Illustration by Bett Norris

Illustration by Bett Norris

I’ve been taking Mendelssohn to the beach for many years now. There he waits for me, stored on an old iPod; I need only remember to charge it before I leave. I never forget.

Previous generations doubtless would have liked to enjoy Mendelssohn on the beach as well, and we can imagine with a smile what might have happened if they tried. Victorian women, fringed and bonneted, follow a procession of musicians who try in vain to shield their instruments from the slanting rain; a group of young men educated at Cambridge before the war wheel an old piano across the sands; a crofter, remembering a fragment of melody he heard on the radio, whistles while he scrambles over the rocks, only to have it lost in the wind.

The beach is indifferent to Mendelssohn — the waves will go on beating their hollow tune without him until, one day, no one remembers his music anymore, and the last grain of sand slips into the sea.

I have tried with varying success to carry Mendelssohn with me on many beaches: the pebbled shores of Lake Superior; the sunny cliffs of California; the long, sweeping dunes of Holland. But none can compete with the craggy west coast of Scotland. There and there alone is where Mendelssohn belongs.

Mendelssohn went to Scotland in 1829. The exact details of his journey escape me, but I am unwilling to turn to some reference book — even though one is glaring at me from my bookshelf — to assist my memory for fear of damaging the vision I’ve built in my mind. We are kindred spirits, I like to tell myself, and he sought on the barren outcrops of western Scotland, along with many of his brothers and sisters who were steeped in the writings of European Romanticism, what I seek there today: solitude, perhaps the sublime, the opportunity to wander across fog-mantled clifftops, to imagine old legends come to life, giants tossing rocks far out to sea, a corsair burying his plunder on the shore beneath, princes in rowboats escaping failed revolutions.

He journeyed first to Oban, a small fishing village that would soon transform itself, like many towns in Scotland, to cater to 19th-century tourists who trundled north along newly laid railway lines. Today the town still calls itself, without irony, the “Gateway to the Isles,” a name infused with such adventurous spirit that even to whisper it makes us young boys who dream of clambering aboard high-masted ships to cross the uncharted sea in search of gold and spice.

Mendelssohn’s voyage was probably not that exciting; he reported violent seasickness when he left Oban by boat. Still, the promise of the destination must have buoyed his spirits. He was going to Fingal’s Cave.

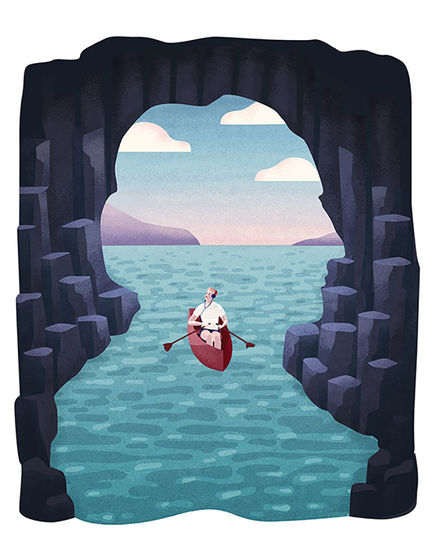

Wordsworth had gone to Fingal’s Cave. So had Keats. The painter J.M.W. Turner would go soon after Mendelssohn. Queen Victoria went in 1847, Tennyson in 1853. When they returned home, each of these distinguished men and women would attempt, in the medium that came most naturally, to sum up the experience of traveling to the remote island of Staffa to view a large cave formed of basalt columns. The “cathedral of the sea,” the poets called it. Turner’s painting shows us a few lonely gulls, a storm-tossed sea, an improbable flood of light pouring through the clouds to illuminate the cave’s entrance. It would take Mendelssohn several drafts before he was satisfied with the concert overture that eventually became known as The Hebrides. He wanted it to savor of “train oil and seagulls and salt fish,” rather than of the counterpoint of his formal education.

I, too, went to Fingal’s Cave, in 2014. I was fortunate that the journey was everything I had hoped it would be — waves and wind and that glorious mixture of cloud and sun that seems only to exist along the blustery shores of the north Atlantic. Our boat could barely approach the small jetty on Staffa, as it was whelmed by the heaving ocean every other minute. The other tourists hurried up the stairs to the top of the island to look for puffins; I made my way along the perilous cliff edge toward the cave. I would have to pause frequently to allow the water to recede as the waves flung themselves in my path, but soon enough I reached the cave’s mouth. I was greeted by what sounded like cannon fire, as swell after swell was forced into its far recesses. The basalt columns, often likened to organ pipes, threw the echoes back and forth; the pearly foam tossed up by the sea made the rocks glisten green, blue and pink. I cried, and then I slipped in my earbuds and let Mendelssohn work his magic on the scene.

