In the back room of The California Clipper Lounge, the rumble of Chicago traffic crept inside against the softly spoken word of poetry. Sheryl Luna, dark hair draped around her face, spoke sideways into a microphone a tangle of words alluding to the desert Southwest:

“And I remember that it is good to be born of dust, / born amid cardboard shanties of sweet gloom. / I remember that the bare cemetery stones / in El Paso and Juárez hold the music, and each spring / when the winds carry the dust of loss there is a howl, / a surge of something unbelievable, like death, / like the collapse of language, like the frail bones / of Mexican grandmothers singing.”

That July evening Luna finished reading “Bones,” a poem from her collection Pity the Drowned Horses, while the director of Letras Latinas, the literary program of Notre Dame’s Institute for Latino Studies (ILS), sat in the audience. The poetry collection earned Luna the first Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, an award sponsored by ILS, and was published in 2005 by the University of Notre Dame Press.

The institute’s reach, rooted in South Bend, extends beyond Luna’s reading in a shadowy city corner to Chicago’s near west suburbs; east to Washington, D.C., and west to Los Angeles. The ILS mission is as vast, reaching out to the broader Notre Dame community through literature, art and religion, education and research.

“People just assume that a program of this sort will be good for Latino students. And that’s good. We want to be relevant. And that’s why we’re here,” says ILS Director Gilberto Cárdenas ’72M.A., ’77Ph.D., an assistant provost and Julián Samora Chair in Latino studies. “But we measure ourselves on how we broaden our work and mission.”

Allert Brown-Gort, the institute’s associate director, says the rise of the Latino community in the United States is the demographic story of at least the first part of this century. That population change will alter the cultural landscape in as dramatic a way as advances in technology and global climate change.

“And people see this and are not quite sure what to think about it. Sometimes they’re afraid. Sometimes they’re hopeful,” he says, adding that institute staff members strive to be honest brokers between this rapidly growing population and the non-Latino community.

“There is a lot of opportunity there for this country,” Brown-Gort says. But the Latino and non-Latino communities, he adds, are responsible for ensuring that the opportunity isn’t squandered. As the immigrant population expands beyond the Southwest and Southeast, it needs to engage more with the societies it is joining. “At the same time, the communities that are receiving them need to understand that they are receiving a benefit,” Brown-Gort says. “They have more people who work hard—people who are basically trying to do the best for their families. People who, in a lot of ways, are giving a lot more than they get.”

The integration of Latinos and non-Latinos is a given, he says. The question is whether to let it occur naturally—which likely would be slow going—or whether to help it along.

ILS wants to help it along.

- * *

In Berwyn, Illinois, about seven miles west and south of The California Clipper Lounge, the Sears Tower is visible from main roadways on clear days. Brick bungalows line the centenarian suburb’s streets. In this community and the surrounding Chicago area, the ILS Center for Metropolitan Chicago Initiatives collaborates with local churches, nonprofit organizations and universities to conduct research and pastoral work.

Nearly a century ago in Berwyn, 150 Czech families were among the founding parishioners of Saint Mary of Celle. The face of the community has changed in recent years. Tamales and peppers bursting in bright reds and greens like Christmas lights have joined dumplings and sauerkraut on supermarket shelves. With Berwyn’s recent influx of immigrants—this time Latino, instead of European—Saint Mary of Celle now celebrates Spanish Mass every Sunday.

In 1990, about 3,500 Hispanics and Latinos lived in Berwyn, at the time about 8 percent of the village’s total population, according to U.S. Census data. By the turn of the century, the group had swelled by about 17,000, so that Hispanics and Latinos made up 38 percent of the total.

Similar changes have occurred throughout the Chicago area and the United States.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops estimated in 2002 that Hispanics comprised nearly 40 percent of U.S. Catholics, a percentage that’s since increased. ILS leaders say several congregations with rapidly growing Latino communities have asked them to visit, to initiate conversations about immigrants and their children: who they are, why they’re here, how they view the world.

