On a sunny Sunday morning at the edge of the Adriatic, Archbishop Charles Brown ’81 and I are at an impasse. The dirt road we’ve followed for miles has narrowed into nonexistence, and our driver decides we’ll have to try a different route if we’re ever going to make it to Mass. So he jerks the car back in the opposite direction, and now we are faced with the rear end of a bus.

Its double doors swing open, and out pour 10, 20, 30 children dressed head-to-toe in the traditional garb of the Western Balkans, clutching tiny string instruments and felt hats and completely blocking our path.

The bishop laughs.

“I love Albania.”

“I love Albania” is a declaration you’ll hear a lot if you make a habit of hanging out with Archbishop Brown. So is shumë mirë, Albanian for “very good” and one of few easy phrases in the language Brown has been learning since Pope Francis appointed him apostolic nuncio to Albania in March 2017.

So, too, is the story of Francis’s trip to Albania back in September 2014.

“Pope Francis has a great love for Albania,” Brown told me more than once during my visit to the country in May. In fact, aside from Italy, Albania was the first European nation Francis visited as pope. It was one of the first nations he visited anywhere.

Why Albania? It’s close — barely 50 miles across the Adriatic from Italy’s bootheel — but Brown insists that’s not the reason his boss chose the country for an early visit. Nor did he select Albania for its robust Catholicity — the country is majority Muslim and for much of the 20th century was an officially atheist state. But as the pontiff said during his 11-hour stop in the capital, Tirana, “There is a rather beautiful characteristic of Albania, one which gives me great joy: I am referring to the peaceful coexistence and collaboration that exists among followers of different religions.”

In a world facing increasingly bitter divisions along religious lines, Albania provides a rare model of people from different faiths getting along. That interfaith harmony brought Pope Francis to Albania, and it has brought Albania to the cusp of membership in the European Union. It probably brought Archbishop Brown to Albania, too.

Before accepting this post, Brown was the Vatican’s ambassador, or nuncio, to Ireland. I overlapped with him when I spent a year in Dublin after graduation, and I happened to be back there when the news broke that he was headed east. My former pastor mentioned the reassignment over a cup of tea, and we shared a conspiratorial glance and knee-jerk response:

“How’d he get that demotion?”

All I knew about Albania at the time was that, according to the Harry Potter series, Voldemort hid out there in the 1980s after attempting to kill the Boy Who Lived. For a Vatican diplomat to be sent there from ultra-Catholic Ireland, I reasoned, some higher-up had to be displeased.

What I didn’t know was the fascinating politics of this unusual little nation in the days since He Who Must Not Be Named passed through. After half a century of communist seclusion and a couple decades of upstart democracy, Albania clawed its way to EU candidate status in 2014. By then, the country’s previous nuncio, Archbishop Ramiro Moliner Inglés, had served six years in a post typically expected to last five.

The Vatican needed a new man in Albania, and Albania needed diplomats who could help make the country’s case to a skeptical Europe.

Enter Charlie Brown.

Yes, the nuncio told me when I sheepishly asked, Charles does become Charlie around friends and family, despite the animated character who shares his name. The archbishop-diplomat’s father was Charlie Brown, too, and he held claim to the name long before Peanuts came along — Snoopy & Co. were still brand-new to American newspapers when Charles Senior graduated from Notre Dame in 1956.

The younger Charlie tried to distance himself from the comic strip a few years back, opting in many professional settings to go by his full name, Charles John Brown. But middle names don’t exist in Albanian, so, to avoid confusion, he’s had to drop the “John.” He may be on speaking terms with both living popes, but some fates can’t be avoided: “Charlie Brown” will always call to mind, well, Charlie Brown.

