The warning crackle of an antiquated sound system broke into my lesson, followed by the school secretary’s urgent voice, “Teachers, check your voice mail immediately.” Phyllis liked to be in charge, and she repeated the message once more to show that she was. All of us teachers, even Mrs. Lawrence, a confident, professional 30-year veteran, were caught off-guard and fumbled our way through this first lockdown drill of the year. We had briefly discussed these drills during our summer meetings, but the talks had dissipated among such concerns as curriculum, dress code, student discipline and parental involvement.

Heidi Wallace was the newest faculty member at our small parochial school, hired right before the first day of school. She taught science classes in the room across the hall from me and hadn’t been privy to our summer discussions about a more thorough “red protocol” lockdown plan. While other teachers and I haphazardly yanked cords on window blinds, shuffled children to corners of classrooms, and grabbed for cell phones and classroom keys to lock doors, Heidi didn’t even realize that there is no voice mail system in our school. As she groped around her desk and leather bag for her cell phone to check her personal voice mail, Alice, one of her seventh-graders, let her in on the not-so-secret secret. “Teachers check your voice mail” is the cue to begin the most serious protocol of our crisis management plan, red protocol, the plan devised to protect all of us should an armed intruder enter our school.

Parents often comment on the comfortable, community feel that envelops their children when they’re under our watch. Although my colleagues and I are caring, dedicated teachers, the peaceful aura isn’t due solely to our presence. The physical environment contributes. Did the architects of the 1940s know about the psychology of color? All of the classroom walls and halls are made of concrete block faced with a calming cream and green marbleized swirl pattern, Marblock. I feel a calm when I enter the building each morning. In every classroom, a limestone pedestal juts out from the Marblock. Mary, the Blessed Virgin and patroness of our school, serenely stands upon that pedestal, ever at the ready to intercede and guide in times of distress. The Catholic faith teaches that we can rely on her intercession. Mary was a daughter, wife and the mother of a uniquely difficult child. Who better to help me as a daughter, wife, mother and teacher?

After that disastrous, unannounced drill, our principal organized the planning of a new, more efficient strategy. Everyone attended a meeting, from Mrs. Warner of the Lilliputian tables, chairs and tykes in the Pre-K; to Mrs. Shirley, who tends the snot-nosed, curiosity-infused intermediate graders; up through me, eighth-grade teacher of the child-minded, nearly adult-bodied. We met, discussed and prognosticated. A lunchroom worker emerged from behind the steam tables to detail every corner and crevice of the cafeteria; others described the access to the roof and the locations of possible safe havens among the closets, storage rooms and mechanical spaces of the building. The principal presented a video entitled RUN. HIDE. FIGHT., which realistically dramatized disturbing possible scenarios.

We concurred that we must have another drill, but this time only after practicing with our students:

and yes, we must have regular drills forthcoming;

and yes, we must make sure all students know the “voice mail signal”;

and yes, they must know to act immediately upon hearing it;

and yes, we must address with our students the real possibility that an armed intruder could calmly and coolly enter our miniscule, close-knit, century-old parochial school, intending to kill.

My eighth-grade students, during this year of the red protocol prep, were never as interested in practicing alliteration or analyzing a plot or comparing and contrasting characters as they were in identifying every possible red protocol scenario. They had long lists of “what if” questions asked with increasing detail and intricate twists of anticipated circumstances. Bradd, gruff, sturdy and bed-headed, asked, “Mrs. Therber, what if me an’ Jonny are taking the recycling out to the dumpster when the guy breaks into the building, an’ we hear shots, should we come in an’ tackle ’im or run to the church office and call 911?” — in their minds, it’s always “a guy,” images of Sandy Hook and the ensuing media recaps of Columbine and other grisly scenes sketch their mental visions.

One of two dark-headed, dark-eyed Theresas in the eighth grade, who prefers to be called Lopez to keep her identity separate from the other Theresa, asks, “Why couldn’t we just climb that ladder in the janitor’s closet and hide on the roof? He’d never know we’re there. Then maybe we could throw rocks down at him or somethin’ if he came out the doors.”

I answered most of their questions and simultaneously tried to identify the line between true fear of the unthinkable and their attempts to outdo each other’s predictive abilities. We needed to think through the possibilities, but was Bradd nervously reacting to the yet unspoken possible consequences of a red protocol or was he smirking at his own ingenuity? We had covered everything within reason. It was time to move on to more academic pursuits, and I warned that I was about to take the last question.

Maggie, waving her arm in the air, sliding first off one side and then off the other side of her chair, eyeball-implored me until I called on her. “Mrs. Therber, what if you lock us in while you check the restrooms, and we’re in the back corner with the lights out where we’re supposed to be, and you don’t have your key to get back in? Should one of us come and open the door to let you in?”

“Mag,” I said, “I will always have my key. It’s part of my routine. I’ve practiced. I’ve got a system. I’ll grab my key and phone, close the door, check the restrooms, let myself back in and we’ll wait for the all-clear, or do whatever our common sense tells us we need to do in the meantime.”

Maggie couldn’t stop. “But what if the guy has you in the hall, and he has a big gun, and he makes you say that we should let you in even though you do have your key, so we think you need in, and we want you to be safe, so we let you in, but he comes in with the gun?”

