The year 1939 had been rude to Richard Sullivan. A sweet-tempered and longsuffering professor of English and creative writing at Notre Dame, Sullivan ’30 maintained an active typewriter and soaring literary aspirations. Nine years out from his own graduation, he’d managed to publish a few poems and short stories in magazines like Scribner’s and had even broken into the ranks of Atlantic Monthly contributors, but the shine from such success was fading beneath a thickening stack of rejection slips — each one preserved in Sullivan’s papers in the University of Notre Dame Archives.

British Library

British Library

Mildred Boie, an editor at the elite Boston literary journal, was a master of the tart, one-line dismissal, and from May to December Sullivan received about one cutting rebuff from her a month.

“Dear Mr. Sullivan: ‘THE BEGGARS’ is sharp and effective, but not very appealing, and haven’t we seen it before?”

“Dear Mr. Sullivan: ‘The Intruder’ . . . impressed me very much, but we just don’t think in this crowded season it is a ‘must.’”

“Dear Mr. Sullivan: ‘Uncle Steve and the Pigeons’ is amusing, but too long drawn out.”

By the time the writer set his pen and notebook aside to celebrate Christmas Eve with his wife and two young daughters, dejection had wrung everything out of him but his faith and sense of humor. “Behind all my writing is the idea that life is a vale of tears,” Sullivan mused in his journal. “Maybe this is why I publish so little.”

At that moment, though, a small piece of good news was on its way: a contract from The Dramatic Publishing Co. of Chicago, laying out terms for the publication of a one-act play from which Sullivan had drawn a measure of reassurance (and modest royalties) for years.

He’d written “Our Lady’s Tumbler” in the fall of 1930 while beginning graduate studies in the drama school at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, designing costumes for its production of Oliver Twist and, like all of his Notre Dame classmates, hoping he could ride out the lingering recession that had hit during their senior year. In 1933, he’d received his first request to produce the play. By the time the Chicago firm expressed its interest in 1939, Sullivan could say it had been performed “with fair success by several community or university groups” as far away as Montana and was listed in the Federal Theatre Project catalog.

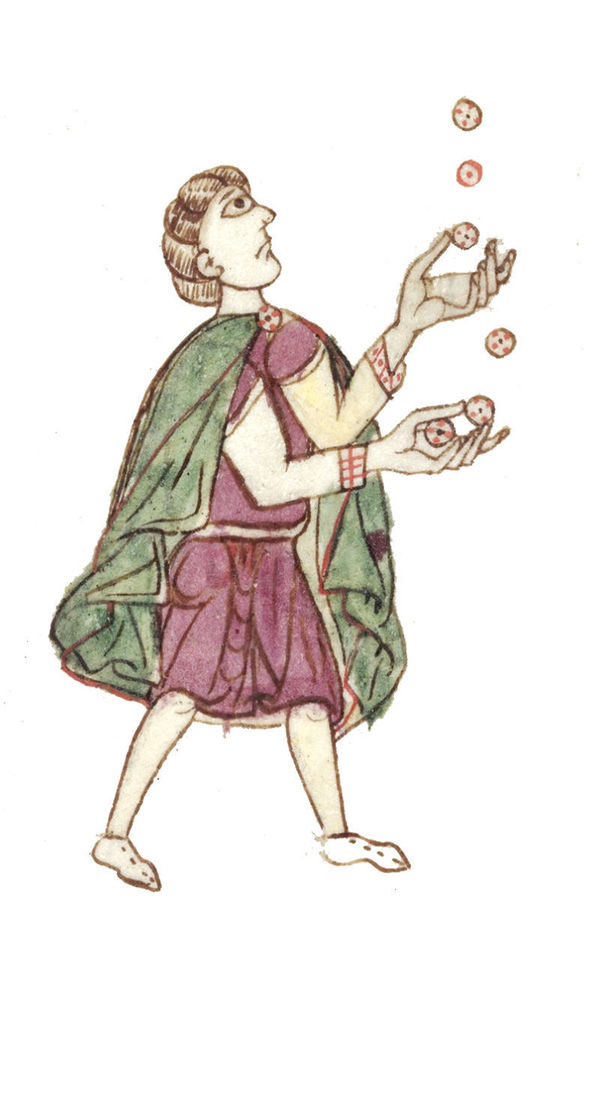

The only known image of the juggler from the MIddle Ages is this miniature from a manuscript produced before 1268. (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ms arsenal 3516, fol. 127r.)

