Almost 70 years had passed since Captain Charles D. Stapleton was killed in action.

The white cross offers very few clues of the life so honored there. It is one of 9,387 white crosses that stand in disturbingly long rows at the Normandy American Cemetery in France, the final home for Americans killed in World War II.

Etched into the stone cross is name and rank and home state: New York. His regiment: the 117th Infantry. His division: the 30th Infantry. His date of death: July 12, 1944.

That’s it. But it’s not quite where this story begins.

It could be said to begin with Chris Hasbrook ’89 of Wilmette, Illinois, who in 2012 planned a visit to the cemetery. He thought that finding a single white cross marking the resting place of one fallen soldier would make his visit more personal.

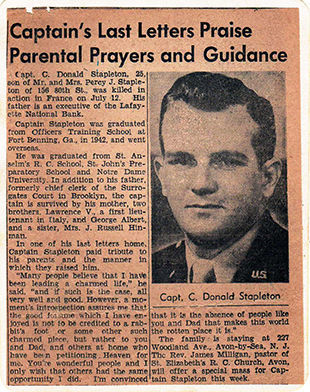

He contacted the Notre Dame Alumni Association and was given the name Charles D. Stapleton. There’s a yearbook photo. White shirt, tie and suit jacket. Dark hair parted on one side and combed back in the style of the ’40s. He was from Brooklyn.

Hasbrook explored his military status. KIA, killed in action. For which Captain Stapleton received the Distinguished Service Cross, given posthumously for “extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy.” The citation says his “outstanding leadership, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty at the cost of his life exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself.”

That award for “valor,” a census record and the yearbook photo were all Chris Hasbrook had to go on.

Library visits and internet searches turned up nothing more. Stapleton was a common name. There were no children, just little pieces of a short life that ended on a battlefield in Europe.

Then a possible breakthrough. Hasbrook came across an obituary for George A. Stapleton. Captain Stapleton had a brother named George. Could this George Stapleton be his brother? A son, Don, was listed among George’s survivors. Donald was Captain Stapleton’s middle name. Could this Don be his nephew?

Hasbrook left a phone message asking for help, and he eventually heard back from Linda Chadwick — Captain Charles Stapleton’s niece. She said her uncle went by Don.

Hasbrook soon learned that Charles Donald Stapleton had been born October 7, 1919, in Brooklyn, to Helen and Percy Stapleton. He attended St. Anselm Catholic Grade School and St. John’s Preparatory School before entering Notre Dame. He graduated in 1941. His parents, Hasbrook reports, “were so proud of him that they rented a passenger rail car from New York to attend his graduation in style and comfort.” His Army enlistment papers note his profession as “actor.” He finished Officer Training School at Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1942.

“In the face of direct machine gun fire from enemy tanks and intense small arms fire only 70 yards to his front, Captain Stapleton, without regard for his own personal safety, went forward on four different occasions to rescue a wounded comrade.”

In the spring of 1944, Don Stapleton was in England with troops preparing to invade France. He became very close to an English girl from Berkhamsted named Valerie Smith. There is a photo of the couple smiling into the sunshine, Don in dress uniform, Valerie in a white blouse and grey pleated skirt, their arms interlocked. There is also a photo of Stapleton’s battalion landing on Omaha Beach in Normandy on June 10, 1944 — four days after the initial assault on the beachhead.

The numbers are staggering, and bear repeating today. According to the D-Day Museum, more than 425,000 Allied and German troops were killed, wounded or went missing during the Battle of Normandy. This includes 37,000 Allied ground troops killed and another 16,714 deaths among Allied air forces.

Don Stapleton survived one month of fighting until his death just south of Hauts-Vents, France.

A letter to Don Stapleton’s father from the Adjutant General’s Office explains what happened: “As Captain Stapleton’s unit was advancing rapidly to its objective, it was pinned down by a surprise enemy counterattack consisting mostly of heavy armor,” and “the battalion suffered many casualties.” The letter says, “In the face of direct machine gun fire from enemy tanks and intense small arms fire only 70 yards to his front, Captain Stapleton, without regard for his own personal safety, went forward on four different occasions to rescue a wounded comrade.”

Because of Stapleton’s “courageous leadership and exemplary actions,” the letter states, the Nazi “counterattack was repulsed.” That was July 9, 1944.

On July 12, Stapleton’s unit was again “pinned down by heavy artillery and machine gun fire from well emplaced German tanks.” However, Captain Stapleton “resolved to push the attack despite the heavy fire,” and “took a handful of men” and “forged ahead boldly and aggressively until a full-scale assault was underway.”

It adds: “Mortally wounded in the assault, Captain Stapleton continued to urge his men forward until the objective was captured.”

Through Stapleton’s remaining family Hasbrook found his obituary from a Brooklyn newspaper. In it are a few lines from one of Stapleton’s final letters home to his mother. “Many people believe that I have been leading a charmed life,” it reads, “and if that is the case, all very well and good. However, a moment’s introspection assures me that the good fortune which I have enjoyed is not to be credited to a rabbit’s foot or some other such charmed piece, but rather to you and Dad, and others at home who have been petitioning Heaven for me.

“I’m convinced,” he writes, “that it is the absence of people like you and Dad that makes this world the rotten place it is.”

Then there is the letter from Don’s friend and fellow Army officer Lt. Harold Powe to his English girlfriend, Valerie Smith. In it Powe writes, “It was a severe blow to me and I refused to believe it until I saw him myself. I didn’t have courage enough to look at him under the cover ’cause I wanted to remember him always as Don with a smile and a good-natured remark for you.” The unit’s chaplain, Powe noted, “personally saw to the burial, and being a very close friend was deeply grieved by it.”

Hasbrook’s taking a personal interest in Captain Charles Donald Stapleton and his persistence helped bring his fellow Domer into sharper focus, enabling the young war victim to be more of a real person, in a sense bringing him to life decades after his death.

But the story doesn’t quite end there. Hasbrook, who visited the cemetery for the first time in 2012, didn’t know about the Les Fleurs de la Memoire program. It’s a grave adoption program through which Europeans, mostly French and English, adopt a serviceman at the Normandy American Cemetery and pledge to visit the adopted grave each year and place flowers there to honor the sacrifice of the soldiers who helped liberate Europe from the Nazi occupation.

Don Stapleton’s grave had been visited annually by the Boutringain family for decades. And in June 2014 — 70 years after Captain Stapleton landed at Omaha Beach — Chris Hasbrook met Mr. and Mrs. Roger Boutringain at the cemetery and went on to meet the family’s younger generations, Christophe and Catherine and their daughter Coleen Celia Gaudin-Boutringain in Paris.

Hasbrook put together a book of photos and text so others could know this story. And now you know it, too.

Kerry Temple is editor of this magazine.