The summer of 1960 was our last summer together, and golf was our passion. Jim Egan, Notre Dame class of 1964, one of my best friends in high school, and I hauled our clubs around the New Jersey course, playing the same holes day after day, knowing all the bunkers, trees, hilly lies, every hidden and obvious obstruction that makes a golf course a never-ending challenge.

It seems like a long time ago, but not so long ago that I can’t remember the two of us duking it out on the 16th hole of the Plainfield Country Club for the Junior Club Championship that summer.

I must have had a good day on the course, because I remember the match pretty much being over after the long par-5 16th hole. It seemed then like the longest hole in all of golf. The pin appeared thousands of yards away from the tee, the right side of the fairway just waiting with all those trees to suck up a slice. At the end of that monster, I went three up on Jim. With two holes remaining, the match was virtually finished. We could have walked back to the clubhouse, but I remember playing out the 17th and 18th holes. Whatever the score, we liked to play the game.

We parted ways after that summer. He went to Notre Dame, and I sent my trunk by railroad express to Durham, North Carolina, where I started at Duke. After graduation, Jim went into the Marines and I into the Navy. It was something our generation did. Our innocence certainly didn’t prepare us for how final that parting would be. Vietnam was just around the corner, but we were pretty clueless as to what being “in the service” might mean.

Having graduated toward the bottom of my NROTC class, I was not assigned to the sexy Navy—the Navy made up of aircraft carriers, hotshot pilots, nuclear submarines or even the dashing destroyers. I went to USS Donner (a Landing Ship Dock or LSD-20), part of the amphibious fleet called the “Gator Navy.” We carried regular Marines, reconnaissance Marines, Navy Underwater Demolition Teams (predecessors to the famous SEALS of today), and other shock troops and special forces.

The letter from Jim

That was 40 years ago or more. I really hadn’t thought much about Jim Egan until about 10 years ago when I found a letter in an old cardboard box. I was in the carport, months after a family move, contemplating unopened boxes, some sealed long ago with tape now yellowed and frayed. I sat down by one and pulled off the old yellow tape. How long ago had I packed it? Where?

I carefully unearthed tokens of my past like an archaeologist. Tenderly I pulled out old college notebooks; my NROTC insignia, preserved in a clear plastic folder; letters from girls I had long forgotten about.

When the letter from Jim Egan came into my view, I recognized it instantly. It was faded but still readable, dated 9 October 1965, Saturday, Ky Xuan, an island, as Jim described it, “northwest of the airfield [Chu Lai].” He added, “You can see it in Time maps, etc.—it looks roughly like the continent of Africa upside down—it is right at the mouth of a river. This is now our very own South Pacific island a la Viet Nam.

“Thanks a lot for writing and filling me in on your travels,” he had written. “I came over here from Oki [Okinawa] on the Gunston Hall (LSD-5 I believe), and I think she’s due for the melting pot after this tour.”

He described his job laconically. I had written him earlier, on August 22, guessing that he was in artillery. So was I, in a fashion—weapons officer on a Navy ship. Jim, however, was out there with the grunts. “You guessed right about my being in artillery,” he wrote. “When I first arrived I was one of the officers in a general support battery of 155-mm howitzers."

That fall of 1965, when Jim wrote me from his island in Vietnam, I was at Gitmo—Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. We both had been in service for about a year. My diary entry for 6 November 1965, a month or so after Jim’s letter, was almost as laconic as that letter: “Back in Little Creek [Virginia, homeport of the Atlantic Amphibious Fleet] after a month of Guantanamo Bay, Port-au-Prince, and the transit to and fro. The only memorable recollection from Gitmo is the heat, the perspiration, the constant bath of sweat I lived in."

Gitmo was usually the first stop after a ship underwent extensive repairs and refitting. My ship, the Donner, spent three months in the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard in the summer of 1965. By definition, we were due for “refresher” training to get the crew up to snuff.

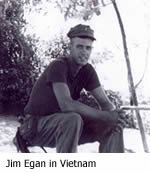

How did Jim get on that island at the mouth of the river in Vietnam anyhow? Only years later, with the help of others, did some of the pieces begin to appear. From the faded clippings in the Notre Dame archives, Jim emerges as president of the Glee Club, and his picture in the yearbook is of a handsome young man looking out at the world with quiet confidence.

There’s also the engagement picture of a pretty girl, Carole Barskis, dated January 1965. Carole was a graduate of Saint Mary’s College and was teaching at the International School of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo. An adventurous girl? One with a gift for teaching? Perhaps with a calling of some sort? She and Jim were to be married that summer. They had met on election night 1963 at Notre Dame, where both had volunteered at the polls. By the time they graduated in June 1964, they knew they wanted to spend the rest of their lives together. Jim, who had done well at the Marine officers’ training base at Quantico, Virginia, and had a choice of duty stations, planned on living in Hawaii after the wedding, expecting to be stationed there for three years.