The only known image of the juggler from the MIddle Ages is this miniature from a manuscript produced before 1268. (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ms arsenal 3516, fol. 127r.)

Sullivan’s inspiration was a 13th century French poem commonly called “Le Jongleur de Notre Dame,” which he’d discovered in an Everyman’s Library edition of medieval French verse. He would have known that a jongleur was a wandering acrobat, musician, juggler and comedian, and he’d have known that popular versions of the tale had inspired Notre Dame students to create the University’s first student-run humor magazine, The Juggler, in 1919 — and marching band director Joseph Casasanta ’23 to form a big-band dance orchestra called The Jugglers in 1927.

What Sullivan almost certainly didn’t know was that in 1910 the novelist D.H. Lawrence had read the same Everyman’s Library translation at his mother’s bedside as she lay dying of cancer. (“It is rich,” Lawrence later wrote to a friend. “It is a nonesuch.”) Or that Wallace Stevens, yet unknown as a poet, had told his fiancée the story in a 1908 letter, trying to cheer her up. Or that, months before the first performance of Sullivan’s stage version, Charlie Chaplin had worked the tale into a skit he performed privately for friends while contemplating its merits as his next silent feature. (Chaplin soon made Modern Times instead.)

Though the story of the tumbler, its title often translated as “The Juggler of Notre Dame,” had already made an impressive mark on his alma mater, it’s unlikely that Sullivan knew much at all about the cultural phenomenon surrounding it. By the time he wrote his play — which, he felt, was less an adaptation “than an original work based on legendary material” — the tale had already been retold in thousands of homilies spanning centuries; in landmark works of medieval scholarship and in the pages of a major daily newspaper; in handmade art books and mass-market paperbacks; in a major French opera and in graphic design, magazine illustrations, art deco posters and paintings.

Fast-forward 80 years and today we may add umpteen beautifully rendered books in the children’s literatures of at least a dozen languages, as well as radio plays, Christmastime television specials, another two operas and a ballet. At midcentury, the juggler was especially popular in the United States, part of a national nostalgia for all things Middle Ages.

In essence, here’s the story: A simple, devout, illiterate but skillful street performer renounces his worldly art and enters a monastery. There he finds he is unprepared to pray, chant, write, cook, sculpt, paint, bake or brew — any of the things the other monks do to express their devotion to God and the Blessed Mother. “And so,” as Stevens phrased it for his bride-to-be, “when no one was looking, he did his few tricks and turned a somersault; and thereupon, Our Lady, being much pleased by his simplicity, smiled upon him, as she had never smiled on any monk before.”

The details, even the juggler or tumbler’s name — he’s been called Barnaby, Jean, Rene, Giovanni, Wat and Cantalbert, among others — change from version to version, but in most the Virgin’s “smile” takes form as a miracle, a statue of Mary that comes to life in a crypt chapel to wipe the brow of the dying jongleur, humbling his brother monks who had spied on his private performances and condemned them.

The man who would connect all these dots to a Nobel Prize-winning French author, whose collected works were later banned by the Catholic Church, and to the extraordinary Marian sensibility and literary hiving on display at a liberal arts college in northern Indiana — is Jan Ziolkowski, a Harvard professor of medieval Latin.

Last fall, Ziolkowski published the final segment of his surprisingly accessible and fascinating six-volume cultural history of the story, The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity, available online and for free through Open Book Publishers. He also curated a one-time exhibit of the stories and artifacts he gathered during 15 years of scholarship — it ran for five months in the museum of Dumbarton Oaks, a Harvard research library he directs in Washington, D.C.

