Deb Rotman and her students dig the Irish in South Bend. Literally. The Notre Dame historical anthropologist, who studies Irish immigration, conducted the department’s archaeology field school this summer at 602 N. Notre Dame Avenue, the 19th century homestead of Rose and Edward Fogarty.

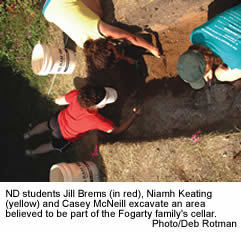

The field school, where students learn the techniques of archaeology, previously had been conducted at prehistoric Indian sites. But, Rotman says, archaeology can be a valuable tool for studying the not-so-distant past as well. Proving the point, eight students spent a week in June digging 1-meter-square holes at the corner of Notre Dame Avenue and Sorin Street.

The students meticulously sifted through the backyard dirt, searching for anything that might shed light on the Irish family who moved from Chicago to South Bend in 1865 after coming over from Ireland. The neophyte archaeologists mapped, measured, photographed and took detailed notes, because, as Rotman notes, sometimes where something is found may be as important as what is found. Following the field work, three students spent three weeks analyzing the findings in the lab. Two other students are continuing the analysis this year as independent study projects.

One of the seven excavated holes yielded a treasure trove of glass patent medicine bottles, beads from necklaces, and ceramics from tea and tableware sets. Evidence suggests the excavated area had been the cellar of the long-ago demolished Fogarty home. “The cellar was the hot spot,” Rotman says, “but I tell my students it’s not what you find but what you find out. The fact that we dug a number of holes that didn’t yield much is also significant because it tells us how the Fogartys were using the space.”

The Notre Dame Avenue site had been carefully selected by the assistant professor of anthropology. From archival records, Rotman and her students knew that Father Edward F. Sorin, CSC, founder of Notre Dame, had purchased a parcel of land south of campus to resell cheaply to workers so the University would have a nearby work force. For $25 down and the rest paid off through barter, trade or long-term credit, many Irish immigrant families took up residence in the area known as Sorinsville. Scanning the 1880 and 1900 censuses, Rotman discovered the Fogartys were once such a family.

The property now contains four houses, three facing Notre Dame Avenue and one on Sorin Street. Archival records indicate the original property was subdivided, with the second house going to the eldest daughter, Catherine, when she got married in 1885. Another house later was built for her eldest son. Those two houses still exist, north of a green-roofed house on the corner that stands where the original Fogarty home existed. A fourth house facing Sorin Street was a rental property owned by the family. Most of the dig was conducted between the Sorin-facing place and the newer green-roofed house.

The saga of the South Bend Fogartys appears to be the quintessential American dream tale of upward mobility. The senior Edward was a bricklayer from Ireland. His son, Edward Jr., was mayor of South Bend from 1902 to 1910. He subsequently became the warden of the Indiana penitentiary at Michigan City and was renowned for his work in prison reform. The eldest daughter’s son, Edward Keller, went on to become the recorder of Saint Joseph County.

In August, Rotman also took two students—senior Laura Plis and junior Lourdes Long—with her to Ireland to look at the other side of the Irish immigrant story. The anthropologist and the students spent a week in the village of Clifton in western Ireland near Connemara, interviewing families whose ancestors had emigrated to Boston and Chicago. Between 1815 and 1865, 2 million Irish left Ireland for America.

“I always describe historical anthropology as a three-legged stool,” Rotman says. “Archaeology is one leg and oral history and archival work are the other two. Census data gives us the history of a site; oral history offers personal experience of a place; and archaeology tells us about the material objects left behind, offering clues to how the people lived. They all combine for this marvelous tapestry of history.”

Each of the field school students also worked on a related project. For instance, Niamh (pronounced “neave”) Keating, an exchange student from University College Dublin, was particularly interested in the glass bottles recovered at the Notre Dame Avenue site. Records indicate that Edward Fogarty Jr. had been president of the South Bend chapter of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, an organization advocating temperance. Therefore Keating was interested in knowing whether any of the recovered bottles were for alcoholic beverages. Happily, the archaeological evidence was consistent with the archival record. There was no scandal.

Rotman intends to continue working with students at the Fogarty site next summer. In the future, she also hopes to examine a neighborhood west of downtown South Bend, near Saint Patrick’s Church, where Irish immigrants were more likely to work in factories than at Notre Dame. “We want to excavate houses in both these neighborhoods to get a good cross section of the Irish immigrant experience in South Bend.”