In the busy classroom hub DeBartolo Hall, among the students milling around from class to class, one will also find President Emeritus Rev. Edward “Monk” Malloy, CSC, ’63, ’67M.A., ’69M.A. His office is situated at the end of the third-floor hall, and can often be found with an open door.

Rev. Edward "Monk" Malloy teaching his USEM course in 2009. Photo by Matt Cashore '94

Rev. Edward "Monk" Malloy teaching his USEM course in 2009. Photo by Matt Cashore '94

Even though his tenure as president ended in 2005, Malloy maintains a strong presence on campus, working near the students in DeBart and living with them as a priest-in-residence in Sorin Hall. But a select group of 18 first-year students each semester also knows him as their professor. They meet for two and a half hours on Sunday nights to take “Biography and Autobiography: One’s Life Story,” Malloy’s famous University Seminar (USEM).

“Wait, the Father Malloy?” first-year student-athlete Maryclare Leonard asked her advisor when she suggested the class. Yes, that Father Malloy.

Malloy began teaching an early version of the class, focused on multicultural fiction and movies, after his first year as president of Notre Dame. He continued for the remaining 17 years in office, took a year off while on sabbatical, then resumed instruction of the class as president emeritus. Do the math, and that makes about three decades. “These things just happen to you and you just keep moving along, and next thing you know you have a number of years behind you,” Malloy says.

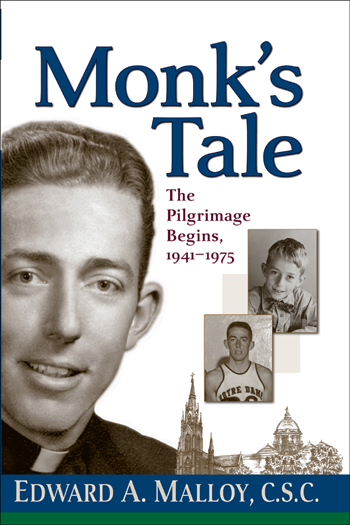

Writing his own three-volume memoir, Monk’s Tale, inspired him to change the seminar’s focus to biographies and autobiographies. Over the course of the semester, students read eight books and watch two movies that reflect different parts of the world, cultures and experiences, writing papers on them each week. The syllabus changes year to year, but reoccurring titles include Left to Tell, about the Rwandan Holocaust, and What Though the Odds by Haley Scott DeMaria ’95, who was in the women’s swim team accident in 1992. “I was never bored reading the books,” Leonard says. “You wanted to get away from your other homework to read them.”

This semester, Malloy assigned a volume of his own autobiography for the first time. Leonard says she liked learning more from the book (Volume I, The Pilgrimage Begins) about the early life experiences that made her teacher into the president, priest and professor he later became, but Malloy insists the jury’s still out on whether he’ll keep it on the syllabus.

“I’ll have to read the papers,” he says with a laugh.

The former president enjoys biographies as a reader, but he also finds that these personal stories of humanity breed excellent discussion.

“They’re ways of taking up all the great issues. I don’t just restrict myself to what’s in the book, or in the movie,” he says. “We talk about male and female, race, ethnicity, good and evil, issues like immigration, who should get admitted to Notre Dame, family life. It just depends on what the particular book or movie is.”

Malloy particularly loves having these discussions with first-year students. “I deliberately chose many years ago to teach first-year undergrads,” he says. The class, like all the small, writing-heavy courses that fit the first-year USEM requirement, is designed to expose students to the core values of a Notre Dame education early on in their college experience — with the help of a professor who might know a thing or two about the subject.

“Inevitably we talk about the big issues that anybody coming to college ought to start thinking about,” Malloy says. “And when they get flabbergasted when I keep pushing them, I say, ‘Well, this is why you go to college, so you can start thinking about these things.’”