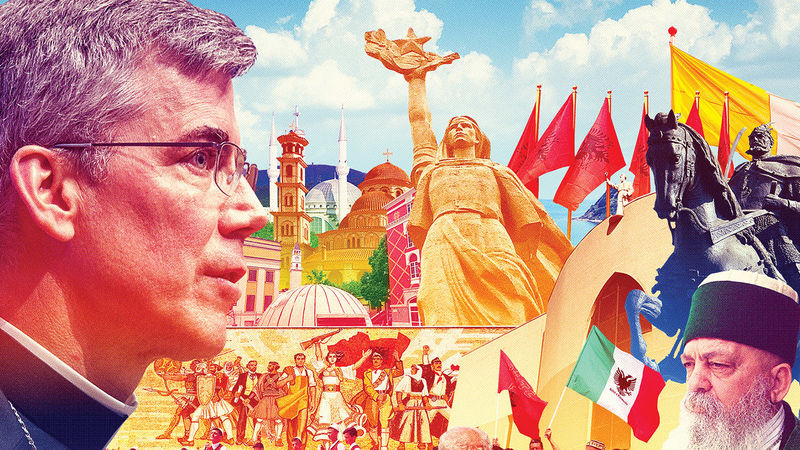

Three structures pierce the heavens above the capital: the steeple of St. Paul's Catholic Cathedral, the clock tower of the Resurrection Cathedral of the Albanian Orthodox faith, and the minaret of Et'hem Bey Mosque, one of the few houses of worship to survive Hoxha's rule.

The comic strip of Archbishop Brown’s life begins in New York City. He was born there in 1959 and spent his early years surrounded by the prominent Catholic Manhattanites that comprised his parents’ circle of friends — Dorothy Day included. The family moved upstate in 1971, and, a few years later, Charles departed for Notre Dame. He was placed in Sorin College and, fittingly for a legacy student and the eldest in a family where all six children would eventually become Domers, spent two years living in one of the most iconic rooms on campus — a third-floor Sorin turret quad.

Among his roommates was Steve Reifenberg ’81, now an associate professor of the practice in the Keough School of Global Affairs. Reifenberg remembers the archbishop as a man of many passions: a diligent history student who would launch weeks-long debates on criminal justice or modern art around the dorm, an athlete who braved snowdrifts to run laps around the lakes in winter, a deeply religious young man who organized road trips with friends to Trappist monasteries in Kentucky and Massachusetts.

“He sometimes talked about going to law school or becoming a teacher,” Reifenberg recalls, “but there was also a sense of the possibility of a religious vocation in the background.”

That possibility remained in the background for a few years after Brown’s graduation while he continued his studies at Oxford and the University of Toronto and spent a summer trekking the Himalayas. By the mid-1980s, he had heard the call to the priesthood and decided to follow it, first home to New York and then, in short order, to Rome. New York’s archbishop, Cardinal John O’Connor, wanted him to finish the doctorate in medieval studies he’d started at Toronto before coming back to teach at the seminary at Dunwoodie in Yonkers, but the Vatican had other plans. In 1994, Brown was nominated to fill an opening in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), the office that watches over Catholic teaching. His new boss? Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger.

Brown worked at the CDF for the next 17 years. In 2011, his former boss, now Pope Benedict XVI, had another job for him: nuncio. Typically, Vatican diplomats must attend the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy and spend years in low-level jobs before becoming nuncios, making Brown’s nomination straight into the diplomatic elite unusual. But under Ratzinger and his successor at the CDF, Brown was a crucial part of the team that shaped the Church’s response to the worldwide sex-abuse scandals. Ireland had been particularly hard hit by such scandals. To Ireland Charlie went.

John O’Callaghan ’86M.S., ’90M.A., ’96Ph.D., an associate professor of philosophy whom Brown befriended while on sabbatical at Notre Dame in the mid-2000s, says what’s impressive about the archbishop is not just his résumé, but his personality.

“I think he’s just a very warm person to be around,” he says. “He’s got a kind of dignity, but a dignity that isn’t off-putting.”

He recalls a story Brown told him over lunch one day about a one-on-one dinner Brown had with Benedict. Over the course of three hours, the two churchmen mostly just traded jokes.

“Here’s this guy,” O’Callaghan says, “who’s very precise, very neat, very much in self-control, but who nonetheless has this ready humor and this ability to just have a warm conversation with the pope. And I’m thinking, ‘Now you’re sitting here talking to me.’”

With his hierarchical achievements and skills with people from all walks of life, might Brown be a candidate to become the first American pope? O’Callaghan and Reifenberg have both heard friends mention the idea — and heard Brown ardently shoot it down.

Reifenberg notes that Brown has always said his plans for the future were to be faithful and obedient, “to be a good priest.” I heard the archbishop echo that sentiment in Albania.

Suspending some journalistic professionalism, I admitted to Brown that I was flabbergasted to be in the presence of someone who’s worked with Mother Teresa and Pope Francis, and who counts Pope Emeritus Benedict among his close personal friends. He disagreed that his trajectory is anything remarkable.