But the events of the preceding summer were building up like a seasonal thunderstorm. While I flew from McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey to the Mediterranean to join my ship for the first time, and Jim was making the grade at Quantico’s boot camp, American destroyers tangled with North Vietnamese PT boats in the Gulf of Tonkin, far, far away.

The war widens

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident has become the famous landmark on the road to increasing U.S. participation in Vietnam. On August 2, 1964, North Vietnamese PT boats attacked a U.S. destroyer that was off the North Vietnamese coast but in international waters. The ship, which had been supplying intelligence but supposedly not military support for South Vietnam, suffered almost no damage. Two days later, another U.S. destroyer reportedly was attacked, although information obtained years later revealed that the “attack” was probably a false radar reading.

That controversial incident provided then-President Lyndon B. Johnson with the rationale to widen the war against the North Vietnamese and their guerrilla allies in South Vietnam, the Viet Cong, in his attempt to prevent communism from spreading further into Southeast Asia. This was Johnson’s application of the “domino theory”: If one state or people fell to the communists, then adjacent states would be susceptible.

I don’t know if Jim was any more aware than I was of the domino theory and how it would play out in our lives. In March 1965, a few months after Jim and Carole were engaged, two Battalion Landing Teams of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade landed ashore just north of Da Nang to protect that U.S. air base. The Marines had been deployed from Okinawa and were the first regular U.S. forces in Vietnam. This was the true beginning of the Vietnam War for Americans, although “advisers” and air support had been in place for a number of years.

Jim must have seen the action coming. He and his unit were ordered to Okinawa and then to Vietnam aboard the old Gunston Hall that he’d described to me in his letter. The marriage and honeymoon would have to wait.

Shortly after the first Marines were put ashore at Da Nang, the U.S. military decided to build a second airfield about 60 miles to its southeast. The site chosen was given the name Chu Lai. That airfield was built quickly. By the time the first Marine A-4 Skyhawks touched down on the 4,000-foot runway, Jim was there, having come ashore on May 19.

Jim was an artillery officer and later became a forward observer, temporarily attached to a unit of the ARVN (the South Vietnamese Army) to offer artillery support for the Marines when needed. As a Marine officer, he was with Delta Company, 1st Battalion, 4th Marines. His battalion defended the north end of the airfield and patrolled about five miles out in a sector northwest of the airfield. He was soon in combat.

“I went on almost all the platoon, company and battalion-sized operations,” Jim wrote me in that October 1965 letter. “About the only one I missed 2 men were killed and four injured.” Jim added, with a bit of battlefield humor, “3 of them now have 4 legs between them—and one of the dead was a platoon leader named Jim Mitchell who was really great and a top notch Marine.

“I’ve been pretty lucky so far,” he continued. “In fact, no one’s been seriously hurt while I’ve been out. We’ve been lucky though—we’ve had mines and booby traps fail to go off and have only had one man hit by rifle fire (in the foot).”

Morale was high at this time. It comes through clearly in Jim’s letter.

“The V.C. [Viet Cong] are very poor shots and usually fire from too far away—mainly because they’re afraid of Marines. They have good reason to be—the other night one of our squad patrols of about 8 men was ambushed and killed 2 V.C. and wounded 3 others. We didn’t have any casualties, which was really good—there should have been some.” That was the young Marine officer, learning on the battlefield.

Life in Vietnam

Then Jim told me about life on his own Shangri-La, the island called Ky Xuan. “We are doing civil affairs work (medical, etc.) and patrolling etc. The local V.C. Chamber of Commerce stopped by to throw a few rounds at us the first few nights, but I think they’ve been somewhat discouraged now since they have been quite unsuccessful to say the least."

I read back through my journal from the same period, and uncovered my own military experience with civil affairs. In my case it was a visit to Port au Prince, Haiti, sometime in October 1965, almost exactly the same time frame in which Jim wrote me.

“The whole of Haiti,” I wrote then, “excluding a minuscular segment, is poverty-stricken beyond belief. We brought some people-to-people stuff in [humanitarian assistance in today’s lingo] but the dent it made was nil at best.”

Later one of Jim’s Marine friends wrote me that “the captain of the company nicknamed [the Ky Xuan island] ‘camp gaf.’ If the brass asked what gaf meant it was ‘gain a friend,’ but to the troops it was ‘give a f_.‘” I don’t know if Jim was as cynical as most, but I think we both realized what little impression we were making, he on the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese, and me on the Third World poverty of Haiti.

“From our clean decks and spotless living quarters,” I continued in my journal, “we could see the men and women and children wander out of their thatched straw and clapboard hovels, to urinate and defecate with their animals in the yards, porches or whatever the squalid open spaces around their shelters can be called.”