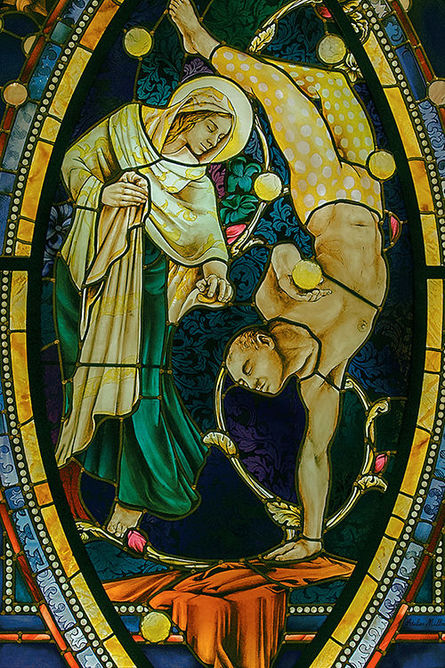

“Juggling the Middle Ages” featured scholarly lectures by fellow humanists as well as gallery talks by featured artists like R.O. Blechman, the New Yorker illustrator and graphic novelist, and the prolific children’s book author Tomie dePaola, both of whom have produced commercially successful versions. Young artists from the Washington National Opera sang arias from French composer Jules Massenet’s 1902 opera, Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame. And Ziolkowski commissioned Jeff Miller, an old friend from his Princeton days who leads a noted Paris atelier of stained glass, to create the world’s first depiction of the inspiring but likely fictional Marian miracle in that distinctively French — and medieval — medium.

Notre Dame’s Richard Sullivan, Ziolkowski says, is but one of hundreds of writers, composers, entertainers and graphic and performing artists who have kept the story’s ball in the air over the past 125 years. Like Sullivan, most of them seem to have been unaware of each other, practically regarding their encounter with the legend as “their own discovery.” And yet, the scholar figures, while remaining “hidden in plain sight,” the miracle of the juggler’s humble devotion may have been told and retold in more media and by more people than anything outside of the Bible, Homer and Grimm’s Fairy Tales.

Manuscripts are the medievals’ primary means of communicating with us, and the first known record of the juggler’s illicit performances in the Cistercian abbey at Clairvaux is an anonymous, 684-line poem in rhyming couplets of “Picard-flavored medieval French” that dates to the 1230s. Fifty years later, an anecdote appeared in a Latin tome from which priests would have cribbed stories for their homilies. Did an oral version predate these documents? We don’t know, Ziolkowski says.

Were they based on real events? Such tales were presented as true and would likely have been understood as such, but whether any element of this story — the juggler’s renunciation of the world, his conflict with his brother monks, the gymnastic floor routine in the chapel, the miracle of the Virgin — actually took place, Ziolkowski writes, “is beside the point.”

Marian spirituality reached a peak in the 13th century. What mattered for believers was that the story was plausible, and that it could inspire anything from penitence to joy, depending on how it was told. If, as the story suggests, Mary could smile on the humble devotion of one whose gains were ill-gotten, who stripped to his skivvies in public merely to enable his stunts, who performed in alehouses, whose jestering mocked authority and convention, who stood outside the social order by traveling from town to town to make his fortune and could readily be suspected of whoring and thieving all along his merry way . . . well, then, might there not be hope for the rest of us?

The story flourished in verse and in preaching for a few hundred years. Then came the Reformation, when, Ziolkowski notes, our tumbler performed “a centuries-long disappearing act.” Protestants generally frowned on monks, pilgrimages, saints, miracle legends, religious images and Marian piety. Catholics had grown uncomfortable with alternative forms of prayer and with individual consciences behaving in defiance of mores and institutional authority.