I first sat with Mendelssohn on the beach in 2010 on a family trip to Scotland. We had crossed the sea to the Isle of Skye, our ears brimming with the silly fables that guides dressed in kilts love to tell tourists. I didn’t care about fairies or the old siren princess who would lure sailors to their deaths. I simply wanted to walk on the beach and wait in the approaching darkness for the lighthouse to be lit across the bay. Having played Mendelssohn’s overture with the college symphony the year before, I thought he would be good company in this moment. By the next afternoon I had fallen in love with Mendelssohn’s Scotland. It was a gusty but brilliantly sunny day, and the bus had dropped us off to putter around the northern tip of Skye. I was joined again by Mendelssohn, and I unexpectedly found deep, secure peace in that blend of cliff, sea, cloud and sky — sheep dotting the hillside, fishing boats bobbing in the vast expanse of blue, the gate on the ruin banging in the wind.

My life was subject to personal and professional upheavals that effectively sundered past from present. The business of living became increasingly stressful, and every couple of years I would turn to my former self and find him unrecognizable.

I can boast no Scottish ancestry. This was no voyage of self-discovery. Perhaps I had simply read too many novels; like many 19th-century tourists, I had run to Scotland clutching a volume of Walter Scott under my arm. Whatever the cause of my fascination, in subsequent years I would return to Scotland as often as I could, usually alone. In midwinter I scrambled along the coast of Harris, foolishly treading off the path and nearly plunging to my death. I went to Fair Isle to sit in a lighthouse. In Orkney I crawled into half a dozen Neolithic tombs. I chased ponies in Shetland and the next year took up my staff to walk to the end of the Kintyre peninsula. I cycled the length of the Outer Hebrides.

Outside of my journeys to Scotland, my life was subject to personal and professional upheavals that effectively sundered past from present. The business of living became increasingly stressful, and every couple of years I would turn to my former self and find him unrecognizable. Memories of childhood are dim and uneven, my college years a patchy blur. Changes have been swift and intense, and the resulting personal growth has alienated me from friends and family. My life now resembles nothing I could have imagined growing up in northern Minnesota, and the rapidly expanding vistas of experience have been both vitalizing and disorienting.

- 6th Annual Young Alumni Essay Contest

- 1st Place: “Mendelssohn on the beach," Edward Jacobson '13

- 2nd Place: “Rodent," Gretel Kauffman '16

- 2nd Place: “I just happened to be there," Rachel Plassmeyer Bené '10

- HM: "Playspace," Laura Andrews '10

- HM: "Wherever we are," Jacqueline Cassidy '15, '16MSM

- HM: "A love letter to the internet," Johanna Kirsch Wilson '10

- HM: "Summer magic," Victoria McQuarrie '12

- HM: "Father-daughter time," Stephanie Nguyen '09

Recently I wondered if I was not going to Scotland out of routine. The landscape had become stale, marred by my overexposure. I was no longer as emotionally sensitive as I once was. I could recognize beauty spreading all around me, but it did not overwhelm me as it once did. I returned to Skye last fall, this time with some friends. The mood was tense in the car; we’d had a fight that morning. It’s a long drive when nobody wants to talk. When we arrived at the house I slammed the door and headed down to the beach, asking myself why I continued with the bother and expense of dragging myself up here year after year. I kicked at some stones, stared out at the gray sea, and out of habit reached into my pocket for the old iPod.

There are so few constants in our lives nowadays, but in that moment all of the old memories of Scotland burst across the floor of my mind. The color of that sea, of that tuft of grass, of that cloud; the smell of that air, of that peaty earth; the biting of that wind — past and present collapsed, and I could recall with crystalline intensity how much this place has meant to me. At the melancholic clarinet duet near the end of the overture, I felt my eyes moisten for the first time in years. What a joy it is to walk on the beach.

Edward Jacobson’s essay won first place in this magazine’s 2018 Young Alumni Essay Contest. A doctoral candidate in musicology at the University of California, Berkeley, Jacobson is completing a dissertation on opera and literature in early 19th-century Italy. He lives in Amsterdam. Contact him at edward.jacobson@berkeley.edu.