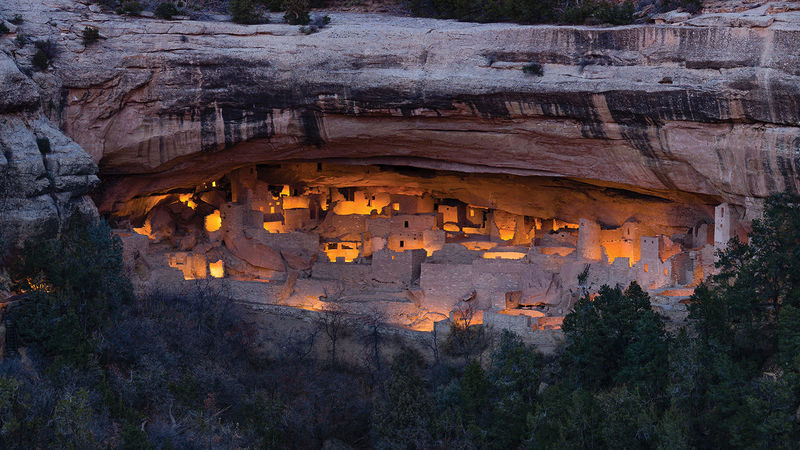

We’re sitting in silence in the Long House cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park, watching the sun swallow the shadows across the far canyon wall.

I strain to hear the whispers of the ancestral Pueblo people who built the complex villages tucked into massive sandstone alcoves in southwestern Colorado, then left them sometime in the late 13th century. I can feel their presence viscerally, emanating from the soot they scorched into the rock and the small imprints of maize in the mortar.

Photo by David Schneider

Photo by David Schneider

Villages like Long House were surely loud and bustling places, among the most densely populated settlements found in any Native American culture. They were connected to each other, too — a dozen dwellings of various sizes can be seen from the park’s Sun Point Overlook. The Mesa Verde civilization flourished in these mountains and valleys for nearly seven centuries, but by the year 1290, the ancestral Pueblo clans had vanished from this region for good, having migrated south and west into modern-day Arizona and New Mexico.

The park, which covers about 81 square miles, is dotted with nearly 5,000 archaeological sites. Here the ancestral Pueblo people left scattered clues about who they were — from crumbled walls and the occasional petroglyph to broken pottery and the building footprint of each community. Archaeologists like Donna Glowacki, sitting with me in the silence, are trying to read these signs.

Glowacki, a Notre Dame anthropologist and expert in Mesa Verde culture, studies societal collapse. An estimated 25,000 to 40,000 people left this homeland between 1250 and 1285, one of history’s great migrations. Why they left is one of North America’s great mysteries, and it has animated Glowacki’s work for 25 years.

“I’m really interested in how societies change, and how we deal with really tough situations, and what happens when it just doesn’t work,” she says.

Science can prove a drought occurred here in the late 1200s, but a previous generation had survived severe drought a century earlier. After the first drought, people moved from their mesa-top farms to walled villages on cliff edges, then to more defensible positions under the cliffs as a last resort, suggesting that scattered communities had grouped together for safety as resources became scarce. Other sites corroborate the theory that this crowding led to violence between different Pueblo clans. At Castle Rock, an outcropping of stone just outside the park, early explorers found unburied bones that indicate the village ended in an attack, rather than a move.

So what was different during the second drought that caused people to leave these lands forever? Glowacki says the question bears no single answer, pointing instead to what the archaeological evidence suggests about social and religious practices in different communities.

“Different Pueblo groups dealt with that question in super-different ways, but came to the same conclusion: that this is not working,” she says. “They decided, ‘We need to think about things differently. The way we’re going to do that is to move to some other place, where we can in some ways start over.’”

Glowacki thinks in terms of centuries and civilizations, making it easier to find answers by looking at the big picture. In the 21st century, she says, we face challenges the Pueblo people of 800 years ago would recognize: climate change and economic turmoil resulting in mass migration, with some political systems failing and others surviving.

In his July 17 column, Thomas Friedman of The New York Times wrote: “So much of the immigration that has swamped Europe of late has come from migrants from Syria and sub-Saharan Africa. Both migrations are the product of political turmoil fed by climate change, the collapse of small-scale agriculture and rapid population growth in the Middle East and Africa. (Ditto Central America.)”

Photo by David Schneider

Photo by David Schneider

Glowacki believes studying the 13th century can shed light on our current challenges.

“It all matters because it sets the tone for what’s happening in the present,” she says. “We have to understand all the different ways we have changed over the years, how we’ve adjusted to economic turmoil or climate change, or pick whatever issue you want. The way we can understand the ramifications of what we’re doing in today’s world is by understanding what people did in their contexts, and what happened to them.”