But times change. And when the tumbler reawakened in 1873 in the hands of philologists — those modern archaeologists of old languages and literatures — he found a world that wanted him again. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 had left the defeated French starved for champions and symbols of French cultural identity, while the ravages of industrialization nudged them to look backward for answers. The Middle Ages they saw was a gentle era of stability, community and religious harmony — far simpler, certainly, than their own times of cold scientific progress and William Blake’s “dark satanic mills.” Ziolkowski: “No matter how wildly inaccurate and fantastic we may find 19th-century understandings of the time, and regardless of how improbable we may deem the choice of antecedent to be, the Middle Ages presented themselves as the favored phase of history against which to measure, judge, understand, and shape modernity.”

In other words, “medieval became the new normal.” Pointed arches appeared on new buildings everywhere. Gargoyles erupted from Notre-Dame in Paris. Stained glass production skyrocketed. The French capital, already a publishing powerhouse, became a bibliopolis of Arts and Crafts books inspired by the illuminated productions of the old monasteries.

“Barnaby of Compiègne” — the juggler by his first modern name — soon took his place alongside St. Joan of Arc and the noble knight of The Song of Roland as a French national hero. Le Gaulois, a daily newspaper, had reintroduced him to the public in 1890 in a “Story for the Month of May,” Mary’s month, written by the poet and journalist Anatole France.

It is hard to imagine a more unlikely teller for the tale than France, whose adaptation fully revived the still-sleepy juggler. Educated in a Catholic school, the bookseller’s son took his cosmopolitan shots at the Church and at religious belief and practice throughout his career. He later became a vocal supporter of the Russian Revolution and the French Communist Party and, one year after winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1921, saw every letter of his life’s work listed on the Index of Forbidden Books. Yet in this one short story, though he depicts Barnaby as an artist struggling “like most of those who make a living from their talents,” France quotes Scripture several times without tincture of irony and depicts the monks, the monastery and the miracle itself with tenderness and respect.

Stained glass window created by Jeffrey Miller, Sarah Navasse and Jeremy Bourdois for Atelier Miller, Chartrettes, France, 2018. photograph by Jeremy Bourdois, 2018. courtesy Dumbarton Oaks.

Stained glass window created by Jeffrey Miller, Sarah Navasse and Jeremy Bourdois for Atelier Miller, Chartrettes, France, 2018. photograph by Jeremy Bourdois, 2018. courtesy Dumbarton Oaks.

Whatever France’s intentions, he liked the result enough to include it in an 1892 collection, Mother of Pearl, and its impact was vast. Translations began to appear, carrying the story abroad. Opera was next. Composer Jules Massenet “had been faulted for having been a ladies’ man, for being able to compose only when he was inspired by being in love with his divas,” Ziolkowski says. He needed a masculine libretto to shake that unwelcome reputation. So, “to show everybody he went off and wrote an opera that had only men on the stage” (except for the statue of the Madonna, of course, which remained silent).

Massenet’s Jongleur debuted in 1902 to his accustomed commercial success. But the show would have lost the spotlight (and big profits) if not for an innovation at the hands of the one person whom Ziolkowski upholds as most responsible for making the juggler “a juggernaut in America.”

