We treasure it. We obsess over it. We seek it out with all our might. Yet because none of us can ever gain even the tiniest fraction of a second more than we are allotted, we try to manipulate time, to distort it and disguise it, foolishly imagining that it responds to our commands.

And, oh, how we try. We foreshorten time so the Christmas season now starts just after Labor Day. We stretch it out, and that AARP membership card now automatically comes in the mail when we hit 50. We become impatient with it, rallying for a turnaround after a two-game losing streak or pleading for the end of a cold snap after just a single day of frigid temperatures. To our fractured senses, time drags at certain moments and at other moments, it flies.

Nature doesn’t treat time anywhere near as cavalierly as we do. She is a precise timekeeper, marking seasons from year to year. And nowhere is that clearer than in the time testaments found in the annual growth rings of trees.

It has been only over the last half century or so that trees have started to surrender their ancient secrets. We now have virtual tree ring calendars that can tell the unvarnished history of our earth, year by painstaking year. These rooted annals of time divulge patterns of rainfall and temperature over millennia, bookmarking massive climatic swings and disruptive geological events.

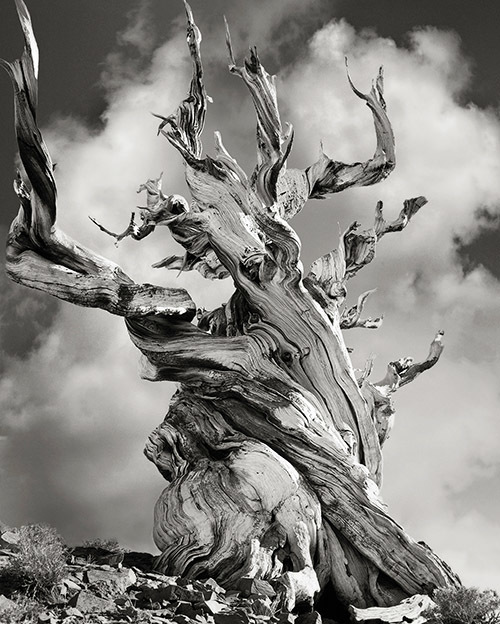

We have long revered the towering redwoods and the majestic sequoia because their tremendous height or ponderous bulk suggest a passage of time far greater than our own. But the real champions of time are not nearly as well-known. Discovered in the middle of the last century, they are far from giants. The Great Basin Bristlecone Pines, Pinus longaeva, rarely exceed 30 feet in height. By mass, they only occasionally reach a girth that is at all impressive.

Yet these ragged but regal survivors have a remarkable ability to provide sobering testament to the raging storms and withering droughts they have lived through. Seeking knowledge of the past, scientists bore straight to their innermost hearts to extract pencil-thin cores. Reading those samples, they now know that many of these trees have been growing in one remote and inhospitable region of the White Mountains of California for more than 5,000 winters, an unimaginably long time for a single living thing to have existed — taking in nutrients, warding off the elements and producing offspring. When the first stones of the pyramids were laid in the sands of ancient Egypt, the trees were already stretching their branches to the heavens.

Some see trees as imperfect men that curse their paralysis in the soil. The naturalist John Muir disagreed. So do I. To me, the strangely beautiful bristlecones are as serene as Buddhist monks, filled with a kind of spiritual wisdom derived from their age. They can tell us much more than the weather, narrating sagas of life, adversity and the will to survive, if only we make the effort to listen to them. In my life I have done so twice, first when I was a young man, and four decades later, when I was not. Both times, and in all the years in between, the secrets of their inner selves have claimed a place in my heart, providing a steady lesson about not just my life but about all life.

I first heard about bristlecones when I was an undergraduate. Finding out about them was as serendipitous as it was incongruous, for I grew up in a cloistered Northeastern city down on its luck. Ours was a working-class home, with a loud TV, coats hung on a door rack and no books except for those we brought from school. But the local newspaper was delivered six afternoons a week, and in a daily ritual my longshoreman father would return from the Hoboken docks, remove his heavy black work boots, snap open the broadsheet and lay it across our dining table to read — the only reading I ever saw him read.

That vision of him with the daily paper instilled in me an enduring love for the power of the printed word. And when he was finished with the paper, it was my turn. It was while reading it one day that I found, perched above a large advertisement, a headline containing the hypnotic words “world’s oldest living things.”

I’m not sure why that phrase captivated me. At that point in my life I knew almost nothing about either nature or the environment, and I certainly wasn’t old enough to be concerned about age. I hadn’t yet turned 21. I had never seen a wild animal larger than a squirrel. I couldn’t for the life of me name the lumpy trees in the worn-down city park a few blocks away or the spindly one that somehow managed to grow in the hard-packed dirt of our cramped backyard.

They were just trees.

But at that time I was struggling to find out who I really was and to create the person I thought I wanted to become. When I entered my senior year in college, I had to live away from home for the first time in my life because I had won an internship at a television news operation in Trenton, New Jersey. Working there to put together a nightly newscast gave me my first inkling of the extent of the world that existed outside my own.

