One hundred mornings a year, more than 8,500 people around the world wake up to an email signed by Thorsten A. Integrity. It contains a link to six difficult trivia questions, as well the name of their head-to-head opponent for the day.

These are the players in LearnedLeague (pronounced learn-ed), a competitive, bracket-style, invitation-only trivia competition with a dedicated player base in all 50 states and 54 countries.

The questions — and the league — come from the mind of its creator and commissioner, Thorsten A. Integrity. But when he’s not devising cleverly worded questions, checking thousands of answers, and maintaining the league’s complex rankings and statistics, Thorsten is better known as Shayne Bushfield ’94.

Bushfield never set out to create the world’s most popular head-to-head trivia league. He started the league — on paper — with a small group of co-workers in the late 1990s. But thanks to his dedication and passion for trivia, a diversion among friends has ballooned into a multithousand member online league with complex statistics and a slate of well-known players such as 74-time Jeopardy! champion Ken Jennings, How I Met Your Mother producer Carter Bays and novelist Anna Quindlen.

The game’s success means that Bushfield, now (likely the world’s only) full-time online trivia commissioner, spends significant time writing questions. “It’s actually taken longer and longer,” he says. “When there’s more players doing it, there’s more pressure on me to not just make it a good question but to make it really good, and exactly right, and really, really tight.” He usually starts with an interesting tidbit from a reference book and builds the question out from there. He fact-checks everything and has his questions professionally copyedited.

- Think you're LearnedLeague material?

- Sample Trivia Questions

His not-so-trivial pursuit started when Bushfield, fresh out of Notre Dame with degrees in history and economics, took a temp position at a law firm in Manhattan. The firm represented tobacco companies, and Bushfield and his co-workers spent their days sifting through subpoenaed medical records, looking for proof the plaintiffs had been warned to quit smoking. “Basically we were like peons working for the smoke companies, against these poor people who had suffered from lung cancer,” he says.

As the temps slogged through records, they invented games to distract themselves, eventually forming a trivia league. They made up goofy rules, awards and terminology (“Learned” was actually the last name of a player). “I would go away to graduate school and come back and work at the law firm in the summers,” says Chris Fettweis ’94, a Notre Dame classmate of Bushfield’s. “And every year it had ratcheted up another level of ridiculousness.” Bushfield’s wife, Amy, was also a temp at the firm and one of the original players.

After the third trivia season in 1998, the players dispersed from the firm. Bushfield left for a consulting job, followed by an MBA at Columbia. LearnedLeague had apparently run its course, lingering as a fond memory. But during a business school internship in 2000, Bushfield became intrigued by the new world of web programming. Seeking a project to practice basic programming, he reached out to his friends about reviving LearnedLeague and set to work building a website.

In the online version of the game, Bushfield added a twist. After each season, current members would be able to refer one new player, as long as they vouched for their friend’s honesty. And so — slowly but surely — LearnedLeague began to grow.

Craig Crossland joined LearnedLeague in 2009. In his first season, there were 294 players, up from the original 20. The Notre Dame professor of business says LearnedLeague has been “one of the highlights of my day for years.”

“The questions are very eclectic, they’re quite interesting, they’re always thoughtful,” Crossland says. They’re also difficult. “I’m not a great trivia player, but I feel like I’m decent,” he says. “But in LearnedLeague, middle of the pack would be generous. It’s very humbling. I’m a professor and we’re not known for our academic humility, so I think it’s good to be reminded that we don’t know everything.”

Kara Spak ’96 is a five-time Jeopardy! champion, but, like Crossland, she doesn’t finish at the top of LearnedLeague.

“It’s not a cakewalk,” says Spak, a hospital spokesperson in Chicago. Unlike on Jeopardy!, “You can’t work your way around the board and kind of minimize the categories you know you’re probably not going to be that good at. You have to answer the questions that are out there.”

But she says she doesn’t play to win. “It’s a nice 10-minute break from my ordinary life. It’s easy to get sucked up in your daily life and never take a break and think about art or science — things you maybe liked learning about in school, but maybe they’re not part of your day-to-day anymore.”

Spak is one of about 100 Notre Dame alumni in LearnedLeague — and, Bushfield estimates, one of up to 200 or 300 former Jeopardy! contestants. She joined in 2013, on the referral of a fellow contestant on the Jeopardy! Tournament of Champions. “It sort of provides camaraderie into this trivia world, this world of like-minded, curious people,” she says.