“Listen,” he said. “I’ll be 60 years old next year. When you’re 60 years old, you’re going to have the same experience. I mean, 25 years ago, Cardinal Ratzinger was just a cardinal. He wasn’t pope.

“What can I say,” he continued, “except that it’s been a great gift and a great grace in my life? God gives us a certain amount of time on this Earth to do something beautiful for him in response to the love he has given us. We go forward.”

The Holy See’s Albanian outpost is housed smack-dab in the center of Tirana. A few blocks from the nunciature — that’s Vaticanese for embassy — lies Tirana’s central square. The National Museum of History hems in the square on the northern end, and, on its façade, a hulking mosaic provides the plaza’s most striking landmark. A 1981 work by five local artists, The Albanians purports to represent all of Albanian history, and it mostly does — real national heroes from two millennia stand beside fictionalized symbols of modern Albania that were in favor at the time.

It is an arresting piece of art, but not exactly in a good way. The 13 Albanians shown are caught mid-march, faces set in stern national pride and arms raised as if in triumph. But most of the outstretched fists clutch swords or rifles. Some are dressed in traditional folk costume, but many are outfitted simply as workers. A blood-red Albanian flag waves behind their heads. To the modern observer, the message is obvious — and unsettlingly communist.

Until recently, so was Albania.

Following centuries of conquest by foreign powers — the Romans, the Byzantines, the Ottomans — Albania asserted its independence in 1912, but straightforward autonomy remained elusive. The nation was a monarchical principality, then a republic, then a monarchy again over the next 20-odd years. The young country was soon invaded again, by Italy in 1939 and Germany in 1943. Amid this chaos, a communist party arose.

Unlike their counterparts in the Soviet bloc, the Albanian communists had no interest in coalition. The party — the National Liberation Front — touted an independent Albania as its sole aim, and in 1944, it achieved its goal. The nation so long buffeted between warring powers had become truly a state unto itself, and its new prime minister intended to keep it that way.

Enver Hoxha instituted a regime of isolation and totalitarian violence. He alienated allies, clung to the Soviet Union (and later, when the Soviets were deemed not communist enough, to Maoist China), slaughtered his political enemies and established the Sigurimi, a secret police force known for extensive surveillance and brutal torture of suspected rebels and traitors.

He also declared Albania the world’s first atheist state. The practice of religion was outlawed and churches and mosques were seized. Members of the clergy were ordered to leave the country, and when they refused, hundreds of priests and imams were imprisoned or killed.

In the country’s 46 years of communist rule, more than 6,000 people died at the hands of the Albanian government. The country committed some of the worst human rights abuses of the era, but, by design, it remained cut off from the rest of the world. Private ownership of cars was forbidden. Every consumer good an Albanian might want, from blue jeans to televisions, had to be made in Albania. Few people were allowed in, and even fewer were allowed out.

Over the decades, Hoxha grew increasingly paranoid. Despite the country’s small footprint on the world stage, he became convinced that nuclear attack was imminent and ordered the construction of hundreds of thousands of bunkers across the 11,000-square-mile country. He died in 1985 convinced that even his closest allies were enemy spies.

Hoxha’s successor, Ramiz Alia, gradually relaxed policies and introduced reforms in step with the dissolution of Europe’s other communist governments. In 1992, Alia and his party were ousted in one of Albania’s first free elections in half a century.

Albania’s recent history is still visible in the streets of Tirana. It lives in art like the mosaic on the history museum, and it lives in the bunkers, which still appear everywhere from city parks to luxury hotel courtyards. You can see it in the stark communist architecture that Y2K-era politicians ordered repainted in sunny pinks and blues. It’s discernible in the economy — rock-bottom deals like $2 lunches are a draw for tourists but a necessity for locals, for whom 600 American dollars a month remains a respectable salary.

But the country’s ancient history is still visible, too. Albania is a place where East meets West, and that collision is evident in the Tirana skyline. Between office buildings and against the backdrop of the Accursed Mountains, three structures pierce the heavens above the capital: the steeple of St. Paul’s Catholic Cathedral, the clock tower of the Resurrection Cathedral of the Albanian Orthodox faith, and the minaret of Et’hem Bey Mosque, one of the few houses of worship to survive Hoxha’s rule.

