A few decades ago in Austin, I somehow found the guts to gather my meager savings and roll the dice to see if I could survive in New York City. I ended up in a furnished, basement-level room in Brooklyn lit by a circular fluorescent lightbulb that buzzed. It had a shared bathroom and a ceiling so low I could put my hand flat to it. From my only window, I watched people from the ankles down passing by on the sidewalk above me, and for a short period I became somewhat current regarding footwear.

The job I found to sustain my new life was at Astor Wines & Spirits in Union Square. I’d been the beer and wine manager at Whole Foods in Austin, so this seemed, for someone not reading the tea leaves, a logical position. But the pay was lousy and the work physically grueling. Even so, I planned for this job to carry me until I could find my way into the theater scene. I’d discovered playwriting in Texas, and I probably wouldn’t have lasted three months in New York except that a play I wrote had won a contest and was to receive a small production.

This would’ve been in the mid-1980s. Truthfully, my play looked good on paper but didn’t work onstage — it had already failed in Texas, but I was blaming other factors until this production, a short and ill-conceived showcase in a tiny, dank theater in the vicinity of Times Square, drove the point home. The experience was humiliating and beat me up, as did the job and the city itself. After nine months in New York my health was shot and my bank account empty, so I had to bail for home.

But one evening before I left I was stacking cases of wine in Astor Wines’ basement when a news report came over a transistor radio announcing that the first woman in something like 40 years was about to be executed in North Carolina. The kicker was what she picked as her last meal — Cheez Doodles and Coca-Cola. Her choice barnacled to my mind, not so much because it was a “great idea for a play!” but because it was something I didn’t understand and I had to find a way to understand it.

We keep at it because we love it, but time does pass, and after decades of heart, blood and bone put into these small successes, it’s easy, especially on bad days, to wonder what the point of it all was. What did one tiny show or story matter?