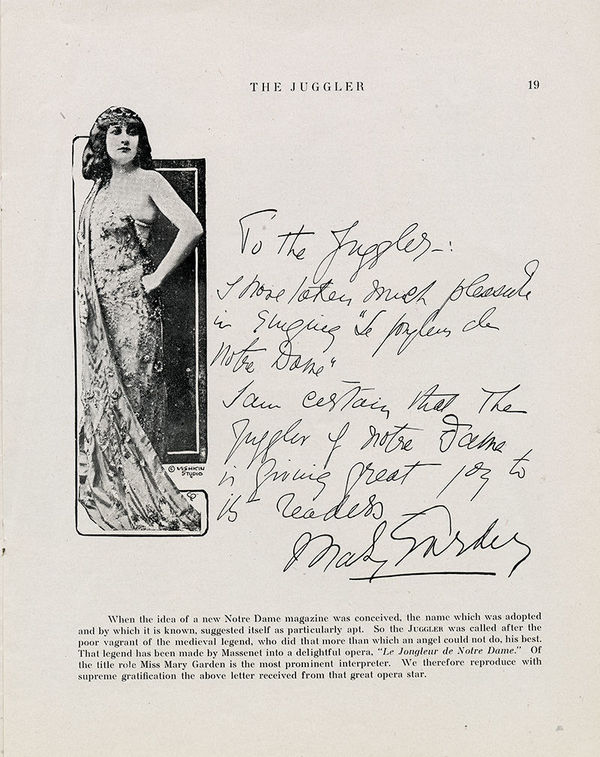

That person was Mary Garden, a rock star of the turn-of-the-century opera stage, a Scottish-born singer and actress who in New York and Chicago performed the role of “Jean” and who would continue to play the role before packed houses until her retirement in 1931. The sultry prima donna whose name conjures images of white statues in prim parish prayer enclosures is the soul who personally escorted the juggler to the University of Notre Dame.

The Gothic Revival in the United States didn’t stop with the art and architecture that gave us cathedralesque skyscrapers and the historic cores of who-knows-how-many college campuses. Mary made a comeback, too. After the French Revolution, the 19th century delivered a resurgent cult of the Virgin, highlighted by Pope Pius IX’s declaration of the Immaculate Conception and the Mother of God’s appearances to St. Bernadette in the grotto at Lourdes, France.

In America, Mary was a potent symbol of Catholic courage in the face of nativist oppressions, but she also transcended boundaries of language and culture between Catholics of different ethnicities. Shrines to her became destinations for pilgrimages made by people who held out slender hope of seeing their homelands again.

Father Edward Sorin, CSC, embodied this Marian zeal. Decades before European scholars unearthed the juggler’s tale, Sorin was cartwheeling around the Indiana backcountry, giving everything he had to act on her behalf and build a University in her honor. Ziolkowski notes that Sorin began to erect outdoor altars, chapels and replicas of Marian sites in Europe almost as soon as he arrived. In 1865, he founded Ave Maria magazine, boldly “devoted to the honor of the Blessed Virgin.” Other research has turned up evidence of Lourdes shrines behind the Main Building long before the construction of the Grotto in 1896. And the gleaming 20-foot statue of the Immaculate Conception atop the Dome has given religiously inclined students a focal point for their own prayerful work and play since the 1880s.

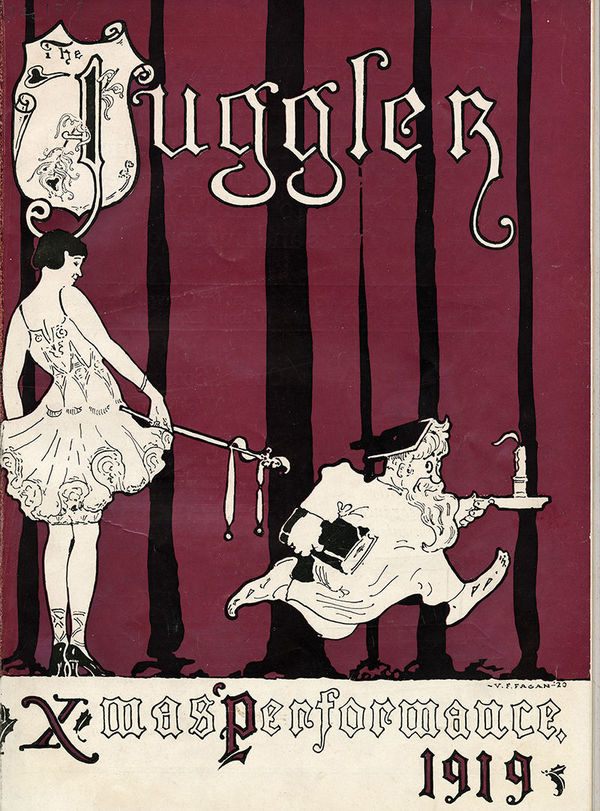

In the weeks before Christmas 1919, three Notre Dame fans of Mary — and of Mary Garden — “youths of irreproachable character and clean neck and ears” as the yearbook would describe them, tapped into a national trend as big as football and launched a college humor magazine from their rooms in Sorin Hall. Delmar J. “Pinky” Edmondson ’18, Andrew “Shrimp” Moynihan ’20 and Laurens “Moonshine” Cook ’20 were big men on campus. Edmondson, their ringleader, a former class president and editor-in-chief of the Dome and the Notre Dame Scholastic, had spent some months reporting for the New York Evening Post and was back at school to study law and theater. The three editors called their project The Juggler, sold advertising to South Bend businesses and had no trouble charging their peers 25 cents for a copy (about $4 today).