Then, like Jim, I seemed to be at a remove. “It impressed my mind but found very little sympathy from my heart. Perhaps my own circumstances prevented me from reaching out. I don’t know.”

In his letter, Jim soon returned to quotidian life on his island. “We are resupplied by chopper and get hot chow twice a day.” He also was not without the amenities. “In our tent we are wired for stereo. One of my radio operators fixed up a portable stereo with one extra speaker, and a speaker from a radio.” Jim added, parenthetically, “(Kingston Trio ‘With Her Head Tucked Underneath Her Arm’ on now.)”

So life wasn’t so bad. Or maybe that was just Jim’s way of looking at it. He saw the proverbial glass half-full, not half-empty. As I write this, I again see why we had become friends. “Things are going OK here, I think, and they seem to be going well all over here.” Already the anti-war movement was cranking up at home, and Jim could read as well as I could. So he added “I think” things are going well.

“I guess the critics are slowly realizing their mistakes—now that we are being successful, everyone is starting to think it was a good idea.”

We parted ways on that, but there is plenty of room in a good friendship for disagreements. I thought it was a lousy war, but I wasn’t there. Jim was. He saw it from the ground, in place. Maybe he was right.

I would have my opportunity to participate in the war in 1966, but that’s another story.

Jim disappears

Jim’s war ended on the night of January 21, 1966. He was out on patrol when his group was ambushed. Scattered by the attack, the troopers regrouped at a designated position. Jim never showed up. They searched for him until nightfall. They searched the next day for him. A few days later they searched from the air, and a team of 50 Marines was sent in to comb the area.

Leroy Blessing, the first sergeant of an artillery battery based at Chu Lai and a friend of Jim’s, recalled: “It had been raining almost continuously, around the clock. It was foggy, hazy; visibility was limited, and they decided to end patrolling for the day.” Then they were attacked, but when the patrol reassembled, Jim was missing. “We don’t know what happened to him,” said Blessing. One of the patrol members thought he remembered Jim grabbing his stomach as if he had been hit. When they went back over the ground, they found no blood, no body. Only his pencil-size map light, used to read his maps at night to coordinate artillery strikes, was found.

Jim passed into that limbo of war reserved for those who could not be accounted for in any other way: MIA, missing in action.

The news devastated his parents and his sister, Joanne, who was 13 when her brother disappeared in the haze of war. His mother later went to Vietnam three times to find her lost son.

Over the years, the old images of a young Jim slowly replaced the memory of the living person. In May 1971, Jim’s picture, in his formal Marine blue officer’s tunic, appeared in Reader’s Digest, along with 49 other young Americans, each representing a state, as MIA or a prisoner of war.

Following Jim’s disappearance, his mom wrote him weekly, hoping the letters would reach a wounded son taken prisoner. None were answered. She became one of the leaders of the New Jersey chapter of the National League of Families of Prisoners and Missing in South East Asia and met in 1971 with the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, a fellow named George H.W. Bush, to present a petition signed by thousands calling for better treatment of prisoners.

She was told in 1968 that Jim had been promoted to captain. Later he was promoted to major. One assumes there is some internal logic to these promotions. He was declared dead by the Marines on February 3, 1978. Presumably there are no more promotions along the way.

He and I, like so many of our generation, were “citizen soldiers.” I don’t think Jim planned to stay in the military any more than I did. But we both grew up in service. The difference was that my growing continued. Jim’s did not.

I didn’t know Jim was MIA, or dead, until many years later. Our correspondence had ceased early in 1966. I was off in the Caribbean and Mediterranean on my own learning experiences, assaulting friendly beaches and determining where life would take me after the Navy. I think my own mom mentioned in passing long ago, “Well, I heard from Jim Egan’s mother that he was missing in action, or dead in Vietnam.”

By then New Jersey, golf courses, Jim and our boyhood friends were squirreled away in a corner of my memory. Then Jim’s letter showed up as I rummaged through the detritus of a move from one home to another. Even later, a note from a woman named Patricia Mielke popped up in my email inbox.

Patty was searching for Jim, and somehow we made the connection. We have corresponded since then, and we have introduced the many “members” of Jim’s family to each other. I told her about my high school crowd, and she filled me in on the Marines who crowded into Jim’s life in 1964 and 1965.

Many of the “family” met Memorial Day 2004.

Jim’s memory came alive near his childhood home of Mountainside, New Jersey, on that day. There his sister, Joanne Buser; his fiancé of 40 years ago, Carole Barskis Weber; and other friends from his high school, college and Marine Corps days gathered to pay homage to their brother and friend. The town of Mountainside dedicated a new street in his honor, Egan Court. Jim was eulogized in perhaps the closest thing to a funeral ceremony he was given since he disappeared on that patrol in January 1966 on the perimeter of Chu Lai.

Larry Clayton is a professor of Latin American history at the University of Alabama.