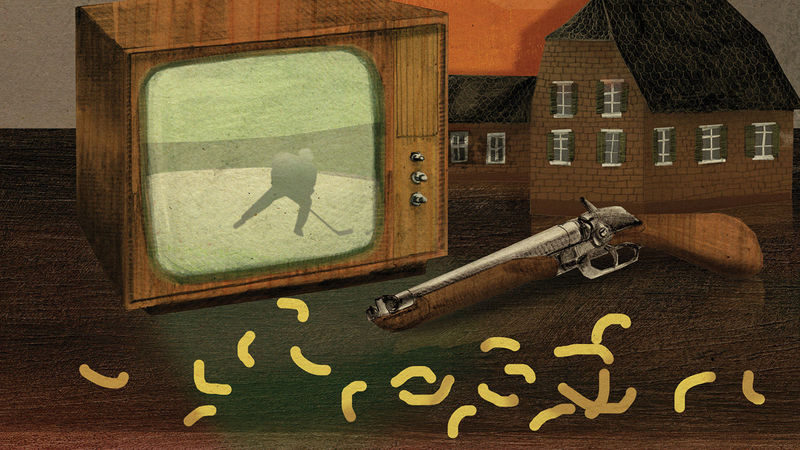

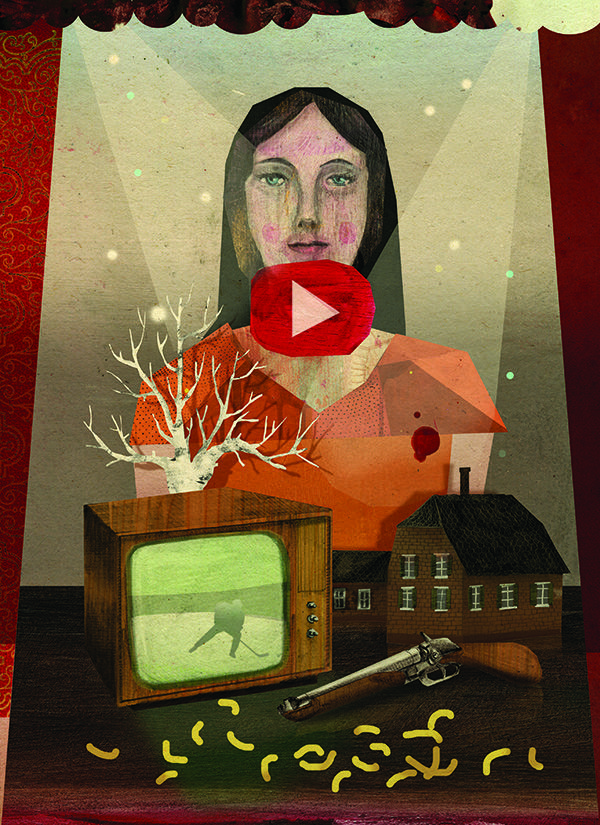

RECOVERING BACK IN AUSTIN, I found myself haunted by New York. I’d be sitting in a café and writing, only to look out the window and flash back to images from the city, most involving snow falling or the subways or the old buildings. As I couldn’t shake the story I’d heard in Astor Wines’ basement, I began work on a new play I called Cheez Doodles. In it a middle-aged woman named Cindy Jo sits on a stool happily munching from a big bag of Cheez Doodles and sipping on her Coca-Cola as she leads us down the trail of her frustrated life with her pig of a husband, Wayne, to the point where one day she walks over, picks up Wayne’s Browning 12-gauge shotgun, and before she knows it she’s “blowed his head all over the hockey game on TV.” Wayne’s sports addiction was one particular sore point of their marriage.

This little play would receive six separate small productions — more than any other play I wrote — mostly in Texas, but also in New York and Los Angeles. You can see why. It’s a one-woman show, it’s comical (for the most part), staging is minimal and the damn thing always worked, no matter the actress or her age. Every few years it’d pop up; someone would want to do it. I don’t know if I ever made a penny off of it, but, truthfully, I made very little money off any of my plays.

I eventually shifted from playwriting to prose. I moved back to New York, where I got an MFA in fiction, wrote some short stories, spent an enormously long time learning how to write novels and then started working with nonfiction. Life happened, of course, and years went by, as they do. I had fond memories of Cheez Doodles. It was my most produced play. Still, I doubt we ever got a hundred people into the theater to watch it on any given night.

From my perspective, Cheez Doodles was like a painting everyone liked that an artist was able to place in a number of small shows. I’d made some people laugh, maybe even startled them for a moment. But who knew if anyone besides me, a few friends or the actresses who performed it even remembered it. And that’s art, right? You try your best to nurture this thing that’s come from your hands to viability. That’s all you can do. And then you move on.

IT’S HARD TO IMAGINE the sheer quantity of live performances each year in little theaters across the country. Add to that all the paintings hung on tiny gallery walls, the poems that found their way into small lit journals, the recordings of midlevel bands. We keep at it because we love it, but time does pass, and after decades of heart, blood and bone put into these small successes, it’s easy, especially on bad days, to wonder what the point of it all was. What did one tiny show or story matter? How delusional have you been? You know being delusional to some degree is part and parcel for any artist, good or bad. It’s a necessary card in the deck you’ve been playing, but that’s hardly a comforting thought during a reality check.

In 2012 Cheez Doodles popped up its head again. A friend and collaborator had written a play he was getting produced in a small theater somewhere in Kentucky. It was not quite full length, and he needed another 20 minutes to fill out the evening. “Sure,” I said.

He was going to go, of course, and I think he believed I should go, too. But I’d already seen a half-dozen productions of my play, one in New York. Cheez Doodles’ life was its own now, and its most active days were behind it. Also, and this was no small factor, I was flat broke. There was no way I could fund the trip myself. So I wished my friend the best.

When he returned, he told me a young woman around 20 years old named Lindsey had played the part of Cindy Jo and had done a terrific job, had really brought some spunk to it. Which was great to hear. Twenty is on the young side for the part, but I’d seen it work with women in their mid-20s, so why not? He had recorded both shows with his iPhone from his table for archival purposes, and with a warning that the quality of the recording was low, he sent me a link to where he’d stored them. I opened up the first file to watch Lindsey step to the stage. She had dark hair and big eyes and wore an orange jumpsuit. Yes, she was young, but she had a real grip on the part (I suspected she was tapping into a relationship with an ex-boyfriend). Still, I found the quality of the video annoying, and, after all, how many times did I need to see this play in one life? So I closed the file without downloading.

