The Haitian doctors’ strike ended last week and it is unclear if there are any winners. The conditions in which the striking doctors — medical residents in Haiti’s public hospitals, to be precise — work are appalling and the low pay was galling, but without the doctors, hospitals shut their doors and the poor were left to take care of their own illnesses and injuries for nearly five months.

At issue were three problems plaguing these public hospitals: poor resources, inadequate oversight of the residents by their supervising physicians, and low salaries. Prior to the strike, resident physicians earned about $125 a month while working long hours. That’s maybe a quarter of what a nurse makes and is roughly equivalent to the earnings of the housekeeping staff. The theory in medicine — in Haiti as in many other countries — is that residents are learning and are therefore receiving benefits beyond their pay in the form of education. The strike raised their monthly earnings to about $400 — still embarrassingly low.

In the United Kingdom and the United States, efforts to organize doctors and address grievances have so far remained quieter, while raising the same serious ethical questions about doctors’ conflicting responsibilities to their patients and to themselves, about where the line between altruism and egoism is crossed.

In the U.K., doctors-in-training have been fighting increases in work hours, a contraction of pay, and patients’ benefit cuts within the National Health Service. At first, organizers limited their tactics to hospital staffing reductions they believed would help them gain the upper hand and force an improved negotiating position. Then, this past April, they implemented a two-day complete strike. An estimated 80 percent of junior doctors participated, despite questions about what would patients do. Now, with the junior doctors’ grievances still unresolved, the British Medical Association planned to strike for five consecutive days, possibly canceling tens of thousands of surgeries and an estimated one million office visits. Leading media outlets have characterized the row as a proxy war between the British government and the medical establishment over continued cuts to the NHS. Both sides are digging in.

One can argue that short-term suffering is worth the long-term gains in workplace safety and satisfaction, both for doctors and the public. But at what point do the benefits of a strike outweigh the problems?

Meanwhile, in the United States, internal medicine physicians are locked in a protracted battle with the American Board of Internal Medicine, the private and self-appointed body that until recently held a monopoly over board certifications. Thousands of doctors, including myself, have refused to pay the $200 annual professional fee or to enroll in the board-required continuing medical education classes that show no evidence of benefit for us doctors or our patients. Many of us openly believe the board is guilty of fraud and profiteering. We have decided to not participate in the program at all. But that admittedly leaves patients, hospitals and insurance companies with the burden of deciding who among us meets quality standards.

While different in their particulars, the situation in each country raises questions about doctors’ responsibilities to their patients and the public. Doctors often fight for patients’ rights through administrative and legal channels — by lobbying hospital administrators, insurance company bureaucrats or government officials — and the public generally supports the fight. When discussing our own rights, however, we enter a murky area: Is what is good for doctors always good for patients and public health?

I have always believed in the power of unions to achieve goals that individual workers can’t reach on their own. Weekends, paid vacations, employer-sponsored health insurance and maternity leave are all examples of basic workers’ rights gleaned in the U.S. through organized labor. I also support my fellow physicians’ right to earn a living wage commensurate with their education and training.

Globally, members of my profession, including those still in training, are well-educated and stand among the top half of earners. Sympathy for our salary or benefit fights is not always widespread, least of all when work stoppages have an immediate impact on patient care. Certainly, one can argue that short-term suffering is worth the long-term gains in workplace safety and satisfaction, both for doctors and the public. But at what point do the benefits of a strike outweigh the problems?

In the U.K., senior doctors should be able to cover medical needs during a short-term strike. The outcome will be limited in most cases to delays in patient care. In Haiti, however, the strike caused deaths as the poor had no place to seek medical care for several months.

The stakes in this Caribbean nation are arguably higher, too. Government here accounts for only a reported 20.6 percent of total health spending — fourth from the bottom of the World Bank’s 2014 data and far lower than either the U.S. (48.3 percent) or the U.K. (83.1 percent). Woefully underfunded, public hospitals often lack essential supplies such as gloves, gauze and intravenous fluids. Family members purchase supplies and medications for their loved one’s care at private pharmacies. Patients are often sent to private labs to obtain services as basic as chest x-rays. Hospital staff generally do all they can for their patients in these circumstances, but the odds for optimal outcomes are always against them. It is no wonder that morale among healthcare professionals in Haiti is so low, while burnout and turnover are quite high. As in the U.S., the poor suffer the most as a result of a broken healthcare system.

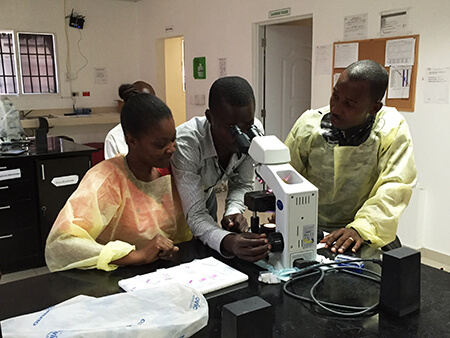

I saw this up close after my nonprofit organization, Innovating Health International, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, opened Haiti’s first publicly available pathology lab outside of the capital, Port-au-Prince, in May. Our timing was unfortunate. The strike meant our laboratory technicians had very few tissue samples to test, setting them behind in terms of training and practical experience. Our program to train doctors and nurses at Haiti’s nine largest public hospitals in cervical cancer screening has suffered a similar setback. With no one to train, our equipment has sat idle in a Port-au-Prince warehouse.

Similarly, the young doctors in these state-run hospitals have missed five months of their medical residencies — over 10 percent of their professional training time. Nobody knows now whether they’ll be required to make it up. The result will be either undertrained doctors or delayed emergence into the profession. Neither option is attractive.

Still, the Haitian residents received their badly needed pay raise. The government committed an additional $12.5 million to the health budget, roughly a 6 percent increase. While this could be seen as a victory for both the doctors and patients, the human cost of the last five months cannot be forgotten.

Vincent DeGennaro is an internal medicine doctor and global public health specialist in the University of Florida’s Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Medicine. He works mostly in Haiti with the nonprofit Innovating Health International. See his An American Doctor in Haiti blog.