Here is my Sophomore Literary Festival moment.

I am in the old Pay Caf, also known years ago as the Oak Room in the South Dining Hall. High ceilings, beautiful woodwork, those familiar, distinctive aromas.

I am having coffee with Barry Lopez and Edward Abbey. They are two lions of 20th century American nature writing. For prominence and message they would be considered descendants of Whitman and Thoreau; they’d be on the short list with Aldo Leopold, Wendell Berry, Annie Dillard, Edward Hoagland and John Muir as the literary shapers of America’s environmental consciousness. And I am sitting here, sipping morning coffee and listening to these giants talk about wilderness preservation and water rights, native cultures, wildlife and the role of federal government.

Sage-like even in 1983, Lopez, a 1966 Notre Dame graduate, had gained acclaim for Of Wolves and Men. He speaks quietly, thoughtfully. Abbey — always the rebel, the renegade, “the desert anarchist” — is sharper tongued, irreverent and direct. He looks like he stepped right out of the Southwest backcountry: rumply dressed, ample beard, slick hair spearing from beneath his stained and worn-out hat. He’s delightfully out of place at Collegiate Gothic Notre Dame.

Still, Abbey has published his classic beauty Desert Solitaire and his subversive The Monkey Wrench Gang, and two of his novels have been made into movies, Lonely Are the Brave and Fire on the Mountain. By the time he died in 1989, he had become an American icon.

The moment was a refreshing infusion of elan vital in my workaday world. But it would be a typical encounter in the life of the Sophomore Literary Festival, a colorful Notre Dame spring tradition launched in 1967 to bring such literary champions to South Bend, Indiana. Its run lasted more than three decades before fading out of the campus scene.

The cool thing about the Soph Lit Festival is that it was begun by students and was run by students. Students — sophomores — extended the invitations to those authors, poets and playwrights they wanted to hear from and be with. Sophomores made the travel arrangements, met the planes and escorted the writers from hotel to reading to reception. And the writers — at least in the SLF’s heyday — stuck around. They not only did readings, gave talks and made pleasant conversation at post-event receptions. They also spoke to classes, put on workshops, visited with each other and with students, attended wine parties in faculty homes and . . . hung out, usually over the course of a few days. So opportunities for morning coffee or late-night wine were there. It was a week-long festival, it was fun (with some groggy mornings-after).

Gwendolyn Brooks, Chaim Potok and Arthur Miller came my junior year. Joyce Carol Oates and Isaac Bashevis Singer came when I was a senior. Susan Sontag came in 1983, the year Lopez and Abbey were here, as did Richard Brautigan, famous for his period piece Trout Fishing in America. It was Brautigan’s final reading prior to committing suicide.

The impressive list of participants includes Edward Albee, Tom Stoppard and Jorges Luis Borges. Larry McMurtry. Ann Beattie and Margaret Atwood. Jerzy Kosinski. Allen Ginsberg and Ken Kesey came more than once.

Many of the leading poets of the late 20th century read, coached and talked shop with students and faculty alike, a list that includes Galway Kinnell, Kenneth Rexroth, Robert Bly, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Seamus Heaney, Howard Nemerov, Stephen Spender, Denise Levertov and Sam Hazo, a 1949 ND graduate. The Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz came in 1982, two years after winning the Nobel Prize for literature.

The festival also brought to campus many of the period’s most influential black voices. Claude Brown came in 1970, five years after Manchild in a Promised Land drew intense critical acclaim for its depiction of his growing up in Harlem and his take on American society. The SLF also attracted Ralph Ellison, whose The Invisible Man won him a National Book Award in 1953.

The festival’s leitmotif and cast of characters often translated into edgy, eccentric and unpredictable moments. In 1977 Tennessee Williams opened his presentation on the stage of Washington Hall by pouring himself a glass of wine and toasting Our Lady atop the Dome and then “Notre Dame’s homosexual community.”

In 1985, John Irving reportedly responded to his invitation by saying that the Catholic university may not want him; he was writing a novel that dealt with abortion. He was encouraged to come anyway. That year’s chairman, Greg Miller, told The Scholastic: “We weren’t going to deny the tradition of the literary festival or hold back an author just because he was going to read about abortion, which if you can’t do at a university, you really can’t do it anywhere.”

The SLF was clearly a product of the times, written into a chapter in the life of Notre Dame and American history when the day’s institutional, literary and intellectual currents were embraced in a freewheeling conversation. It was a reflection of the students’ creative, cultural and educational aspirations. In fact, its prime movers openly stated that one of their purposes was to dispel Notre Dame’s reputation as a mere football school.

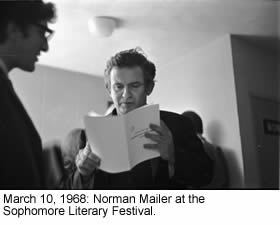

The year was 1967 and a visionary, entrepreneurial sophomore from Mississippi named J. Richard Rossie put together a conference to honor the Magnolia State’s William Faulkner. The following year John E. Mroz of Osterville, Massachusetts, created a festival celebrated in the Saturday Review and The New York Times. The 1968 lineup included the dean of literary critics Granville Hicks, who penned a post-festival feature for the Review, Norman Mailer, Ralph Ellison, Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller, William Buckley Jr. and Wright Morris, who had won two National Book awards.

Mroz had to patch together funding for the festival. He got a nice boost from Charles Sheedy, CSC, dean of the College of Arts and Letters, who admired Heller’s Catch-22. Heller said he’d come if he could get an autographed football for a family member.

The 1968 festival attracted overflow crowds and was rocked by a series of nationally historic moments. It opened March 31, the day President Lyndon Johnson announced he would not seek re-election. Before the festival ended Martin Luther King would be assassinated. In between Buckley would pepper his talks with barbs slung at presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy. The day after Buckley graced the Stepan Center stage, Kennedy appeared at the same venue, drew enthusiastic applause and replied: “This must be the warmest reception anyone has had in this auditorium since William Buckley spoke here last evening.”

Don Costello, longtime faculty member and informal festival adviser, would say of the festival’s birth years later: “Of course, it couldn’t be done. That’s the beauty of naïve sophomores. They were too naïve to know it couldn’t work.” But over its first two years alone it would bring to campus Tom Wolfe, George Plimpton, John Knowles, John Barth, Peter DeVries, Gary Snyder, Ishmael Reed and LeRoi Jones.

In time the national literary scene changed, and authors expected more for personal appearances. By the mid-1990s the festival had pretty much run its course. It was a product of the times. But what good times they were.

Kerry Temple is editor of Notre Dame Magazine.