Author Norman Mailer described what occurred at the 1968 Democratic National Convention as “the siege of Chicago,” and that week of rage in late August 50 years ago produced political repercussions still reverberating today.

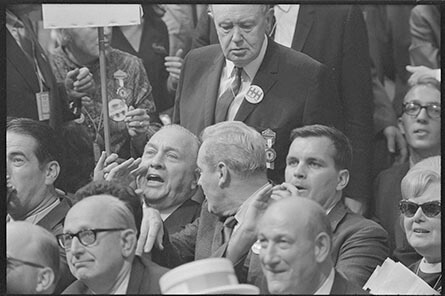

The scene inside the 1968 Democratic Convention. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The scene inside the 1968 Democratic Convention. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Have you ever asked yourself how the current nominating process of presidential candidates began and why Washington “outsiders” win the White House so often these days? In both cases, the roots of what’s happened in the past half-century extend back to those fateful — and bloody — days in the Windy City.

Five months before the convention and beleaguered by mounting criticism of the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson announced he wouldn’t seek re-election as president. That unexpected decision opened the door to a ferocious struggle over who would become the Democratic nominee for the fall campaign.

Three candidates emerged as contenders: Senators Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota and Robert F. Kennedy of New York, who faced off in four of the nation’s 15 primaries that year (with Kennedy winning three), and Johnson’s vice president, Hubert H. Humphrey, who joined the fray in April, opting to collect delegates without running in a single primary.

But tragedy struck in early June. Kennedy was shot and later died after delivering his victory speech in California, his most consequential triumph of his brief campaign for the nomination. RFK’s assassination, two months after Martin Luther King was killed, forced Americans to question where the nation was headed politically and morally.

Going into the party convention, Democrats faced a difficult but definite choice. They could support a strongly anti-war candidate (McCarthy) or the No. 2 figure of the Johnson administration (Humphrey), who’d sided with the president’s policy in Southeast Asia. (LBJ’s approval rating in August of ’68 was 35 percent, the lowest of his White House years.)

With battle lines clearly drawn, protestors against the war descended on Chicago in the thousands, far exceeding the delegates. One estimate put the number of law officials and troops on hand to try to keep the peace at 20,000.

From August 26 and for the next three days, while Democrats debated their platform and selected their ticket — Humphrey defeated McCarthy 1,759 votes to 601 — protests, both non-violent and otherwise, provided dissenting words and actions to traditional politics around Chicago.

Indeed, on August 28, as the delegate roll call nominating Humphrey took place inside the International Amphitheatre, law enforcement officers and demonstrators engaged in fierce combat in Grant Park and along South Michigan Avenue. Television networks faced the dilemma of broadcasting either the floor of the convention or the gory melees happening close by.

In the aftermath of the convention, two very different reports appeared. The first was a study by a government commission that classified the conduct of the Chicago officers in their confrontations with demonstrators as “a police riot.” The other was a party committee’s analysis criticizing a closed nominating process that allowed someone to be the party’s standard-bearer without competing for the nomination in contests involving voters instead of delegates.

What was called “the Commission on Party Structure and Delegate Selection” developed out of discussions initiated at the 1968 convention. The Commission stressed the importance of opening up the nomination process to more people in transparent ways. Citizen involvement, particularly through participation in primaries and caucuses, would replace old-style backroom bargaining by political insiders in what were commonly referred to as “smoke-filled rooms.”

In the Commission’s guidelines, this paragraph appears: “The 1968 Convention indicated no preference between primary, convention, and committee systems for choosing delegates. The Commission believes, however, that committee systems, by virtue of their indirect relationship to the delegate selection process, offer fewer guarantees for a full and meaningful opportunity to participate than the other systems.”

An immediate effect of the Commission's proposals was a proliferation of Democratic nominating contests in 1972. From the 15 primaries in 1968, the number almost doubled — to 28. Though the Republicans were somewhat slower in expanding the nominating process beyond party officials, the emphasis on openness and citizen selection eventually took hold nationwide within the two major parties.

The scene outside the 1968 Democratic Convention. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The scene outside the 1968 Democratic Convention. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

A critical year in this evolving process was 1976. Republicans had primary contests in 28 states that year, with President Gerald Ford battling Ronald Reagan, a former two-term California governor, all the way to the party's convention in Kansas City. Ford, ultimately, received the nomination with 1,187 delegates to Reagan's 1,070.