“The vast majority of Americans are, you know, they’re bothered by some things because they just don’t understand. Mostly they don’t come face to face with immigrants in their day-to-day life,” Brown-Gort says. “Church, however, is like part of your house. It is one of those public-private places.”

When a congregation has been one certain way for a person’s whole life and then changes, it can stir up a lot of questions.

- * *

ILS aims to address those questions head-on through education, research and community outreach.

In South Bend, Notre Dame students have worked directly with immigrants to create a community guide to social services in the area. They produce fact sheets to aid local hospital administrators in dealing with Latino patients and offer bilingual tutoring in local parishes. A student initiative, supported by ILS, brings to campus high school students, many of whom are the children of immigrants and would be the first in their communities to attend college. The pre-college program offers students who otherwise would be initiated trial-by-fire into campus life a glimpse into the basics of survival: where to live, wash clothes and eat meals.

“A good part of what we’re doing is focused on the University’s current desire to be a good citizen in the community,” says Caroline Domingo, ILS communications director.

Research conducted from McKenna Hall bolsters community outreach and advances the institute’s academic mission. In addition to the Chicago center, ILS runs the Centers for Latino Spirituality and Culture; Migration and Border Studies; and the Study of Latino Religion.

Letras Latinas, another branch, operates out of Washington, D.C. The program has presented three poetry prizes: to Luna, Gabriel Gomez and, most recently, Paul Martínez Pompa. It partners with literary organizations to sponsor events, such as Luna’s reading in Chicago, and has an online journal. Another ILS project, to create an online directory of archives documenting the history of Latino art in the Midwest, further demonstrates its commitment to the arts.

Through these centers the institute has co-sponsored conferences on such issues as migration and theology, and partnered with the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus to host a series of roundtables about the assimilation of Latinos into metro Chicago. The institute has published research papers and studies on educational gaps in the community, home ownership, retirement planning and civic participation.

Many of these publications are available on its website, latinostudies.nd.edu/, as is a database that ILS maintains with comprehensive census information for the greater Chicago area.

Since 1999, when ILS began, Notre Dame has been the headquarters of the Inter-University Program for Latino Research, for which Cárdenas is the executive director.

The national consortium of 24 academic research centers, including the University of Texas at Austin and the Smithsonian Institution, works to advance the intellectual presence of Latinos in this country through policy-focused research. In July, Notre Dame hosted a workshop on Latino health and obesity, but the consortium’s research spans border affairs and migration, demographics, arts and culture, and Latino families.

- * *

ILS leaders hope that through the Spirit of Notre Dame campaign donors will contribute to a $15 million fund-raising goal, which would enable the institute to continue to strengthen its academic standing and create more consistent programming.

“We want research that makes a difference,” Domingo says. “We want our work to be accessible to policymakers, to interested members of the public, to people who are involved in that issue as practitioners or as recipients of whatever it is.”

“However,” Cárdenas adds, “our goal is to also be advancing the academic work as well, because in the end that’s what the University values and champions.”

A proposed center devoted to the study of Latinos in Indiana and modeled after the Chicago center would help meet that objective, ILS leaders say. So would a center for art and culture; its preliminary plans include galleries and studio space in downtown South Bend for visiting artists; an artist- and writer-in-residence program; and a fine art print house.

ILS also is looking to collaborate with the University to expand its library and research collection to attract visiting scholars and further distinguish Notre Dame as an academic destination for the study of Latinos and the Latino Catholic experience.

“It [would give] us a presence on campus and that for us, that’s the biggest issue, is to really create that presence here,” Cárdenas says. “And for people to understand that we’re not just here for Latino students and Latino faculty. That’s all fine and that goes with it, but we’re here for the entire University, and that’s how we’re trying to measure ourselves: How interested can the entire campus be in the kinds of things that we can do? How relevant can we be to advance Notre Dame’s mission throughout, not just in this little corner?”

Emily Dagostino is a writer who lives and works in Oak Park, Illinois. She can be reached at etdags22@yahoo.com

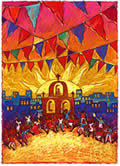

Our Community serigraph by Nery Cruz, 2002