The internship ended with the academic year, but working had delayed my graduation for two semesters, giving me the opportunity to embark on what then was considered a rite of passage — a coast-to-coast road trip. I had already laid the groundwork for such a trip, purchasing a battered 1963 International Harvester Scout — a stripped-down, blue-collar precursor to current SUVs. The Scout came with a three-speed manual transmission, balky vacuum-powered windshield wipers and four-wheel drive that could be engaged only by hopping out to turn dials on the front hubs.

All I needed was a co-pilot, and I didn’t have to go far to find the ideal one — an Air Force veteran and pre-med student at my university, Charles Carodenuto, who hadn’t heard of the bristlecones but was ready for the adventure.

Our goal, roughly, was to reach the bristlecones. The article I had clipped from my local paper described them as growing outside the city of Bishop in the White Mountains of California, so Bishop became our destination. We made no reservations. We had no Siri or Google Maps to guide us. A single Motor Club of America book of maps was all we had, backed by a youthful innocence that assured us we would be all right. It was the summer following the first Arab oil embargo, and our main worry was how far we could get on our combined budget of $500 with gas at 59 cents a gallon, nearly double what it had been just a year before.

I, an aspiring writer, was intent on recording this voyage of discovery. I had with me a 69-cent three-subject Nu spiral bound notebook that by then was half filled with ramblings dating back to high school. On the day Charles and I took off, June 4, 1974 — two weeks before my 22nd birthday — these were the first presumptuous words my naive self wrote:

“Away. Away. Just get me away. A slow tear is not good. It is painful and lingering. Rip me apart. Get me away. Happy — but not happy.”

What I felt was the anxiety of separation, leaving behind not just home but the life that was expected of me, the path of my father and my three older brothers, the expectations of the people around me who were born, lived and died in that gritty city. Charles and I didn’t know exactly where we were going, and we didn’t know how long we would be gone. But we understood how sharply we were breaking with our pasts and tempting the future.

When we headed out, we did not have a tent. We had no credit card. We knew we could overnight in the Scout if we had to, but we intended mainly to sleep outside, wherever we happened to be. We set out for the closest national park we knew about: Shenandoah, a rustic and beautiful series of ridges in Virginia. Then the Smokies, and across to Arkansas. On day XV (I marked the days with Roman numerals, as if that underscored their importance), we crossed the Mississippi and I marveled at what I had never seen before: stars in the night sky that appeared in the side windows of the Scout.

“Big sky,” I observed in my journal. Back in Hoboken the star sky was limited to the narrow spaces between buildings. But this, this was something to fill one with wonder, to raise sights and spirits, to place into context what was, and what was yet to be, a voyage not unlike the one taken half a century earlier by another city kid who had no reason to be enchanted by trees but was. And that brought him, as it did me, to the bristlecones.

Edmund Schulman was as unlikely a tree whisperer as I was. Born in Brooklyn in 1908, he grew up in the dense urban forest of New York with as little opportunity to encounter nature as I had. Sickly, short, with plenty of smarts but not a lot of money, he started college in 1927 but dropped out when finances got scarce. He returned to work, toiling unhappily in sales while fantasizing about pursuing his real dream, which was not yet trees but stars.

It took a few years but Schulman went back to school, enrolling at Brooklyn College with the intent to study astronomy. But when doctors found that he was developing tuberculosis, he pulled together what money he had and bought a ticket to Denver, hoping the city’s altitude and dry climate would help. When he could not find work there he moved on to Flagstaff, Arizona, with a vague notion of working in the Lowell Observatory. There was no job for him there, either, but he found out that in-state tuition was cheap. He made contact with A.E. Douglass, the head of the Steward Observatory in Tucson, and pestered him enough to eventually be accepted into the University of Arizona and Douglass’ popular class in tree-ring interpretation.

Douglass’ research then was focused on linking solar cycles to changes in the earth’s climate. He theorized that the 11-year sunspot cycle was tied to specific climate patterns. He had learned that studying the growth rings of trees was a way of identifying past weather conditions. The calculations are rather straightforward: The wider the growth ring is, the better the weather and the growing conditions that year. That record could then be correlated to the activity of the sun.

The astronomer is now widely considered a pioneer in the science of dendrochronology, the study of tree rings. One way of looking at it is to consider dendrochronology the scientific equivalent of reading a calendar backward, peering into the very first year that a tree — no matter how old — began its life.

Douglass was never able to convincingly prove his hypothesis about solar cycles. But the basic science of reading tree rings to determine climate conditions turned out to be remarkably reliable, particularly as that record has been extended back several millennia.

Soon after arriving in Tucson, Schulman dropped his interest in the stars and devoted his time and energy to trees, working with Douglass and others at what became the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research. There they refined methods of sampling the trees and reading the rings. Naturally, they also searched for the oldest trees with the longest records.

Fortunately for Schulman, the west is inhabited by some really big, really old trees. The stumps of the giant sequoia harvested in the 19th century routinely contained 3,000 rings. But their range was so limited that it was difficult to use them for cross-dating, which is the process of lining up the ring patterns of living trees with far older specimens, often those taken from Native American cliff-dwellings in the southwest, which extends the record far into the past.