Immigration and its consequences were driving forces in recent presidential elections and in the Brexit vote. Some countries, like Russia and Hungary, have turned to a strong authority figure to lead them through turmoil, whether it’s real or imagined by those seeking power. Anti-immigration, authoritarian parties have emerged in countries like France and Holland, but moderate voters have rejected them.

These are all political responses to the fallout from forces similar to those that roiled 13th-century Mesa Verde. In the years after the fall of Soviet Union, the spread of democracy seemed inevitable. Yet the last few years have punctured that certainty. Studying the forces that cause a collapse and how a society recovered afterward seems more relevant today than ever.

Moving on up

Glowacki, 49, landed in Mesa Verde by accident. Before starting graduate school at the University of Missouri, she needed a summer job and found one as an interpretive ranger in the park in 1992. It didn’t take long for her to fall in love with the landscape and the mysteries of ancestral Pueblo culture.

Photo courtesy of Kay E. Barnett

Photo courtesy of Kay E. Barnett

With her master’s degree in hand, she began working at the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez, Colorado, about 10 miles from Mesa Verde. There she helped excavate and study Yellow Jacket Pueblo, among the largest village sites in the region. In 2005, she took a position as a National Park Service archaeologist and worked on a project at Spruce Tree House, one of the three largest cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde. Park archaeologist Kay Barnett, one of Glowacki’s collaborators in that project, guided us on our visits to Cliff Palace and Long House in July, allowing us to enjoy these places in eerie silence.

Glowacki came to Notre Dame in 2007 after completing her doctoral degree at Arizona State, but she continues to work closely with partners at Mesa Verde and Crow Canyon. While the cliff dwellings get all the glory because of the awe that the quality of their preservation and the beauty of their settings inspire, she insists on taking visitors on a longer tour of ancestral Pueblo history that begins on the mesa tops and ends beneath the cliffs.

Evidence of nomadic Paleo-Indians in the American Southwest stretches back more than 10,000 years. A basket-weaving culture that combined foraging and hunting with early maize cultivation emerged in the Mesa Verde region by about 1000 B.C.

The first year-round habitations, or pueblos, in the wide valleys of the region can be dated to A.D. 650, around the time that a growing reliance on agriculture led to the establishment of more permanent settlements. These were pit structures, dug into the ground in circular shapes with wood frames covered by mud walls.

Little of these pit structures remains, but Glowacki points out architectural elements like the vent shaft, fire pit and heat-reflecting stone that would survive the transition into stone-and-mortar construction. Seeing the evolution from pit houses to two-story stone towers through Glowacki’s eyes offers a fascinating look at centuries of human progress in one place, as structures were sometimes even built one on top of the other.

The most prominent features of the later dwellings are the circular, subterranean kivas. The modern Pueblo people still use them as formal, ceremonial spaces. A cross between a church, a living room and a school, a kiva in the past may have had many functions: as a place for rituals, for family or community gatherings, for passing on Pueblo traditions. In some villages, kivas were large enough that they seem to have been designed more as public gathering spaces than as household shrines.

Classic Mesa Verde homes were built with a row of four to six rooms running east and west. The room block abutted a kiva of proportional size nearly always situated to the south. Kivas had flat roofs with a hole in the middle through which people entered by ladder, though many kivas had access tunnels from the rooms as well. The north-south orientation of the home and kiva was important; the fire pit and vent shaft inside the kiva also followed this north-south axis. South of the kiva lay the midden, where people threw their trash — now an archaeologists’ treasure trove of broken pottery, bones and scraps.

Many of these sites out in the desert remain undocumented. Today, such a site looks like a mound of stones, a circular depression and scattered pieces of pottery. With minimal training, I learn to spot them as we tramp through the foothills outside the park. Naturally, Glowacki’s vision is far sharper. She can tell whether a site had a two-story tower by the height and width of the mound, and roughly date a site by its layout alone.

Evolving theories

In the 19th century, archaeologists believed that ancestors of the Ute, Apache and Navajo tribes may have pushed out their more peaceful farming neighbors, the Pueblo clans. But later studies in tree-ring data discovered the drought that hit in the 1270s, changing the prevailing theories.

Glowacki is part of an interdisciplinary effort called the Village Ecodynamics Project (VEP), founded in 2001. This group of government and university scientists uses archaeological data, climate reconstructions and computer modeling to simulate how the ancestral Pueblo communities might have responded to changes in their environment. The level of detail produced is unprecedented in studies of prehistory. Discrepancies between VEP models and the evidence of ongoing archaeological study have raised important new questions.