A month later my friend sent an email to tell me Lindsey had died in a freak accident. It was a strange, unsettling moment. I mean, what do you say? And to whom? So I went on. I had prose projects I was trying to finish and was struggling to scratch up money for rent.

Two years later, an online acquaintance mentioned she’d discovered her “Other” folder on Facebook, an equivalent of a spam folder, and found some messages that had landed there by mistake.

I didn’t even know I had an “Other” folder. I followed her directions to it. Yep, there were messages inside, none written later than 2012. Most looked spammy but the most recent was from a woman whose name I didn’t recognize. When I opened it, I saw it was from Lindsey’s mother. The mother of my actress.

Her message was perhaps the most generous response to my work I’d ever received. Among other comments, she said that at her daughter’s funeral one of Lindsey’s friends came up to her and told her he wasn’t sad because he was thinking about how funny and great Lindsey had been in Cheez Doodles.

She said that moment provided her one of the very few smiles she managed that day. I didn’t know the circumstances, but it was obvious Lindsey’s performance that weekend had been a significant occasion for her family. Maybe it was the strongest performance of her life, or her only adult role, or the first time she stepped onto the stage as a professional, which changes everything for a young actor, no matter the size of the role or its venue. But clearly she had a definitive moment onstage as a young actress, and only because once upon a time, many years ago, I heard a random newscast in the basement of a liquor store and got it into my head to write another play.

But I was horrified — this message had sat in my “Other” file for two whole years. I immediately responded to Lindsey’s mother, apologizing for missing her note.

The next day she responded, thanking me for writing her, and she told me again how much the play had meant to her family. She even told me that on special occasions she took the script to her daughter’s graveside. She sent two headshots of Lindsey in heavy makeup, probably from high school theater productions. Lindsey had a thin face and dark, determined eyes, and looked very familiar, like those girls I used to see in New York, spirited, fearless, decisive girls from dull suburbs and small towns who’d worked and scrimped and saved and gambled it all for a plane or bus ticket, and now, by God, they were here and they were going to do it! Not unlike me, I realized, though these girls tended to be tougher than me.

Her mother also sent an eight-second video of Lindsey in her home, about to run lines for Cheez Doodles, where she first bursts into sharp laughter, then tells her mom to stop filming. I played the video multiple times to take in that staccato laugh. It was forceful and clear, what you’d expect from a young actress with purpose. But it was over so quickly. Her mother wrote that this was the only video she’d made during this production. She wanted to know if we’d taped any of the rehearsals.

I sat back in my chair. I hadn’t downloaded the performances when I had the chance. Two full years had gone by. Thankfully, when I contacted my collaborator, he was able to send me the link to his recordings. So with a cautiously crafted email (after all, the subject of death is prevalent in my play), I sent Lindsey’s mother the link. I didn’t hear anything the first day. I tried not to worry.

The second day she sent me a long email telling me it had taken her husband five full hours to figure out how to download and transfer the recording to a DVD, but he’d finally succeeded. And she’d watched it — two performances of her daughter at 15 minutes each — five times already. She said she would be forever in my debt.

It was so much. Too much for what I did, for what I do. We write these stories and dance these dances and speak these lines and sing these songs because we can’t imagine not doing this. But we doubt ourselves, never knowing if we ever really reached anyone, if all this was for nothing.

At least I have. And only because of a tragedy, and a letter from a mother buried in a spam folder, and a random comment on Facebook that guided me to that letter, did I find that perhaps the smallest, least production of a play I’d written so many years ago, one I’d entirely let go of, may have had the most significant impact of anything I’ve done.

We may never know what spunky girl in Kentucky got her last, best chance to show her community she was a born actor because we wrote a short play, or what middle-aged man seeing our sculpture in some small town suddenly decided to take up pottery, or what couple fell in love while we sang in a dim, clattery bar.

But what we can know is that we don’t have to see the results to understand these things happen. And that what we do matters.

Steve Adams lives in Texas, where he is a writing coach (steveadamswriting.com). His memoir, “Touch,” appeared in The Pushcart Prize XXXVIII. He has been published in this magazine as well as in Glimmer Train, The Missouri Review, The Pinch and elsewhere. His plays and musicals have been produced in New York City.