Edmondson wrote a “prologue” for the inaugural issue in the juggler’s voice and put performance of the Marian miracle (and the hope of future issues) in readers’ hands: “With the cooperation of students my ministrations will become permanent . . . without your help I shall ‘die aborning.’ Upon your encouragement my future must rest. But Hey-Ho! On with the show!”

Garden herself lent support, sending a publicity photo depicting her in an alluring evening gown and a congratulatory handwritten note:

“To the Juggler—:

I have taken much pleasure in singing ‘le Jongleur de Notre Dame’

I am certain that The Juggler of Notre Dame is giving great joy to its readers—

Mary Garden”

The cover artist for the first issue was an architecture student named Vincent Fagan ’20, who would leave several vastly more significant Gothic footprints around campus than his occasional sketches for the humor rag. It was Fagan, working alongside his former professor, Francis Kervick, who conceived Sacred Heart’s “God, Country, Notre Dame” east door to memorialize former students who had lost their lives in World War I (some of whom had been Fagan’s friends). Together the two designed Howard, Lyons and Morrissey Halls and worked with the renowned Boston architect Ralph Adams Cram on the drawings for South Dining Hall.

The inaugural cover, December 1919 (University of Notre Dame Archives)

The inaugural cover, December 1919 (University of Notre Dame Archives)

Mary Garden appeared to Notre Dame boys in the pages of their humor magazine. (University of Notre Dame Archives)

Mary Garden appeared to Notre Dame boys in the pages of their humor magazine. (University of Notre Dame Archives)

Fagan also provided lyrics for two of band director Joe Casasanta’s football marches, “Hike, Notre Dame” and “Down the Line.” His sister, Anita, married the musician, a link that makes the name Casasanta chose for his dance band, The Jugglers, less of a mystery.

Today The Juggler is a semiannual student prose, poetry and art magazine, and the story of its transformation is a choppy one. The original magazine passed from one set of student editors to the next until 1934, straining to entertain readers with “sparkling satire and wholesome wit” while steering clear of campus censors. Featuring puns, one-liners and he said/she said repartee, the typical preoccupations were alcohol, prohibition, South Bend girls and, eventually, the Depression. Example from April 1920: “Formerly hair tonic was good for shampoos; now it is also good for sham booze.”

“Unquestionably ours was the purest of the college comic magazines,” former editor Robert Gorman ’32 wrote in the South Bend Tribune in 1977. “‘It may not be funny but oh, boy, is it clean!’ was then a Juggler slogan among staff members — and probably a campus critique on the part of the student body.”

Somehow the constraints sharpened the product over time, and, not unlike the medieval jongleur, it suffered from its own hustle toward transcendence. By the time the Holy Cross fathers shuttered it for running up a $7,000 debt, The Juggler had won numerous national awards for content, design and overall quality. Years later, journalism professor Tom Stritch ’34 remembered it as “Notre Dame’s excellent humor magazine.”

In 1947, a new Juggler embraced the medieval legend in an entirely different mood, demonstrating the adaptable power of the supposedly simple story. Founding editor J.H. Johnston ’47 had fought in Europe with the 82nd Airborne. Assistant editor Charles Patterson ’44 had flown off aircraft carriers in the Pacific. Art editor Frank Duggan ’48 was a former Marine. The tone would be sober and serious, Johnston told a writer for The Notre Dame Scholastic, its high standards reflecting “the mark of the war years.” Stories and articles would “manifest a thoughtfulness and maturity that is not often found in college writing.