On the Democratic side, Jimmy Carter, a one-term Georgia governor, took on some 16 other hopefuls (of varying degrees of seriousness), and Democrats conducted 28 primaries, the same number as the Republicans. Carter dominated the delegate competition, and political analysts that year noted that a “candidate-centered” process had officially replaced a “party-centered” one, with the Georgian’s success described by one observer as the end point of “the old boss-dominated system.”

Early in the 1976 campaign, newspaper headlines kept asking a two-word question: “Jimmy Who?” But Carter’s triumph over Ford in the November general election started a significant trend in presidential history. The six presidents who preceded Carter were either Washington insiders (Harry Truman, John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford) or known as well-connected in the nation’s capital (Dwight Eisenhower). Carter was a bona fide outsider, with no experience in federal office and a total of just eight years in state government (four as a state senator and four as governor).

Interestingly, presidents following Carter included other Washington outsiders: Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump.

George H.W. Bush, with eight years as vice president and extensive service in appointed positions (CIA director, United Nations ambassador, etc.), certainly qualified as an insider; however, his election in 1988 was, in part, a referendum on Reagan’s record and interpreted by some pundits as “the Gipper’s third term.”

In 2008, Obama was a U.S. senator when he sought the White House. But he had completed less than four years of a six-year term and much of his time in the Senate was actually devoted to pursuing the Democratic presidential nomination.

Trump’s unexpected victory in 2016 was the apogee of outsider achievement on the presidential level. A candidate with no political, governmental, or military experience took on 16 contenders in the Republican nominating contests, many of whom were governors and senators, and the business tycoon/media celebrity prevailed in the fall against a former first lady, who was also a former U.S. senator as well as a former secretary of state: Hillary Clinton.

Clinton was by no means the first well-known insider to lose a White House race in the new, post-1968 political environment with its emphasis on openness and civic engagement from the nominating period through Election Day. Other identifiable insiders defeated for the presidency since party elders abandoned their smoky spaces included Walter Mondale in 1984; Bush, Sr., in 1992; Bob Dole in 1996; Al Gore in 2000; John Kerry in 2004 and John McCain in 2008. In each case, Washington expertise proved less important in most voters’ minds than the desire to place someone not associated with Washington at the head of the federal government.

What’s behind this dramatic shift from supporting, say, a senator like Kennedy, or three former vice presidents who had been senators previously: Truman, Johnson and Nixon? According to survey research, one of the first measurements of “trust” in federal government took place in 1958. Almost three-quarters of those surveyed (73 percent) responded that they trusted “the government in Washington always or most of the time.” The number rose to 77 percent, its peak, in 1964.

But then Vietnam, Watergate and the Iranian hostage crisis delivered such severe blows to the body politic that trust started to plummet — and just kept dropping. In 2011, after years of just a quarter to a third of citizens having trust, the percentage declined to a low of 15 percent.

Without trust, voters don’t have confidence so they look elsewhere—beyond Washington — for leadership in the White House. Make way for the outsiders.

The expanded influence of the primaries and caucuses has also had a definite impact on who would, ultimately, become president. Three incumbent chief executives — Ford, Carter and the elder Bush — faced strong challenges within their own parties (in 1976, 1980 and 1992 respectively), and they all lost in the general election.

By contrast, Reagan, Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama did not receive serious competition for re-nomination — and they won second terms. If Americans perceive that a president might be vulnerable politically, it signifies possible weakness — and voters never like to imagine weakness in a president.

Though primarily remembered for the violence between police and protesters, the 1968 Democratic Convention had dramatic and broader consequences on the American presidency. Citizens began to think more seriously about greater involvement in choosing White House candidates.

Both major parties opened up their nominating procedures in the wake of “the siege of Chicago,” and not long afterwards outsiders took up occupancy in the Oval Office, with U.S. politics decidedly different from the past.

Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor Emeritus of American Studies and Journalism at Notre Dame. He’s the author, most recently, of Fifty Years with Father Hesburgh: On and Off the Record (Notre Dame Press), which will be reissued this fall with a new afterword-chapter.