On a peaceful Saturday morning in early September I sat in my backyard, savoring the scene before me: the grass and trees and black-eyed Susans, all feeling different now — as the sunlight and scents took on an autumn mood. It reminded me of a memorable essay from years back, and that got me to conjuring a list of all-time personal favorites published in the magazine over the years. I decided to share them with you, a new one each Saturday morning until the calendar reaches 2024. For the Spring 2016 issue, we asked some of our favorite writers to have fun with the concept of Fun. For Dave Devine ’94, “We are pirates,” appeared in his head and led him on a chase through the journeys and joys of parenthood for this endearing gem. —Kerry Temple ’74

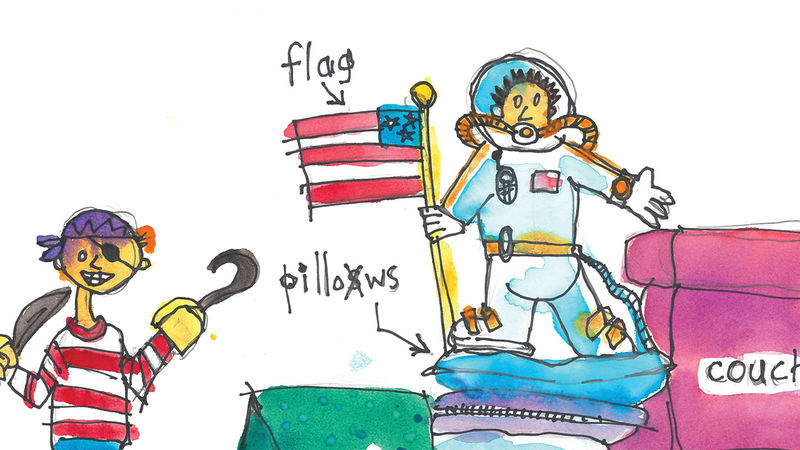

We are pirates. Nice ones, but still with the cutlasses and cannons.

Or we’re astronauts, hurtling through space, and the basement couch is a docking bay for intercepted star freighters — but it’s about to explode! Or we’re Arctic animal rescuers, searching for crippled polar bears and embattled penguins. We administer first aid and restore habitats and sometimes, in the direst cases, tranquilize raging animals. And also poachers. We are acquainted, certainly, with the fact that polar bears and penguins exist on opposite poles and do not actually cohabitate — of course we are — but we don’t care. This is our thing, our rules. So we are Arctic pirates. Laying siege to disproportionately weaponed Russian whaling ships. Or . . .

My son pauses in his effort to strip pillows from every piece of furniture in the room. “Are we actually against the Russians?” he asks. “In real life?”

I filter this fairly straightforward question through a decades-old undergraduate degree in International Relations, a constantly shifting geopolitical milieu, an article I skimmed on CNN yesterday, and the capacity of a first grader to comprehend Vladimir Putin’s mercurial pugilism. “Kind of,” I say, “but not really.”

“So who should our enemy be?”

Glancing around at the chaos we’ve made of the basement — the denuded sofa, the upended table, the kidnapped comforter from the master bedroom, the Pottery Barn loveseat, once a designated “stretch gift” on our wedding registry, now flipped unceremoniously on its side — I imagine my wife returning from her shopping trip and mentally flash to an old Pogo comic strip: We have met the enemy and he is us.

“Robots,” I reply. Because robots are our standard go-to bloodless enemy.

But it’s too late; he’s already moved on. Now we’re dinosaur hunters, tracking the elusive Albino Triceratops. None of which changes the fact that we still need a base. Or a ship. Or a super-secret impenetrable fort. Which is what we’re currently constructing.

We are good at this, almost unfairly so. We are virtuosos with blankets and chairbacks. Master builders with misappropriated furniture. The basement is our canvas, and we are painting forts. Past success emboldens us, memorable breakthroughs like the Endless Tunnel of Doom or the Sofa Sectional Spy Tower having rendered us brash architects, irresponsible engineers who fail to apply even the basic laws of physics. Or gravity. Or common sense. We stack and remove pillows like Jenga players on speed, barely pausing to confirm the balance. We swap roofs for walls, tables for chairs, couch cushions for throw pillows. Displaying, throughout, an uncanny, almost innate, sense of spatial relationship.

“What about a plank?” my son says, piratical again. “For sending scurvy dogs down to Davey Jones’ Locker Room?”

“It’s just Locker,” I say, swiping my wife’s rolled-up yoga mat.

