I play the piano, not well. When, early on in my musical training, I attempted to play a standard beginner minuet for my mother, she said I sucked. I’m quoting. Later, dying of cancer and high on morphine, my mother swore that I’d been right when, in the fourth grade, I’d convinced her to let me quit taking the piano lessons that she’d insisted on. “You have no talent,” she said. “You take after your father.”

Despite my mother’s assessment of my abilities, I didn’t quit as I had in fourth grade but kept at it, slowly improving, until — right around the time that my eldest son, a soldier in the Israeli Defense Forces, called to say he probably wouldn’t be in touch any time soon because his unit was going into Gaza — I was advanced enough to embark on Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” Completed while the composer lived in Leipzig in 1723, it was transcribed for the piano in 1926 and has since become one of Bach’s most enduringly beloved works.

I have a great recording of it by the pianist Leon Fleisher and had wanted to play it for a long time when my piano teacher, Tom Parente, said I “had the chops for it.” My mother, by then, had been dead for a decade, and my son — a chayal boded or “lone soldier” — was just a few months shy of completing his military service and was engaged to be married.

I didn’t begin playing the piano in earnest until my mid-40s, when I was sufficiently recovered from my own bout with cancer to start thinking about what I was going to do with the rest of my life now that it turned out that I’d have one, and my mother, less fortunate, had less than five months left. So my learning curve was steep, and not just about matters of the heart, of grief, of anger, of the moods and measures of the absolute absence, the utter lack, that is death. I was already a decade older than Mozart was when he wrote The Magic Flute (and subsequently died), and a complete neophyte. Just about everything I now know about music I learned either from Tom, my teacher, or from listening to Professor Robert Greenberg’s lectures on CD, which I order from The Great Courses catalogue.

I didn’t know anything about Leon Fleisher until I stumbled on his album Two Hands and learned that Fleisher is not only one of the greatest pianists the world has ever produced but one of its greatest mensches as well — a consummate artist who, at 36 and at the peak of his career, lost the use of his right hand to something called focal dystonia but continued playing the piano with his left hand, teaching, conducting and inspiring God knows how many young musicians (and then recovering the use of his right hand by the grace of modern medicine).

In any event, I was no Fleisher. More to the point, no matter how often I practiced, or with what amount of intentionality, concentration and devotion — feeling states that could be fleeting for me during normal times — now that my son was being sent into Gaza with his unit of the Israeli military forces, everything that had once been solid and good for me fled from my grasp like the tail end of a dream. Words themselves became insubstantial, and musical notes — the most abstract of languages — were black squiggles on a white page.

But I loved “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” so much that, at times, I actually obeyed Tom’s pedagogic direction and approached it slowly, measure by measure, feeling it through my fingertips, feeling the weight of the keys under my finger-pads, trying to listen to the beauty of the music rather than either my worst fears or my lifelong need to get “it” right, no matter what “it” was, an emotional strategy that also goes by the name “perfectionism.” As my natural inclination is to force myself to finish — and thereby conquer — any given piece of music as quickly as I can, and to hell with what it actually sounds like, Tom’s approach to teaching constituted the unlearning of everything I’d been taught from the cradle about how to do anything at all. So it was sort of on-again, off-again with me and Bach. Which drove me insane, as I so desperately wanted to play the piece the way it was meant to be played.

“Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” the English name for the 10th part of the cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben, expresses, in music, my own longing to give my heart to God: to somehow be a part of divine will; to take dictation from someone or something other than my own nagging and petty inner yap-yap dog. Bach mainly wrote music for the Church; that’s how he made a living. It was the olden days in Europe, specifically the Baroque period, and if you wanted to make a living as a musician, well, it was either working for some rich prince or for the Church. If neither was an option, it was fun in the Westphalian welfare line. Bach wrote hundreds of cantatas, choral music that was sung, usually in praise of Jesus. How he did this is an utter mystery, as was how he came upon counterpoint, as was nearly everything else about Bach.

A translation of the first four lines from the original German score:

Well for me that I have Jesus,

O how strong I hold to him

that he might refresh my heart,

when sick and sad am I.

Sick and sad am I, and at home, the days and then the weeks passed quietly, with no word from our son. Every time the phone rang I could feel my blood pressure rise; each time I picked up the receiver, I prayed that I wouldn’t hear an official-sounding voice speaking English with a Hebrew accent — “Hello, geveret, I am being sorry that to telling you is about your son” — and I was still struggling with “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” My husband and I went on a strict news diet, but still the news trickled in: three Israeli soldiers killed in a tunnel blast; another by ambush; two more by sniper fire. Not to mention the dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of innocent Gazan civilians killed — but none of these people, nameless and faceless as far as U.S. news outlets were concerned, were my son.

Even so, I prayed for all of them: for the innocents on both sides of the border, for the soldiers, for Jews and Christians and Muslims — pretty much for everyone whose sole purpose in life, whose raison d’etre, didn’t include murder. But I prayed for my son and his pals the most. I knew it: God knew it. And if there’s one thing I know, it’s this: You can’t bullshit God. You may not believe in God. But you can’t bullshit Him. In this case, I didn’t even try.

