Matt Cashore ’94

Matt Cashore ’94

It was late September, 1963. Father Theodore Hesburgh took a phone call from Dr. Roland W. Chamblee, a local African-American physician and Catholic who counted the older priests and brothers of Holy Cross among his patients. But this was not about a routine check-up.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had accepted an invitation to speak in South Bend on October 18, Chamblee informed Notre Dame’s president. Would it be possible for him to secure a venue on campus?

Hesburgh was already well-known for his support of civil rights as a member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission. He told Chamblee this was very short notice for an event of this magnitude. Still, Hesburgh contacted the doctor the next day to say that King was welcome at Notre Dame and could speak at the brand-new Stepan Center.

The carefully researched story was told by Monica Maria Tetzlaff, an associate professor of history at Indiana University of South Bend at a September 25 event marking the 50th anniversary of King’s visit. At least two people in the 50-person audience at the new Notre Dame Center for Arts and Culture on South Bend’s West Washington Street were present on the night of King’s speech and had provided Tetzlaff with documents and interviews during her research.

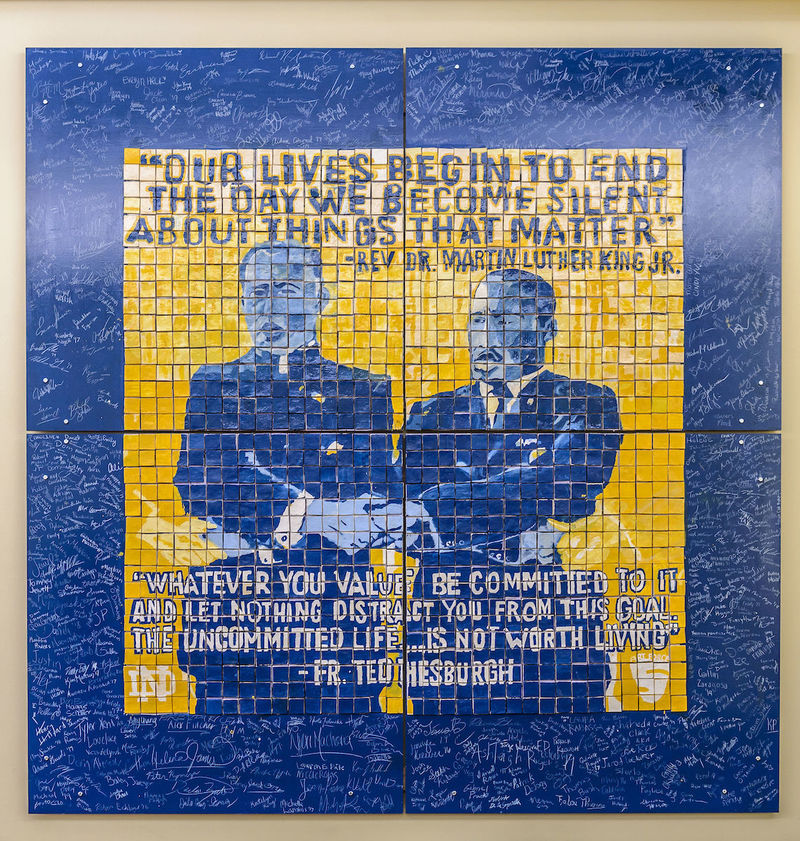

While the photograph of Hesburgh and King clasping hands and singing at a 1964 rally in Chicago has become iconic — the image was installed in the National Portrait Gallery in 2007 and hangs also in the God Quad entrance to the LaFortune Student Center — few at Notre Dame today know that the civil rights champion and revered Southern Baptist minister from Montgomery, Alabama, made an appearance on campus before that picture was taken.

There was only one problem with Stepan as a venue, Tetzlaff said. It had no chairs. But a local event rental company came through, donating 3,000 seats and the labor to set them up and take them down. Meanwhile, South Bend’s African American community and civil rights supporters on and off campus mobilized to prepare for the event.

It was a signal year in the American civil rights movement. The Birmingham, Alabama, police had turned their hoses on black demonstrators in May; the televised and published images generated widespread support for their cause. King had delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August. And in mid-September, a bomb went off in Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, killing four girls.

In South Bend, one month later, King focused his remarks on the civil rights bill pending in Congress and set the American scene in the context of the international independence movement that was bringing the centuries-long era of imperialism and colonialism to an end. The evening raised money for King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as well. Donors, even children giving no more than a dollar, received cards that read, “This certifies that _____ has invested $_____ in the Freedom Struggle in the South.”

The big night at Stepan began at 8:15. Famed gospel singer Mahalia Jackson’s organist, Louise Overall Weaver Smothers, performed. Notre Dame’s executive vice president, Father Ned Joyce, CSC, offered a welcome and King’s right-hand man at the SCLC, Ralph Abernathy, warmed up the crowd as he usually did before King’s public appearances.

King then delivered his consistent message decrying discrimination in jobs, housing and education, saying that even though the old order of belief in racial superiority and inferiority was passing away, the new order of equality carried subtler expressions of racism, such as allegations of latent “criminality” among American blacks, that could be equally dangerous.

“It is a torturous logic to use the results of segregation and discrimination as an argument for the continuation of it, rather than looking at the causes,” King told the crowd. He advocated for political action in support of keeping the proposed civil rights legislation strong, even as President John F. Kennedy was pushing for a softer bill that could still pass to his political advantage.

Tetzlaff said King’s trip began with an invitation from Alphia Ganaway, a prominent member of South Bend’s African American community who was active in the local branch of the NAACP, the Republican Party and Pilgrim Baptist Church. But in writing King, she acted on her own and not as a representative of any group. Later asked why she’d done it, Ganaway said, “Well, I just thought we needed him here.”

Tetzlaff played segments of footage from King’s speech that was obtained from the University of Notre Dame Archives, a shorter clip of which was part of an exhibit at the Snite Museum of Art commemorating King’s campus visit.

Her talk, “King in South Bend,” was part of a year-long series of programs and events entitled “The Africana World: A Historical and Cultural Mosaic” that is being coordinated with South Bend and campus partners through the Notre Dame Center for Arts and Culture and the Office of Community Relations.

Were you on campus in October 1963? Share your memory of Dr. King’s visit with associate editor John Nagy at jnagy1@nd.edu.