“In this connection the significance of the name Juggler should be noted,” the writer continued. “The old French legend of the jongleur, who juggled and leaped and tumbled before the statue of Our Lady (because it was the only art he knew), embodies the spirit of the Juggler. Students of Notre Dame, though they may not write with professional ease and brilliance, at least offer in their art the best that they have, for the honor of Our Lady.”

Whether every student who wrote for the new lit mag felt that way is unknown, and unlikely, but the Juggler prefaced every issue with its rendition of the aged yarn for at least a decade. Contributors included writers of future distinction such as Samuel Hazo ’49, the first poet laureate of Pennsylvania, who would feature the tumbler in a 1975 monologue (“I am God’s clown. From glee to grief I go”), William Pfaff ’49, a longtime columnist for the International Herald Tribune and Ken Woodward ’57, Newsweek’s religion editor for 38 years.

One last Notre Dame connection to the story is worth mentioning. Among the 10 mostly melodramatic radio productions Ziolkowski tracked down as having aired in the U.S. between 1940 and ’53, each with an original script, is one by Family Radio Theatre, a ministry of Father Patrick Peyton, CSC, ’37, the “Rosary Priest” recently declared venerable by the Church. Danny Thomas starred as Barnaby and hosted the show — famous for its motto, “the family that prays together, stays together” — on January 16, 1952.

Richard Sullivan described writing as “hard work requiring patience and idiotic perseverance.” Like the juggler, the devout Catholic and world-weary artist stuck with it. Sullivan published his first novel in 1942, adding at least four more and a collection of short stories over the next 17 years. He faithfully shipped book reviews to The New York Times and the Chicago Tribune, earning income he needed to keep his family afloat in light of his wife’s poor health. His best-remembered work is Notre Dame: The Story of a Great American University, a lyrical, nonfiction snapshot of campus life on the eve of the Hesburgh presidency, published in 1951.

Stritch’s appraisal of Sullivan’s “tasteful” teaching and “well-wrought novels” is best. “Somehow the note of wide popular approval escaped him. In a time when John O’Hara was setting the pace in fiction in the United States, Sullivan was only a little ways behind — a little less sharp, a little less energetic. Still,” Stritch wrote, “his work deserved greater success than it achieved.”

It’s natural to wonder — when Tony Curtis timed out from filming Some Like It Hot and Spartacus to create The Young Juggler in 1960, or when W.H. Auden and Edward Gorey teamed up on “The Ballad of Barnaby” as the libretto for an opera first published in The New York Review of Books — whether the Notre Dame professor thought back on his own “Brother Wat.” The year after Sullivan died in 1981, Disney found yet enough life in the story to produce its own made-for-TV version starring Merlin Olsen. Ziolkowski thinks these American creatives in particular “have now and again made the agony and the ecstasy of the jongleur the opener for conveying their own floundering as creators.” Aren’t we all jugglers in the end?

Since then, popular imagination of the Gothic has darkened (see Assassin’s Creed, Game of Thrones and the often-medieval aesthetics of death-metal bands and white supremacist groups for the most salient examples. Barnaby himself appears to be exiting stage left. Ziolkowski’s academic enthusiasm is one exception to these trends. For him, the questions posed by the original medieval poem endure.

“What makes for a suitable gift?” he asks. “What constitutes acceptable prayer? Does worship require words, or can there be a liturgy of movement, even dance or juggling? Can work be an expression of devotion?”

Might the juggler sprout fresh legs in an age of spiritual seeking, artistic self-expression and the diminished influence of hierarchy?

The warmhearted Harvard linguist who calls the juggler “his hero” pursued him for 15 years in part because he “wanted to demonstrate that humanistic research and artistic creation go hand in hand,” while bringing readers — and Dumbarton Oaks’ visitors — a little joy along the way.

“I really do look at it as a big ball in a gym, in one of those games where kids are told not to let it touch the floor. And it has almost touched the floor, and I dove, and I knocked it back up in the air,” he says. Now it’s someone else’s turn. “But I will admit that I would be very happy if I could come back posthumously, 50 years from now, and see that there had been an upward jag in its afterlife.”

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.