We unfurl it from the starboard side of the sofa, take turns teetering along its purple length. Shove each other off balance. Enact competing death-throe gyrations that require, suddenly, an elaborate scoring system. Three turns each, no repeats, points for pretend falling, pretend sinking and most realistic splash sound. He wins, but the outcome remains under protest. Still, the yoga mat is a perfect pirate plank, until it becomes a solar panel on a space station. We fashion paper towel rolls into periscopes, Legos into land mines, something from IKEA called a Sundvik into a secret trapdoor. Constantly tinkering, rotating and rearranging and dismantling and replacing. Barreling inexorably toward that moment when we can crawl inside, draw a loose sheet across the entrance, recline and appreciate the genius of our created space.

Marvel at the unexpected roominess of it all.

We might lie there a moment, hearts loud, breathing light. Shoulders grazing as we settle into the alcove, feet not quite fitting, each of us sensing the fragility of this space we inhabit. Not the fort, which we know is indestructible, but the moment. The privileged evanescence of a completed task not yet ruined, perfection untouched by entropy. Our mutual stillness will acknowledge this, father and son intuitively grasping the weight of it all. Or he’ll sit up, elbow my jaw in a scramble for the Nerf gun and shriek that dragons are attacking. That’s what usually happens. But sometimes there’s a bit of quiet.

If it’s the dragons, or the enemy robots, or a squadron of parachuting Velociraptors, or pretty much anything at all, it’s time for a Mission. I kind of hate this part. It typically involves gearing up with forgotten Halloween items from the costume box, some stuff stolen from the kitchen, a flashlight he borrowed months ago and never returned, and a bunch of things that used to belong to board games. Plus, more crawling and jostling than I’d prefer. Which is why I tend to allow one — at most, two — of the Missions to unfold before inserting a well-timed Sleep Break. That’s when I wriggle from the fort, shout Cover me! — so he thinks we’re doing another Mission — and beeline for the light switch at the bottom of the stairs. Then I flip it off.

“Nightfall,” I announce. “Even heroes need sleep.” Then we retire to the slender bedrooms we amended to the fort — him stretching out languidly, me curling fetally — and we see how long I can make nighttime last. “On this planet,” I might claim, “the sun is more distant and also collapsing, and nights last twice as long as days.” To which he’ll retort that we’re nocturnal or that we have top-secret echolocation powers, which leaves me simultaneously cursing the Animal Planet channel and alleging that echolocation fades as you get older. Just ask the bats.

“Are you older?” he asks.

It’s an easier question than most of the ones he poses, but when I attempt an answer the words lodge in my throat. Because the fort is so many things: pirate ship, space cruiser, Arctic basecamp. It keeps changing, morphing to our whims, becoming whatever we need it to be. Maybe it’s a Mars lander. A tank or a teepee. Maybe it’s a time machine. I say this out loud: “Now it’s a time machine.” It isn’t, he whines, because he still wants it to be a base, but it’s too late. For me, it’s a time machine.

Because inside this fort, the years come unhinged. I’m 7 again, or 8. And Tommy and Bobby and Joey and Brian are all in here, too. It’s a Rebel outpost and the Imperial walkers are closing in. Or it’s a cave in the Land of the Lost, and the Sleestaks are hunting us. Or we’re Bionic Boys with bionic limbs, and this is our secret headquarters. It’s the fort we built in our backyard in 1978, stringing Star Wars sheets from the clothesline, and in our closet in 1982, barricading the door with boxes, and in the woods in 1984, convinced we were masters of jungle camouflage. It’s every discarded refrigerator box we ever carved into a castle, every blanket we suspended from our battered bunk beds, every abandoned pallet we repurposed as a roof.

Long before the inevitable world came flooding in, the world of college loans and mortgage rates, voicemails and conference calls, before we became the people we’ve become — attorneys and teachers and marketing executives — we were pirates. And every fort we built, every sovereign space we carved into existence, became the thing we needed most: a temporary stay against the wider world. A thin barrier between the banal and our own boundless imaginations. The privileged place where we learned to tell stories to ourselves, about ourselves, woven into this world.

But forts, it turns out, are more than story starters. They are story hatcheries. Story sanctuaries. Not nouns, but verbs. With beating hearts and memories. They remember us, long after we’ve forgotten them. And sometimes, years later, they deliver us back to ourselves.

My son’s question still hangs in the air between our folded bodies.

Are you older?

In the darkness, my fingertips find a plastic dinosaur, a pair of binoculars, his elbow. And then the thing I’m looking for, another thing forgotten and returned.

“Cover me,” I whisper, taking up the flashlight.

David Devine lives and writes in Portland, Oregon.