The VEP has drawn a more complex picture of a society that weathered many challenges before disappearing. According to its findings, the region’s first drought, around 1130-80, pushed people out of the valleys and concentrated them on the mesas, where greater precipitation, water-trapping loess soil and a longer growing season made farming corn possible, even during cold, dry years. This local migration led to overcrowding and cultural conflict among different Pueblo groups. Evidence of the decline of timber for home building and of deer bones in the middens indicates changes that this growing human population caused, such as deforestation and the near-disappearance of the deer. When the 13th-century drought again strained agricultural capacity, the ancestral Pueblo political structure could not contain the ensuing violence.

“Although the buildup of change and tension was long in the making, the transformation happened quickly in the latter half of the 1200s,” Glowacki writes. “The collapse was precipitous, turbulent and beset with endemic warfare.”

Photo by David Schneider

Photo by David Schneider

Some clans moved out of the region, while others made for the cliffs, combining to build villages like Long House that were occupied only in the century before the society collapsed. It’s difficult to trace the migration of different Pueblo clans to what’s now Arizona and New Mexico because they did not travel in a single group, or build permanent settlements along the way, but village remains in those states show a growing population after 1300. Utes and other tribes appear to have moved into the Mesa Verde region after it had emptied.

“There’s evidence that leaving was a trickle at first, then a flood at the end,” Glowacki says.

She writes in Living and Leaving: A Social History of Regional Depopulation in Thirteenth-Century Mesa Verde that it is “curious” that the clans did not return home after the drought and violence subsided. “The collective memory of what happened in Mesa Verde may have kept ancestral Pueblo people from returning to live in the Northern San Juan [mountains] again: what happened there was just too terrible, and they did not want history to repeat itself.”

She has focused much of her recent research on what the architectural remains show about ancient Pueblo social organization. In Living and Leaving, she concludes that drought, overcrowding and resource stress — the “standard trio” of societal collapse — were present, but that social changes and problems were more important factors.

“They did not leave because of the standard trio; they had to leave because the way they were organized did not work for their times,” she explains.

The way they were organized owes a great deal to the influence of their ancestral Pueblo neighbors in Chaco Canyon and other settlements located in present-day northwestern New Mexico. There people built enormous “great houses” with hundreds of rooms. Anthropologists believe these structures indicate significant stratifications of power, wealth and access to the kivas within each community. Translated north to Mesa Verde, this hierarchical structure was robust enough to survive the 12th-century drought, but it appears to have broken down over time. Fleeing the second drought, the ancestral Pueblo people did not bring it with them to their new homes to the south, where they built new villages with shared kivas and open ceremonial and gathering spaces.

“Ultimately, at the end of the 1200s, as people migrated somewhere else, those elements that emphasize differences get dropped out,” Glowacki explains. “You see them emphasizing a more communal way of relating to each other. That’s a huge change.”

Tracing time

Before we toured Mesa Verde, Glowacki took me to important sites outside the park. Sand Canyon Pueblo was a large mesa-top village occupied in the 1200s. It had an enclosing wall, lookout towers and more than 400 rooms and 90 kivas, so it’s about twice the size of its more famous neighbors like Cliff Palace and Long House. Hundreds of people lived here. The layout of the homes is also different from the classic style that ancestral Pueblo builders had followed for hundreds of years.

“North-south cosmology was a really important way they oriented to build,” she says, connecting the structures’ orientation to the rituals performed in the kivas. “Then, around the 1220s, you don’t see that any more. You see the houses packed more tightly here, and they are oriented around the central drainage and the topography of the canyon cliff.”

The residential area of Sand Canyon Pueblo stood on one side of the drainage, while a communal area with a great kiva and other public buildings were on the other. Glowacki says the site reveals a modification of Chaco-inspired hierarchy and ritual even before the final migration.

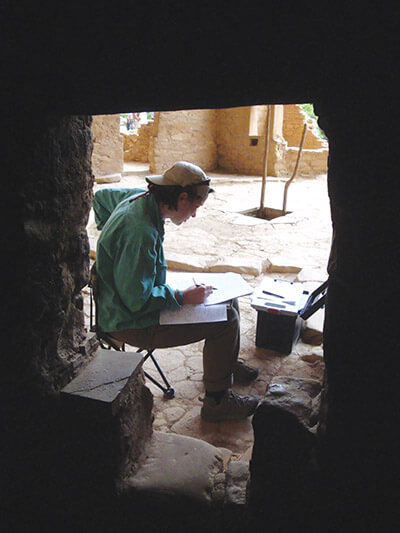

In Mesa Verde, much of Glowacki’s recent work has been at Spruce Tree House, temporarily closed while park officials figure out how to keep large stones from falling off the cliff above. Along with the park archaeologists, her work has included exhaustive documentation of the dwelling’s existing walls as a baseline for park management and stabilization plans. The ancestral Pueblo people were constantly modifying and expanding their homes, and Glowacki wants to see how different wall placements and building methods might indicate the village’s growth over time.