An email from my sister-in-law, in Jerusalem, saying that she still hadn’t seen my son’s name in any of the news reports. This, she said, was good news. Another from my son’s fiancée, saying that it was another unit — and not the one my son was in — that was taking the brunt of the fighting. Another email, this time from Tel Aviv, with much the same information (“He’s not on the most recent casualty list”). And then nothing — no email, no phone calls, no text message saying that our son had broken his leg (my own go-to fantasy) and had to be hospitalized, and no news about de-escalation, either. Just more war, and my son somewhere in the middle of it.

His decision, more than three years earlier, to make Aliyah — literally to “go up” to Mount Zion but commonly understood to mean the act of moving to Israel and becoming an Israeli citizen — came out of his own conviction that being a synagogue-going, communal-centric, ethical American Jew wasn’t enough. He felt compelled to serve the Am, the people, and therefore, a month after he had completed college, off he went to a country that amounts to little more than a sliver of sand the size of New Jersey, with two suitcases, a few books and — though he had not been raised in anything like an Orthodox home — a set of phylacteries. My husband and I were proud of him but sad that he was so far away, and, once he became a soldier, occasionally worried. Even so, as the months and then the years went on with no injuries more serious than really bad blisters, we more-or-less relaxed, understanding that, first of all, our son was a grown man with the right to make his own decisions, and, second, that the path he had chosen was noble. Also, our son’s girlfriend (then fiancée) had also made Aliyah. This was good: our son had a partner; he wasn’t alone. And Israel was relatively calm. Until it wasn’t.

Music is famously a consolation for the bereaved, and just as famously an accompaniment for joy and celebration. But for me, learning to play the piano in midlife, it was about a whole nexus of things, including that I’d long regretted my fourth-grade decision to give up on the piano (when it got hard); my conviction that in order to be an educated person I needed to know not only how to play an instrument but something about music itself; the certainty that my own education was deeply lopsided and therefore deeply flawed and that I myself was deeply lopsided and therefore deeply flawed; and that the piano itself, with its elegant black-and-white keyboard and mathematically elegant simplicity, its resonance and range of expressiveness, somehow held out the possibility of redemption. If I could only master the basics — some (easy) Beethoven, some easy-enough Bach, some Mendelssohn, some Mozart, a sonatina there, a prelude here — then maybe I’d find peace, that my lifelong bout with depression and anxiety would abate, and in its absence, something better would flow in.

Before the war in Gaza, our son had told us all kinds of things about his experience in the military, including that, like all soldiers, he slept with his gun nearby, that he’d developed what is known as “shwarma skin” from crawling on his belly through the desert during training, and that his back hurt from carrying his unit’s machine gun, but all of these things were par for the course, unpleasant but hardly alarming. Now, we heard nothing. Although I tried to avoid anyone who might be inclined to pepper me with questions that I had no way of answering, I was both unable and unwilling to seal myself off completely. Mainly people were sympathetic, sensitive to my state of anxiety. But not always. On one occasion the grown daughter of a friend of mine insisted on telling me about the death, in the Gaza war, of a childhood playmate of hers.

At home, I sat in front of my piano, willing myself to play Bach the way, I was sure, that Bach wanted me to play him. But every time I got to the slow chordy-passage toward the end of the first section, I panicked. I also panicked at the next to the last bit, when Bach lets loose with the most beautiful, elegant and simple descending melody ever composed. I either froze, blanked out or played the wrong notes. And then I’d sit there and weep with frustration. Then someone would call and ask me if I’d seen the latest posting from the online version of The New York Times about Israeli soldiers being trapped in a tunnel in Jabalia, and I’d go back to murdering Bach and weeping.

It was in this state that I appeared on my usual day for my regular piano lesson, sat down at Tom’s beautiful black Steinway, and proceeded to make Bach sound like “Chopsticks.” My entire body tensed up. I was dripping with sweat. My heart pounded. Observing my discomfort and frustration, Tom got up, came over to where I was sitting at the piano and, lowering the lid over the keyboard, said “Let’s try something.”

To which I said: “Oh my God! No! No! Don’t make me do that thing again. I just can’t. I just can’t. I just can’t. I hate that thing. Please don’t make me.”

The thing I was objecting to is playing with the lid semi-lowered, so rather than relying on my eyes to find the correct notes, my fingers would have to do the walking. This is an exercise that Tom had given me before, with another piece — the “Adagio Cantabile” of Beethoven’s “Sonata Pathetique.” While it had, in fact, helped me immeasurably, I knew it wasn’t for me, not then, not with Bach, not with “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.”

Tom took a step back and said: “Jennifer, I can’t teach you unless you let me teach you. But time and time again, I want to show you a technique, but you’re so closed to it and so rigid that I don’t have anywhere to go.” And the thing is? I love my piano teacher. I love him, his wife, his two kids and his bratty little white yappy dog, Oliver. It was all I could do not to burst into tears of sheer humiliation and beg him for forgiveness. But Tom — who wasn’t in fact my stern, elderly father — just smiled and said: “Okay?”

