One by one, the imposing metal doors whirred to life, slid open, then clicked shut behind him. Opening . . . then closing. Opening . . . then closing. Twenty doors. The process seemed to go on forever.

With each step, Drew Haase was moving farther away from life as he knew it and inching closer to the innermost core of Virginia’s death row.

He’d already been processed, questioned, patted down and thoroughly searched. Guards eyed him carefully as he made his way past the exercise yards amid the curious, hardened stares of inmates to the concrete slab that housed the cells of the state’s condemned prisoners.

What on earth was a nice guy from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, doing there?

“It was a very nontraditional Notre Dame experience for sure,” Haase says. “I had never been to a jail or anything like that, and now I was going to what they call a super-max facility.”

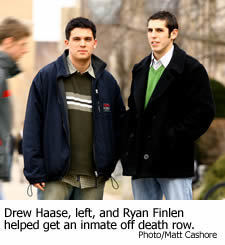

A senior majoring in political science and philosophy, Haase found himself on the business side of those prison doors last fall through his participation in Notre Dame’s Washington Program, which takes students to the nation’s capital for coursework and extensive internships in a variety of political and cultural fields. He’s one of some 40 undergraduates who, over the course of five-and-a-half years, opted to work for the Washington law firm that handled the post-conviction case of death row inmate Robin Lovitt, sentenced in 1999 to die for murdering a man with a pair of scissors.

Program director Tom Kellenberg initiated the collaboration by contacting the firm’s managing partner, who happens to be a Notre Dame alum. The students “interviewed witnesses and jurors, monitored news reports and drafted various statements,” he says. “Later they worked on legal issues, actually doing research on evidence destruction and DNA testing, as well as Virginia’s death penalty system and problems with Lovitt’s original trial.”

Haase was one of four students working with attorneys on the case when their efforts culminated in Lovitt receiving clemency from then Govenor Mark R. Warner. The Virginia governor, who was uneasy about the destruction of DNA evidence, commuted Lovitt’s death sentence to life in prison without parole.

For senior Ryan Finlen, who also was on board that fateful semester, the gravity of the experience remains. “In a small way, I helped get a guy off death row.”

And he couldn’t have done that in a classroom.

A University priority

Exactly the point of engaging undergraduates in research, according to University leaders, who are making it a top priority to get more students involved. The latest figures indicate roughly 10 percent of Notre Dame undergraduates are participating in research for academic credit. Numbers compiled by the Provost’s Office reflect a slight increase between the 2004 and 2005 fall semesters, from around 850 to just over 900 students, which is a hopeful start, according to Dennis Jacobs, vice president and associate provost.

“We have a growing enterprise on this campus,” he says. “As a research university, we have opportunities to offer a very distinctive kind of educational experience to our undergraduates. More specifically, as a Catholic research university we do, and we ought to take full advantage of what those opportunities are.”

Jacobs says it’s time to shed some light on the serious research students are conducting before collecting their diplomas. His definition of research? Students “independently studying and pursuing a line of inquiry at the frontier of a discipline.” In other words, making their own discoveries.

“We want our students to be creators of knowledge and not just consumers of knowledge,” he says. “Students say their studies come to life when they are pursuing a question that’s their own and not something that was laid out in a textbook or presented by a faculty member, but something that they are truly engaged in and interested in and want to understand.”

Cultivating intellectual curiosity is hardly a new concept in higher education, even on the undergraduate level. What is emerging as a relatively new trend, however, is the big push for such efforts at Notre Dame and elsewhere.

In fact, in his September 2005 inaugural address, Father John Jenkins, CSC, laid out his expectation that participation in this type of experiential learning should “double, and double again,” and that “students should stand on the edge of what is known and push forward into the unknown.”

Many academics cite as a main catalyst for the movement the 1998 release of a national study known as the Boyer Report that urged universities to “make research-based learning the standard.” Not everyone warmed up to the idea right away, however, according to Mark Roche, dean of the College of Arts and Letters.

“I have spoken with peers at other universities who have had a difficult time getting some of their most senior scholars to really work with undergrads in research,” Roche says. “That is not a problem at Notre Dame because we’ve always had this culture and ethos of investing in student learning, and we’ve never given that up even as we’ve added the research component.”

Roche doesn’t have to look far for an example of how the University is embracing the idea. His college boasts what many consider the crown jewel of Notre Dame’s endeavors in the area—the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP), which provides individual and team grants and summer fellowships for student-initiated projects. Topics run the gamut—Panamanian ecotourism, Indian child serfs, mating habits of cotton-top tamarin monkeys and Irish music are a few recent highlights.

Student projects

Senior Anna Nussbaum was one of some 20 students who embarked on UROP projects last summer. With her grant she researched and wrote The Primrose Path, a play she created as an alternative to the controversial The Vagina Monologues, performances of which have stirred great debate on campus in recent years.

Nussbaum’s research involved interviews with more than 80 people about sexuality and faith, “Everyone from my parish priest to ex-boyfriends to a transsexual I met at a movie theater,” she says. The Primrose Path made its campus debut in February.

“I don’t think I would have had the courage to write a play unless I had that kind of structure and academic support,” says Nussbaum, who now plans to pursue writing as a career.

