Isaac Newton, no slouch as a scientist, theorized in the late 1600s that the hand of God stabilized planetary orbits. A century later, Pierre-Simon LaPlace applied more advanced mathematics to disprove his predecessor’s higher-power hypothesis.

During a June 16 talk at Notre Dame’s Jordan Hall of Science, Vatican astronomer and Jesuit brother Guy Consolmagno related a (probably apocryphal) story about LaPlace presenting his discovery to Napoleon, who asked after the absent God.

“I have no need for that hypothesis,” LaPlace told the French ruler, an answer that, if the exchange ever happened, would have been exactly right in Consolmagno’s estimation.

Napoleon, like Newton before him, was looking for the God of the gaps, an unreliable narrator lurking between the lines of the natural world. For Consolmagno, that’s the wrong way to conduct research or practice religion. “Because after the hole gets filled, the thing you were basing your faith on suddenly evaporates.”

And anyway, it would be a cheapened deity that could be reduced to spackling cracks in human knowledge. “A God who is just one force alongside all the other forces in nature is not the supernatural God that I have encountered in the Bible, that I have encountered in prayer,” Consolmagno said. “It’s a nature God. It might as well be Zeus throwing lightning bolts. It’s a pagan God.”

His God stands apart, outside of time and space, delighting in the birth of new stars without being the spark that sets them aflame. At least that’s how Consolmagno perceived God when he felt assured of his own free will.

Responding to a question about whether he believed God guided the creation of new stars, he explained how that certainty came to elude him. God would love him, he felt sure, whatever path he chose in life. But not until he was almost 40 did he choose the Jesuit religious direction, realizing when he arrived that God had led him there. As if an unseen hand had steered his orbit, however far away he may have drifted from the sun.

“But, but, but,” Consolmagno spluttered, recalling his dawning sense of destiny, “I thought I was supposed to be able to do whatever I want.”

He still doesn’t doubt that God’s love would have followed him anywhere, but he can’t deny that he’s wired much more to the specifications of a Jesuit brother than, say, an NBA player. Which prompted him to ask, “How much is freedom, how much is destiny? That’s a mystery and I don’t have an answer to that.”

Whether or not he has all the answers, Consolmagno fields many questions from people wrestling with mysteries of faith amid the immensity of the universe. He collected some responses in the book, Would You Baptize an Extraterrestrial? … and Other Questions from the Astronomers’ In-box at the Vatican Observatory. (Short answer about christening ET? Only if she asks.)

An astronomer for four decades and a practicing Catholic all his life, Consolmagno is now president of the Vatican Observatory Foundation. Wearing a Roman collar and an MIT ring, he said, marks him as both “a fanatic and a nerd.”

Last year he received the Carl Sagan Medal from the American Astronomical Society for outstanding communication of planetary science to the general public. A gray-bearded, amiable presence in front of about 150 people last week at Notre Dame, he hopped easily across cobblestones of conversation: meteorite hunting in Antarctica, multiverses, the warming planet’s rising seas, insights from science fiction, and the confusion of communication between science and religion.

That confusion seems to underlie many of the inquiries Consolmagno gets. Language blurs more than it clarifies, he said, because listeners attach their own meaning to words. Like “design.” As in, “Can you see God’s design in the universe?”

Consolmagno said no, in the sense that God is not awaiting detection by better technology, disguised only by a lack of available data. He’ll take LaPlace’s explanation of the orbits over Newton’s.

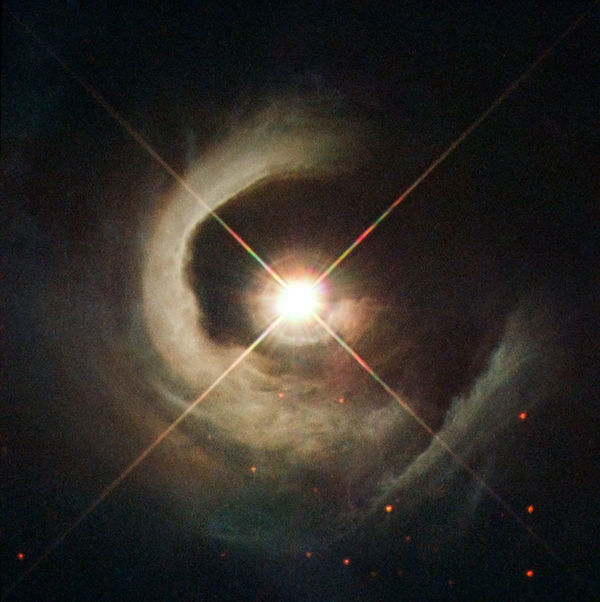

Yet every image he’s ever seen from the Hubble Space Telescope has been beautiful beyond explanation. That, Consolmagno reflected, offers a glimpse of God.

“Because I come to the universe with this faith, I can see God’s spirit, God’s artisanship, God’s phenomenal love of elegance and beauty everywhere I look in nature.” In that spirit, the Vatican astronomer said, scientific research is ennobled as an act of worship.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.