“It really means you stare at a wall for hours,” she says. “You need to pay attention to the placement of each rock. Archaeological excavation is a destructive science. Once you remove anything, you’ve altered perceptions of it. If you remove dirt, you’re the only person who will have seen it the way it was, and what artifacts were in it. You have to take good notes.”

Now she is finishing her analysis of that data. She’s also working with several graduate students to fill in the collective knowledge of Pueblo sites and movements in the centuries before they built the cliff dwellings.

Two Notre Dame graduate students in anthropology, Kelsey Reese and Sean Field, drive with Glowacki to some foothills just north of the park. The land is owned by a patchwork of private landholders and the Bureau of Land Management. Exiting the car, they both put on leather hats that resemble what Indiana Jones wore.

They smile when I ask if the hats are the best part of being an archaeologist. Their labor is a dazzling combination of old-fashioned legwork and cutting-edge technology.

Field science

It’s pretty thrilling to walk up on an unexplored site. “Unexplored” doesn’t mean no one has seen it — there have been ranchers, cattle and hunters here for years. In most cases, locals know they exist. But Reese and Field are working to make the archaeological maps of the foothills of the North Escarpment, a range of mesa cliffs marking the park’s northern edge, more complete.

“The hard thing about archaeology is that we’ll never know for sure if any of our conclusions are right,” Reese says.

But the signs are not impossible to read. I’m shocked by how many pottery sherds (as opposed to “shards,” which suggests glass) are lying on the ground rather than buried beneath the dirt. The students conduct a pottery tally to date each site. They measure a three-meter circle in one promising midden. We collect all the sherds on the surface. Field and Reese separate them by characteristics that correspond to different eras.

Photo by David Schneider

Photo by David Schneider

The pieces may be kitchenware, corrugated to dissipate heat, or they may be formal black-and-white designs used in rituals. A sherd’s thickness, rim, complexity of pattern and type of paint (mineral or organic) reveal its era. The students consult each other, Glowacki or a field guide to date a tricky piece. They spot gizzard stones that show people here were eating domesticated turkeys, which means the site was occupied after spikes in the human population had decimated the deer.

I stare at some intricate patterns on a few of the hundreds of sherds. The modern Westerner in me wants to take one home, maybe show the kids — to own this piece of American history. Of course it’s illegal to remove any artifacts from a site. More seriously, I think about the bad vibes such a violation might bring. I put the sherds down.

A Chicago native, Reese first visited Mesa Verde when she was 11 and decided then to become an archaeologist. Today she walks around looking for “check dams,” simple rock formations that ancestral Pueblo growers used to create silt fields — richer soils for farming purposes.

“Check dams are what I nerd out about,” she says. “It’s a tiny investment for a huge payoff. Just by putting a few rock dams in a runoff and waiting a few years, you create farmable land. All together, they created thousands of acres.”

Field, who grew up on a ranch in Colorado, uses a GPS device to precisely outline the walls, the size of each kiva, the spread of the midden. He tramps through sage bushes to get readings accurate to within centimeters, then takes a drone out of a backpack and gets it ready to fly.

Reese has programmed the drone to take hundreds of pictures from three different heights over a designated square in the sky. They’ll stitch the pictures together to create a topographical map of the foothills complete with flora and prehistoric sites.

The goal is to track the movements and dynamics of the settlements along the North Escarpment. Years of this kind of grunt work will give them the experience and knowledge base to do the kind of big-picture analysis Glowacki does.

Photo by David Schneider

Photo by David Schneider

We walk the hills for a few more hours on my last day in Colorado. Reese warns me not to get my hopes up for something new: “It’s not what you find, it’s what you find out,” she says.

Then we struggle up a ravine and find evidence of a stone tower the students have never seen before. Even better is a boulder with holes for rainwater. Imagine bashing one rock into another to bore a hole large enough to contain a few cups of water. That level of effort makes me ponder how difficult existence was in such a dry climate.

I think back on the silence of Long House, that moment right after Glowacki explained the shift from tribal elites and hierarchy to a more communal way of living, and I decide I like her theory because it’s so optimistic: The ancestral Pueblo people didn’t need authorities to tell them how to build or worship or when to leave. They determined as a group that they needed a change.

“There’s a lot of resilience and cohesion, to say, ‘This is what makes us Pueblo, but we’re going to move in this other direction,’” Glowacki says. “How does a society do that? What does that tell us about today and the kind of problems we’re facing?” The preservation of history, she believes, helps us to be the best version of ourselves, teaching us how to react to big, threatening changes and move forward.

Brendan O’Shaughnessy works in communications for Notre Dame. A former teacher and Indianapolis Star journalist, he is the co-author of three Notre Dame books for children.