Senior Peter Quaranto used his UROP grant to investigate and illuminate the plight of child soldiers in war-torn Uganda.

“I was in shock, blown away by how victimized these children were,” he recalls. “While I was conducting interviews, doing research and experiencing the war-torn area, I sensed a need for international advocacy to bring the situation to the attention of the world community.”

When Quaranto returned to Notre Dame, he and another student created just such a vehicle, the Uganda Conflict Action Network, an advocacy and lobbying organization that works toward an end to the country’s nearly two-decades old war.

Freedom to blaze their own trails and topics that inspire creativity are major draws of UROP, according to Gretchen Reydams-Schils, director of the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, which facilitates the program. “It’s very much about empowering undergraduates as responsible, intellectual, moral agents,” she says.

UROP’s popularity has skyrocketed since its inception in 1993; last academic year, 103 students participated and more than $145,000 in grants was awarded. Reydams-Schils credits the surge in large part to word-of-mouth advertising from students who are encouraging their peers to catch the research wave.

Beyond the desire to produce a more enlightened, culturally aware student, Notre Dame’s move toward undergraduate research also is strongly rooted in the desire for more students to pursue doctoral degrees, to put a “Notre Dame stamp on higher education,” say Roche, who laments a “more modest number” of students going on for their Ph.D.s here than at other institutions.

“Teaching is a noble profession in a way that our undergraduates tend to underestimate,” he says. “We think our students have the right moral formation, and they should be faculty members at other universities. It adds to the prestige and standing of Notre Dame.”

Administrators say the benefits don’t stop there. In theory, undergrads who participate in research also are more likely and stronger candidates for prestigious fellowships, such as the Fulbright. Leaders also see research opportunities as recruiting tools for bright, inquisitive potential students.

UROP is a prime example of what many consider a new wave of creativity-driven research, largely in the humanities—a step away from the more traditional, scientific discoveries that might take place in a lab. That, however, does not mean those enterprises are anything less than flourishing at Notre Dame.

Mitchell Wayne, associate dean of the College of Science, says he was thrilled to hear Jenkins’ call to step up undergraduate research. The college already offers research opportunities to “any student who wants one,” he says, and the majority of traditional majors do participate on some level, with enthusiastic support from the faculty.

“Many of us got our start that way, so we’re more than happy to help our students get their start as well,” Wayne says, adding that the college will seek ways to maximize its efforts in light of the directive from the top.

Mendoza’s challenge

While the University’s aim is to promote undergraduate research in all academic disciplines, the Mendoza College of Business does present a particular challenge. With no Ph.D. program and the overwhelming majority of students dead-set on professional careers and maybe an MBA, Associate Dean William Nichols says the college faces substantial obstacles in furthering the administration’s agenda.

“If motivation for undergraduate research is to improve critical thinking and discovery skills, we do that,” he says. “But if the motivation is to get students to go on to pursue an academic career, we don’t do that as much.”

Mendoza is far from alone in this regard among business colleges, and Nichols predicts a “huge shortfall” of faculty in business in coming years as a result.

A handful of Mendoza faculty members, including Elizabeth Moore, an associate marketing professor, do engage undergraduates in hands-on research. Her experiences, including co-authoring a paper with one student, have been largely positive, she says, but the complexity of many topics brings limitations.

“If I were doing a quantitative model, for example, I don’t know how much undergraduates could do,” Moore says. “But there are pieces of the project that I can give to them, and they’ll do a terrific job.”

The research movement, however, does raise eyebrows among some Notre Dame constituents, who have long questioned the compatibility of the University’s quest to become a top research institution and its mission to educate undergraduates. Jacobs, however, says the experience of undergraduate research itself is the strongest argument to counter that point.

“For the hundreds and hundreds of students who are engaged in this, I think we’ll all agree that it wouldn’t have happened if Notre Dame didn’t have serious research taking place, if it weren’t a part of our mission and our campus life,” he says.

Roche also points out that Teacher and Course Evaluations are higher now than 10 years ago, before Notre Dame began its major drive into research. “That’s clear, empirical evidence that, at least from the students’ perspective, the quality of teaching has not been diminished, it’s improved,” he says.

Notre Dame still has a ways to go before it can join the ranks of leading institutions such as Princeton, which requires every student to complete a research project for a senior thesis, and Duke, which has a research course requirement built into its curriculum. But campus leaders believe Notre Dame is poised to become a serious player.

The first step in that direction consists largely of exploring ways to best measure, showcase and boost student involvement, with a short-term goal of doubling the current level of participation to around 20 percent. Jacobs’ office is developing a student survey to get a handle on exactly what projects are taking place. A new University website (undergradresearch.nd.edu) is already on-line, listing opportunities for internships and fellowships by academic department. A web-based repository to display the end results of undergraduate projects—from papers and presentations to artwork, film and video—is set to launch this spring, the same time an on-campus Research and Creativity Fair also is planned.

For students who have taken the research path, the appreciation of the experience is invariably similar, whether their projects took them to the library, the zoo, Africa or maximum security.

“It was the most hands-on experience that anyone’s ever offered,” says Ryan Finlen of his death-case work. “It’s amazing the opportunities that were afforded me through Notre Dame.”

*Julie Flory is an assistant director in the Notre Dame Office of News and Information.