In a city whose airport is named for Mother Teresa, an ethnic Albanian, church bells and Islamic calls to prayer are equally prominent sounds. Government functions often feature the robed national chairmen of four or five religions, from the American-educated head of the evangelicals to the green-fez-wearing “baba” of a local sect of mystic dervishes.

From the pope to the governors of the European Union, everyone seems to agree that Albanians provide an admirable model of interreligious harmony, but no one can easily explain why. There’s no reason Muslims and Christians get along so well here, it seems — it’s just in their blood.

Muslims comprise 57 percent of Albania today (compared to 10 percent who identify as Catholic), but that’s primarily a legacy of the Ottoman Empire — invading Ottomans forced most people to convert in the early 1600s. Before that, this land was as Christian as it gets: Romans indicates that Paul preached the Gospel “even unto Illyricum,” and what antiquity knew as Illyricum, modernity knows (in part) as the Balkans.

Enver Hoxha had a favorite catchphrase: “The religion of the Albanian is Albanianism.” Despite his malicious anti-faith crusades, the declaration may be a simple demographic truth. Ancient Albanian Christians weren’t Catholic zealots — they just adopted the religion of the conquering Romans. Orthodox Christianity wasn’t sought out — the schism just happened to cut straight through this part of Europe. Even today’s dominant Islam was once just a simple way to pay lower Ottoman taxes. Ethnic identity and independence have always been important to Albanians. Religious identity, one could argue, has not.

So what does all of that mean?

In short, it means Albania is one weird place to be an ambassador of the Vatican.

I may have first known Albania through Harry Potter, but once I was on the ground, my experience was a bit more Princess Diaries. Another favorite of my tween years, this Meg Cabot book turned Anne Hathaway movie follows Mia Thermopolis, an ordinary American teenager made suddenly extraordinary by the discovery that she is heir to the throne of a little-known European state.

From shuttling around Tirana in a towncar decked with Vatican flags to nodding along to speeches in Albanian before realizing there were translation headphones hanging from my seat, I spent the week feeling very much like the awkward teenager stuck in a crash course in princessdom. I even had my own equivalent of a debut state dinner. At a gallery opening and cocktail reception at Hoxha’s abandoned villa, I rubbed elbows with the prime minister, studied the Quran with a diplomat from Pakistan and greeted the French ambassador enthusiastically en français . . . before learning that, actually, this was the ambassador from Germany. Flitting in and out of the nunciature all week with a friendly nod to the gate guard, I felt I’d earned admission to a rarefied world I had little business being in.

Anyone involved in Albanian diplomacy right now should be at the top of their game, but the pressure is especially high for a nuncio, whose role is not just diplomatic but religious.

That wasn’t because I couldn’t see myself being a diplomat. Archbishop Brown believes more Notre Dame alumni should go into diplomacy, and he suggested I take the Foreign Service exam. He also told me not to tell my boss he said that, but I’m mentioning it anyway to prove my point: I could totally envision a life like Brown’s. My discomfort among the diplomats wasn’t impostor syndrome. It was the simple knowledge that the political stakes in Albania at the moment are remarkably high.

Four years into the accession talks, it is still unclear whether Albania will become a member of the EU. Many member nations favor Albania’s membership, but pivotal exceptions, like Germany, remain. Opponents fear Albania will bring instability to an already faltering EU. Supporters say that, without Union admission, a weak and isolated Albania could fall prey to the influence of nearby Russia or even the threat of homegrown jihad. Things may not be rosy in the Eurozone at the moment, but most Albanians see membership as preferable to their current circumstance. Even the charismatic young mayor of Tirana calls himself “the mayor of Plan B” — the city people move to when their first choice, leaving the country, doesn’t work out.

Albania is actively presenting its best face to the world, and its diplomatic corps is a crucial part of that effort. And the Holy See sending a suave ambassador from the United States? It certainly doesn’t hurt.

Despite his lack of formal training, Archbishop Brown is every bit the diplomat. He looks the part, keeping fit through a passionate running habit and favoring Notre Dame’s Main Building-chic style of Roman collar and suit coat. Thanks to two and a half decades living abroad, he plays well with others, too, counting emissaries like departing EU ambassador Romana Vlahutin among his circle of local friends. He’s fluent in two languages and passable in a handful of others, including Albanian, which he’s slowly learning through three private lessons a week.

