I will be able to distinguish substance from shadows. This could happen as soon as the Lord I’m waiting for lets me catch up with him. On your death bed, I think, you have those clear days on which you can see forever.

The late Robert Griffin was University chaplain from 1974 until his retirement in the mid-1990s.