“Okay,” I said.

So he showed me this thing where you lower the piano lid over the keys and pretend that you’re playing the piece, only, of course, you’re not: you’re fingering wood. But in your mind you get to sound like anyone you want — in my case, Leon Fleisher — and connect with the music, and the physical movements that produce the music, without pressure.

At home, I practiced the famous, gorgeous opening chord progression: G, C, G, B minor, sinking into the keys, trying to hear the angels but hearing instead my own fears. I’d bat them away, only to over- or under-pedal, or pedal at the wrong time, and then I’d rededicate myself to the gorgeous simple ascending melodies. There was no more news, and then the news that there had been another incident in a tunnel, another death of an Israeli soldier, only this time it was from our son’s team.

The second four lines, again from the German:

Jesus have I, who loves me

and gives to me his own,

ah, therefore I will not leave Jesus,

when I feel my heart is breaking.

And it wasn’t our son, but a friend of his this time — he was 18 — and they carried his exploded body out of the tunnel amidst chaos, and in early August, my husband woke me around 6 in the morning to say that he’d just gotten an email from our son’s fiancée in Jerusalem, saying that our son was on a bus, heading home, and a week later we ourselves were in Jerusalem, gathered among hundreds of others at the cemetery at Mount Herzl — the mountain of Remembrance — to say kaddish for our son’s friend as the young man’s parents, marking the end of shiva, dissolved in grief, and, truly, my heart was breaking — for all of them, for all of this — and then we were at our son’s wedding, and a week after that the war was over.

Bach wrote everything for the glory of God, secular as well as sacred music. But we Jews never developed a sacred synagogue music — at any rate, not a grand one, the likes of Bach’s cantatas or Handel’s oratorios, perhaps because during the flowering of the European musical tradition most Jews were being systematically impoverished and oppressed by anti-Semitic laws, hounded out of their homes and murdered. I rarely get the high from Jewish sacred music that I get from the greatest hits of the Church. This worries me a little, as does the fact that I love Gospel music in general, so much so that sometimes I’m compelled, as if by nature, to put on my favorite-ever recording, “Jesus Is My Rock” by the Rev. Gerald Thompson and the Arkansas Fellowship Mass Choir, and dance around the kitchen like a crazy person.

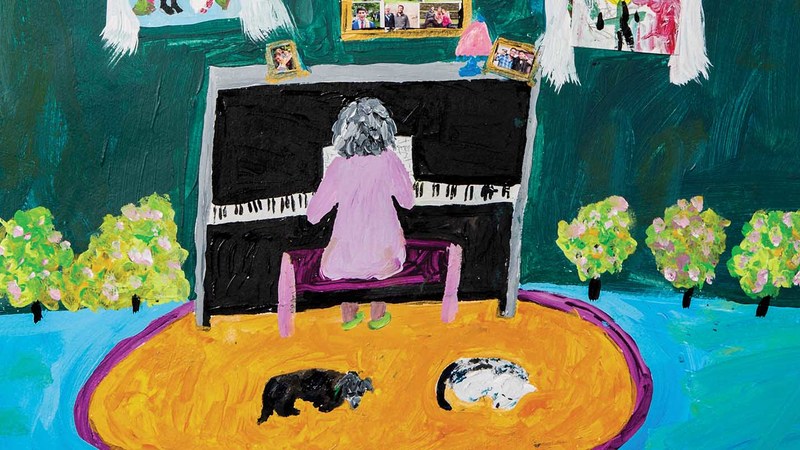

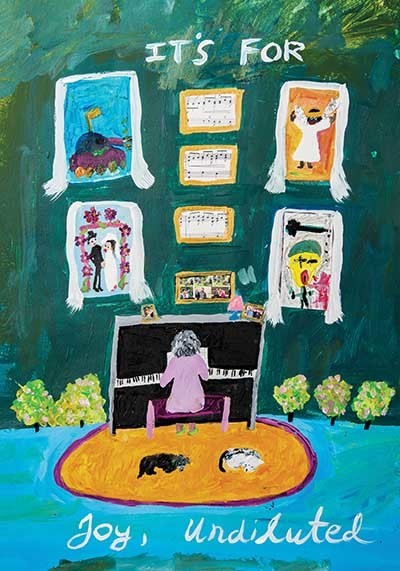

I still haven’t gotten over the first time I saw Alvin Ailey’s “Revelations.” It was 1975, I was in high school, and my mother took me to see the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater at the Kennedy Center. “You’ll just love this,” she assured me. Love it? Not exactly. The moment I heard the first chords of the first song, “Fix Me Jesus,” I knew something about myself that I’d never known before, and it was merely this: every particle of me yearned to be in communion with God — but not the ethics-giving God of my family’s synagogue, or the God who talks to people in the Genesis stories, or even the Divinity of Creation itself. It was something else, something more, something greater that I yearned for. It was joy, undiluted.

And that’s how I learned to play the piano.

Jennifer Anne Moses is the author of four books, including Visiting Hours, a novel in stories. Her essays, short stories, and opinion pieces have been widely published. See her website at jenniferannemosesarts.com.