He hopes the class helps first-year students improve their writing and feel more confident sharing their opinion when discussing important issues, but also wants to instill in them “the capacity to be more empathetic about people who have different backgrounds and cultural histories than they do.”

Despite his celebrity on campus, Malloy maintains he’s not the highlight of the class. One of the first things he said when I walked into his office? “It’s really the students that make the class what it is.”

Malloy's own autobiography appeared on his syllabus for the first time this semester.

Malloy's own autobiography appeared on his syllabus for the first time this semester.

For Kerrianne Conroy, a senior who took the class in her first semester at Notre Dame, the initial appeal was taking a class with Father Malloy, but she agrees the group of students also made it memorable. “The experience of being able to say you took a class with the president emeritus is really interesting,” Conroy says. “And the people in the class make it as well…it’s a bunch of interesting people that I don’t think I would’ve met otherwise.”

Father Malloy purposefully requests a diverse group of first-year students so that varying viewpoints, cultures and experiences can be brought to discussions and students have the chance to meet people different from themselves.

Male students. Female students. International students. Blind students. Student-athletes. Wheelchair-bound students. Deaf students. He’s had all of the above, and more.

But teaching the class gives him a chance to see beyond the surface of those general labels, through discussion of the weekly texts, but also in writing. For the final assignment of the course, students write their own autobiographies, a private project between instructor and student.

“Maybe that’s why they tell me so many things that I probably wouldn’t’ve told my teacher when I was their age,” Malloy says. Besides reading their autobiographies, which have varied in length from the minimum seven pages to the longest he’s received, 89 pages, he schedules one-on-one sessions with each student. “They’re way more open than I would ever expect. I don’t ask them to bare their soul to me, but some of them do, and I honor that.”

Conroy remembers her first meeting with Malloy in his Sorin apartment.

“He started the conversation with kind of ‘What do you think about the class?’ and then transitioned it to talking about your Notre Dame experience, why you chose Notre Dame, how you’re adjusting,” Conroy says. “Having that conversation with the former president is an experience a lot of freshmen don’t have. It set the class apart for me and showed that he cared.”

When Leonard met with him, she was similarly impressed with Father Malloy, and with the “Beauty and the Beast library” in his apartment. “I feel extremely honored to take a class with Father Malloy,” Leonard says. “He’s such an interesting man and there’s so many things that he’s done and people that he’s met.”

Establishing that relationship helps students trust Malloy with their personal stories. Then the prompt sets them free to share: “Tell me about yourself.”

- Cool Classes

- Irish-American Tap Dance

- One's Life Story

- American Political Journalism

- Summer Abroad

- Culture, Conflict, and Commemoration

- Moreau First-Year Experience

- Beginning Furniture

- The Chemistry of Fermentation

- Rethinking Crime and Justice

- Playing Shakespeare

- The Arts of Asia

“I’ve had students who have extraordinary stories to tell,” Malloy says. “Anything you can think about, except murder, I’ve probably had in the human condition.”

He lists off proof of that: “I’ve had students who won national awards in high school. I had a student who’d written three novels before he came to class. I had the daughter of the president of a country. I’ve had sons and daughters of millionaires and I’ve had people whose parents were pickers of the grape vines and maids and janitors. I’ve had students who’ve had to struggle with life-threatening diseases. I’ve had students who had certain kinds of limitations physically. I had a student one time who before she came here was in a car accident, and her father was killed…I’ve had students struggling with bulimia and eating disorders. I’ve had famous athletes. Student body president. People who won big awards when they graduated.”

Despite how impressive Father Malloy is and how fascinating the students clearly are, the class is really an exchange between the two. Even after the semester ends, he maintains relationships with each class, meeting up with them at Legends every year.

If anybody is worried about the class being unavailable in the future, don’t be.

“I’ll be 77 in May, another month, and I guess I could’ve retired a number of years ago,” Monk says, “but I didn’t and I hope I can continue teaching for the foreseeable future.”

Abigail Piper is an intern at this magazine.