The site has active message boards where players analyze strategies and discuss how they arrived at correct answers.

“There are pretty strong friendships that exist from people who got acquainted through LearnedLeague,” says Bushfield. “Sometimes they’re still online friends, but other people have met in person, especially if they realize they went to the same college or are geographically close to each other.”

Crossland will send a quick hello in a personal message when he notices his daily opponent is a fellow Australian or Penn State grad. Spak sent a personal message when she looked at her opponent’s name and realized she was playing her older brother’s roommate from Notre Dame, someone she hadn’t seen in years.

Once Fettweis was surprised to hear from an opponent calling it an “honor” to play against someone from the original LearnedLeague group. “Even though I was in it early on, I think I just scratch the surface of what the LearnedLeague community is,” he says. “It’s deep and it’s tight.”

LearnedLeague players have jumped on board with the goofiness of the league, inventing and popularizing terms such as “LLama” (a player in LearnedLeague) and “pavano” (someone who forfeits all 25 games in a season by not submitting answers, named after a pitcher who was injured for most of his four-year contract with the Yankees). Along with cheating, forfeiting is a huge no-no and can result in suspension the following season.

LearnedLeague’s structure is complex. The 8,500 players are assigned to one of about 40 leagues. Within each league, players are further divided into skill-based divisions called “rundles.” Over the course of a 25-day season, each rundle functions as its own round-robin tournament. At the end of the season, top performers are promoted to a higher rundle, and the winners of each league’s highest rundle can qualify for the championship, held live in Las Vegas. The overall season champion earns bragging rights and a custom scarf.

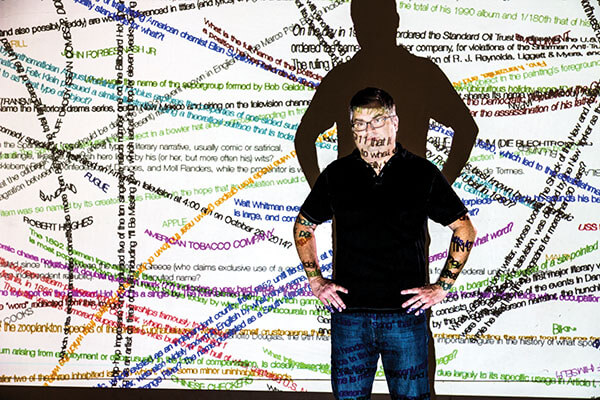

The creator and head honcho of 'the coolest, weirdest, Internet community you'll never be able to join,' according to The Washington Post.

The creator and head honcho of 'the coolest, weirdest, Internet community you'll never be able to join,' according to The Washington Post.

There is a catch to LearnedLeague scoring: Winning a head-to-head match isn’t just about answering more questions correctly. Instead, when submitting answers, players also “play defense” by assigning point values to their opponent’s answers (for the six questions, a player must assign one 3, two 2s, two 1s, and one 0). If the opponent gets the correct answer, they win the points. A savvy player will minimize an opponent’s scoring by assigning 0 points to a question in the opponent’s strongest category. To facilitate the playing of defense, players can look up enormous amounts of performance data on themselves and everyone else in the league.

“I think that’s been the appeal of it for a lot of people, all the different ways you can track data about players and about the league,” says Bushfield. “I think there’s a lot of appeal to a player — outside the competitive head-to-head aspect and how you finish in the table — to seeing what you know that other people don't know and, conversely, what you don't know that everyone else seems to know.”

When Bushfield finished business school and went back to work in 2001, LearnedLeague had 38 players. By 2012, LearnedLeague hit 1,000 players and took significant time to wrangle. Bushfield announced that he would start charging a small yearly fee (currently $30, with perks like extra referrals available at higher levels). “I was worried that some people would bail,” he says. “And some did, but far, far fewer than I expected. It's kind of an interesting business case. Once I started charging for it, then that basically assigned a value to it, which made it more valuable in a way.”

By 2014, “it got to the point where it was getting too big to do as a hobby. So I had to decide whether I wanted to keep growing it or stop, basically. But to keep growing, it would mean I would have to leave my job at Microsoft.” At this point, Bushfield and his wife had 7- and 10-year-old sons. But knowing that growth was steady and people were willing to pay, he decided to take the plunge.