Would I RUN? HIDE? Before I had fully asked myself that question, the answer muscled its way into my mind and right out of my mouth with a clear conviction of force that I somehow knew would take over if necessary.

“I will not, no matter what, under any circumstances, ask you to open the door.” The next few seconds bore no smirks, no sound, no movement but wide eyes, and I felt mine filling with burning moisture quickly evaporated by a fierce, primordial urge — FIGHT! In that moment, we all, students and teacher, had moved from the imagined to the stark reality of what could be, unimaginable as it has always seemed.

I have wondered, could I ever really stab someone, shoot someone, or hit an attacker with a blunt object? Self-defense specialists show us the best way to kick an attacker in the groin, advise us to get a small handgun for the purse and learn how to use it, to carry pepper spray when out walking for exercise, to walk erectly, confidently, looking strangers in the eyes so as to not appear as a potential victim. What if I were being raped? Threatened with a knife? Could I actually damage another human being? If the situation ever arose, would something within me take over that would allow me to do whatever would be needed for my own protection? I’ve never felt confident in those imagined confrontations, confident that I could hurt someone badly enough to save myself.

When I was 10, a beastly fight dwelled in me. My little brother Jimmy was 3. He was scrawny, curly-haired, annoying and so afraid of bigger kids that he wouldn’t go with Chris, our 8-year-old brother, and me to the playground just down the block. We had finally convinced him to come with us by promising to push him on the swings. Only a few minutes into the foray, a kid my age named Ricky showed up and started in on Jimmy.

“What’s wong Jimmy-Wimmy, can’t say my name? I’m Ricky, not Wicky. When you gonna wearn your Rs and Ls, Jimmy-Wimmy? Go ahead and cwy wike a baby.”

Jimmy was crying and running home, but Ricky was relentless, chasing him. I chased Ricky, and that was when the fight came.

“Stop it, Ricky,” I commanded, as Chris watched from behind me, and Jimmy from behind Ricky.

“Make me.”

So I did. I pulled back my closed fist and propelled it into Ricky’s snot-encrusted nose. Blood spurted and he ran home. I ran home, too, dragging Jimmy — who eventually became a 6-foot-2, 220-pound Division I football player — by the arm. Chris told on me, and my mother wasn’t happy, but she wasn’t angry. Dad congratulated me.

I’ve never felt the fight come to life for myself. My dad once got upset with me when I was a teenager for “taking too much shit from people,” as he said, but that fight within me only awakens to protect others. No fight roils more suddenly, more fervently to the surface of a tranquil spirit than when the primordial protective instinct is triggered. It seems to do so independently and without need of my command.

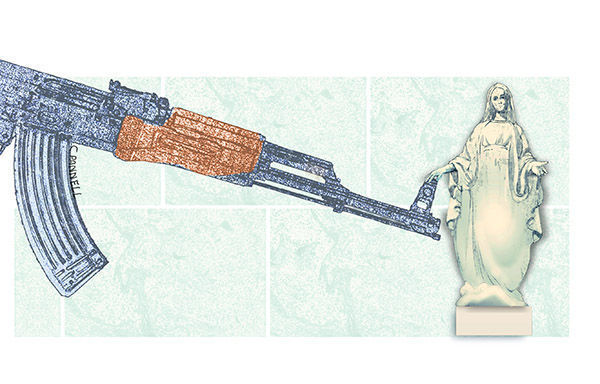

Standing in front of those hormonally charged innocents, among them Caleb, 6-foot-2 yet still afraid to read in front of the class, and Felicia, curvy, hippy and still into Hello Kitty, I discovered that I could definitely hurt someone. The possible evil became a vividly real image when projected through those kids’ eyes. The image produced tears, then the fight in me stirred and writhed out of that stark image. I would not open that door to reveal children huddled in a corner, peering out from around the bookshelves filled with Gary Paulsen and Suzanne Collins. I would not open that door to reveal children peeping out from under school desks stuffed with crumpled loose-leaf paper and zippered pencil bags. I would kill the guy — or die trying. I would grab for the most damaging weapon within reach, the statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary, fair-skinned, blue-sashed, hands clasped in prayer, eyes turned toward God, flowers at her feet, and 24 inches of heavy, club-shaped plaster. I would beat his brains out with a statue of the Mother of God.

We finally wrapped up our “what ifs” and returned to our regularly scheduled school day. Later, with my class gone to PE and the room quiet, I look at Mary so serenely poised there on her limestone pedestal. I imagine that Mary could have had that fighting thing within her. Having raised a son into adulthood, watching him help the poor, the diseased and the desperate, and preaching peace, only to be beaten, humiliated and tortured to death for his goodness: How could a mother not allow that protective beast within to act? Maybe agreeing to God’s plan from the beginning gave her control over the beast. Or maybe she did try to fight, and the scribes didn’t write it down for us to read these thousands of years since. Mary has been a spiritual help to me throughout my life. Now, I am forced to create a workable plan to thwart unimaginably evil acts. If run and hide won’t work, she will give me more strength in the fight.

Angie Therber teaches in a parochial school in Indiana and is working on a master’s degree in English. She and her husband, Joe Therber ’84, ’98MSA, are the parents of five children, all navigating various stages of education and life. The names of the people in this essay have been changed.