Anyone involved in Albanian diplomacy right now should be at the top of their game, but the pressure is especially high for a nuncio, whose role is not just diplomatic but religious. The harmony between Albania’s Muslim majority and its Catholic and Orthodox minorities is the nation’s major selling point, but if that harmony collapses, more than just EU membership is at stake. Albania sits along several intercontinental migration routes. Social or political instability could make it a fertile new battleground for Muslim-Christian or Muslim-Muslim conflicts already simmering in the Middle East and North Africa. The country doesn’t want to see that happen. Neither does the Vatican.

Typical ambassadors are the voice of their home countries in the countries where they are stationed, and Brown plays that role — “nuncio” is derived from nuntius, the Latin word for “messenger.” But, when the country you represent is an ecclesiastical city-state, the role also means you speak for the Catholic Church.

Brown doesn’t lead Albania’s 300,000 Catholics, he’s quick to point out. That’s the job of Tiranë-Durrës archbishop George Frendo. Brown’s duties are more organizational, helping identify potential bishops and welcoming diplomatic visitors. But, as a representative of the Church, he — like Frendo — often appears at official functions as the delegate and local figurehead of his faith. And that visibility is crucial.

On my first day in Albania, I attended a multinational conference devoted to Albania’s interreligious harmony. Brown, Frendo, the Orthodox archbishop Anastasios, the Muslim community chair Skender Brucaj and the Bektashi leader Baba Mondi were all on hand, signing a resolution committing to religious dialogue and posing for a photo.

The group convened again the next night at the gallery opening, with Prime Minister Edi Rama presenting tokens of appreciation to each. Rama echoed something that came up repeatedly in my conversations throughout the week: This diversity is Albania’s trademark and its gift to the world, he said. As long as our imams and bishops keep smiling together in friendly photo ops and our nuncio keeps blending in as a personable, productive member of the diplomatic corps, the rest of Europe should want to be just like us.

Let’s go back to that sunny Sunday on the coast.

The nuncio, driver Gjergj and I — and a few hundred other people — have come to the Cape of Rodon to celebrate the birthday of Skanderbeg, a national hero born nearby 613 years ago. Skanderbeg was Catholic, so today’s festivities will be, too. Archbishop Brown concelebrates Mass in carefully practiced Albanian, and then the party begins — folk dancing, music, merchandise booths. I chat with two teenagers eager to practice their English and watch as a nun reclines on the edge of a bunker for a quick phone call. Beyond the clifftop where we’ve gathered, bright blue waves crash onto a beach that looks like it hasn’t seen sunbathers in 100 years.

Archbishop Brown says he wants to stay in Albania until he retires, and it’s not hard to see why. It has wild mountains and pristine white sands, and, with bunkers and murals and dead-end dirt roads, it will always keep him alert. But there’s more to it than that.

On his first night in Tirana, Brown took to the terrace of his new residence to look out at the city. A few meters away across a courtyard, he saw a woman hanging up laundry on a nearby roof. She wore white robes with a distinctive blue stripe around the border — the habit of the Missionaries of Charity. The priest and the sister exchanged looks of surprised recognition and a wave.

It turns out that the Albanian outpost of the Missionaries — the order Mother Teresa herself began — is located directly behind the nunciature. Brown celebrates Mass there every other week.

“I want to believe that Mother Teresa had some role in my assignment to Albania,” he told me one day after Mass at the convent. Brown did regular work with the Missionaries during his time in Rome, and he got to know their now-canonized founder in the final years of her life. “I have the greatest respect and love for her and for the religious community that she founded. In many places of the world, when things go really, totally wrong, when things are very, very difficult, the Missionaries of Charity are still present. They don’t leave.”

As long as Pope Francis will let him stay, Charlie Brown doesn’t intend to leave either. There is work to be done. Albania’s Catholics are recovering from deep, recent wounds, yet Brown treasures how they interact so freely and lovingly with their brothers and sisters who practice Orthodoxy or Islam.

“The whole thing has been a great joy for me,” he says. “A great joy.

“I basically left America in 1991, and that’s what, 27 years? I’m used to living as an expatriate in that sense,” he explains. “For me, though, it’s a good image of the Christian, because we have no lasting city.” Not Dublin, not Tirana, not South Bend.

We are pilgrims, Brown says — and a cliff on the edge of the Adriatic is as good a place as any to spend a few years of the journey.

Sarah Cahalan is an associate editor of this magazine.