“It was incredibly risky, but it wasn't just a wild jump off a cliff,” the Seattle resident says. He planned out the coming months and determined, “by this date it needs to be at this point, or I need to start thinking about updating my resume.” Membership numbers met the various milestones he set, however — at the ends of 2014, 2015 and 2016, membership passed 2,800, then 4,800, then 7,200. Bushfield jokes that if this growth rate continues, everyone on earth will be in LearnedLeague by 2038.

“It’s so much fun to have a friend who did something that took that kind of guts,” says Fettweis. “Who said, ‘I’ll leave the corporate world with its nice packages and incentives and health insurance and all this stuff. I’m going to leave that and go full-time into trivia.’ That takes some guts. Or total insanity, one or the other.”

Growth is steady, but invites to the league are scarce. Wannabe players angle for referrals on social media and Jeopardy! fan message boards, prompting The Washington Post in 2014 to call LearnedLeague “the coolest, weirdest Internet community you’ll never be able to join.”

But keeping people out was never the point. “It’s not meant to be exclusionary, or exclusive, or private, or just for certain kids or anything like that,” says Bushfield. The referral system was devised to limit cheating — the answers are obviously a Google search away — by making sure new players had someone to vouch for them. For the same reason, players must sign up under their real names and click a box promising they did not cheat before submitting answers.

Over LearnedLeague’s 73 seasons (four each year), Bushfield has written more than 10,000 questions. He aims for the league-wide correct-answer rate to sit a little below 50 percent. “In my opinion, that’s the sweet spot where really good players still are challenged occasionally and the very bottom players still get some right,” he says. Last season, he hit his goal with a league-wide rate of 48.07 percent.

Thanks to automation, grading takes much less time. Correct answers, as well as variations and misspellings (such as “Lincohn” for “Lincoln”) are all automatically marked correct. Answers containing letter combinations that appear in the correct answer (“such as “lin”) are highlighted as possibly correct, and everything else is marked wrong. It takes Bushfield about 20 minutes to skim the possibly-correct lists and complete the day’s grading.

It all makes for a seamless experience for his 8,500 LearnedLeaguers.

“I don’t know how he does it,” says Spak. “I’ve definitely botched a few of the spellings but had the right answer and it counted.”

“He runs it really well. I’m amazed by how on top of things he is,” says Crossland. “I’d be deeply sad if Shayne were to close this down. I think there’s a lot of people like me that really enjoy this.”

Sometimes, Bushfield ponders this strange career he invented for himself. He says he recently had a conversation with Ken Jennings — another person who has come to be defined by trivia — about giving career advice to their children. “It’s like, don’t look at us as an example,” jokes Bushfield. “This is not normal! You can't plan to do this sort of thing. You can’t plan to run a trivia league for your job.”

But in a way, it makes perfect sense. This is, after all, the guy who created a trivia league from scratch to entertain co-workers. Long before that, Bushfield says, he would lie on the floor of his childhood bedroom with a deck of Trivial Pursuit cards and a notepad, carefully tracking his knowledge in each category. “And if you think about it, that’s kind of the two sides to the appeal of LearnedLeague,” he says. “The trivia and the statistics.”

He had his “first glorious moment of trivia” in high school, when his quiz bowl team won the championship on Brain Game, a long-running quiz show on Indianapolis’ NBC affiliate. Years later, while living in New York post-college, he competed with several other Notre Dame alumni on Remember This?, a short-lived MSNBC trivia show hosted by Al Roker.

“If you had told me, ‘One of your friends is going to be a commissioner of a trivia league,’ it would certainly have been Shayne,” says Fettweis. “One of the weird things it seemed like he knew — like, the second week of college — is where everybody was from. I mean, everybody. He may still remember where most people from the Notre Dame class of ’94 are all from.”

Despite his own knack for trivia, Bushfield is blown away by the talent in his game. If he were to play, he says, “I definitely wouldn’t be one of the very top players, that’s for sure. Those people are in a different league. It’s really a skill that’s kind of something to marvel at.”

He’s happier on the commissioner side of things anyway.

“I guess the lesson is, you could make all kinds of plans in your life, and you just don’t know how things are going to work out,” he says. “I just had a thing on the side that I really enjoyed doing, and so I worked hard at it. And it just grew and grew, and eventually it became something I could do for my job. It was just an opportunity that I couldn’t pass up.”

Katie Rose Quandt is a Brooklyn-based freelance reporter who has written for Slate, Mother Jones, Brooklyn Magazine and other publications. Her email is katierosequandt@gmail.com.