Schulman came across Ponderosa pines that he could accurately date back to 1090 A.D. and a juniper in the Yosemite Valley that was around 2,000 years old. As word of his quest for old trees got around, he received reports of unusual trees in the Big Pine, California, area, which is nestled between the Sierra Nevada on the west and the White Mountains on the east. In the early 1950s, the forest ranger in that section, Al Noren, had come across some unusual trees called bristlecone pines. Their needles were arranged on their branches like bottlebrush bristles, and some people thought they looked like foxtails. Bristlecone wood was dry and dense, and when Noren collected some for woodworking projects, he casually started to count the rings and was surprised the wood seemed to be more than 1,000 years old.

In 1953, Schulman set out to see the bristlecones for himself. On a hastily organized excursion that fall, he wandered among the trees, using a Swedish increment borer to drill into their hearts to remove core samples that, like X-rays, allowed him to see the tree inside out without harming it.

Schulman later recalled inspecting those samples by the light of a campfire lantern. He called it an epiphany. He counted, and counted, and counted until he had counted more than twice as many rings as he’d expected to find, more than 4,000 in all.

On September 30, 1956, The Arizona Republic ran a front page article touting Schulman’s startling discovery of the oldest living thing on Earth, which the paper described as “a scrubby little pine tree” more than 4,000 years old. The news made the bristlecones instant celebrities and launched Schulman into the pages of the popular press, as well as into scientific journals.

He continued to scour the ancient bristlecone forest for trees that were even older. On a hillside a few miles beyond and about 1,000 feet lower in elevation than the area known as Patriarch Grove, he began test borings on several tall, straight bristlecone pine trees. He assumed that, like the redwoods and sequoia, the larger the tree, the older it must be.

He soon learned the opposite was true. The tall trees turned out to be relative youngsters, a couple thousand years old but nowhere near as old as the ancient ones he’d already identified. He kept testing and eventually concluded that it was the twisted and stunted trees, those partially dead ones with tortured limbs, which were older, much older. These findings helped him formulate a theory he called “longevity through adversity,” hypothesizing that areas that were less than optimal — tormented by frequent drought, high winds, severe and prolonged cold, and soil that was nothing more than chunks of pale dolomite rock — actually enhanced the trees’ fantastically long lives.

In that grove, Schulman found several trees older than 4,500 years, and one he called Methuselah that is estimated at more than 4,800 years old. He soon began work on a popular article for National Geographic that would greatly expand awareness of the bristlecones and trigger widespread wonderment about the meaning of time, of age and of life.

Tragically, the discoverer of what then were considered the “world’s oldest living things,” did not live to enjoy his renown. Schulman suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage while working on the University of Arizona campus and died on January 8, 1958, just weeks before publication of his National Geographic article. He was only 49 years old. But his work, and the secrets of the bristlecones, have had an enduring impact on science. The living trees, along with wood from long-dead trees, have created what is called a “master chronology” that now stretches back to 6731 B.C. — an unbroken record of more than 8,700 years. The bristlecone wood is so accurate a manuscript of time that it was used to recalibrate and correct carbon-14 dating techniques, and forced archaeologists to rewrite parts of the history of mankind.

Today, the section of the forest containing the oldest bristlecones in the White Mountains is formally known as Schulman Grove. And that’s where Charles and I arrived on Day XXXIII of our own journey in 1974.

It had taken us more than a month of hard driving in the rattling Scout to reach the bristlecones. Once we arrived, I had no ceremony planned and nothing I intended either to leave there or take away when we left. It seemed to me that overcoming the great improbability of the two of us — long-haired street kids from Hudson County, New Jersey — actually making it to that remote spot on the other side of the continent, a place no one at home had ever heard about, was sufficient to make simply being there an event.

It is a vast understatement to say that I had never seen anything quite like those trees. Each one is a community in itself, not a single trunk like other trees but a collection of individuals sharing the same root system but not necessarily all sharing the same roots. Several impressions about the ancient forest manifested themselves right away. One was the quiet. At 10,100 feet elevation, the air felt thin, the light almost evanescent, casting a heavenly glow around the trees.

No animals were in sight. No people either. There was no visitor center, no ranger station. Only a couple of portapotties, a drinking water fountain and a wooden box on a post containing folded paper brochures. I still have the one I took. Here’s what it said: “High on the wind-swept, rock-strewn slopes of the White Mountains, northeast of Bishop, California, are the oldest known living things in the world . . . the amazing bristlecone pines.” That was all I needed to read, a statement of affirmation proving I had come to the place I had sought.

“Walking through the bristlecones, one doesn’t feel old,” I wrote in my journal. The date was July 7, 1974. “Instead, I feel a new reverence for life, all kinds of life. And I feel a new respect for the right of all things to continue their lives — in the ways they may choose — without interference.”

But why would a 22-year-old go through such effort to be in the presence of something so unimaginably old? I hadn’t worked that out in my journal. A 22-year-old doesn’t necessarily need a reason for doing such things; that is the privilege of youth. It is up to me now to try to interpret my own actions, and I think what it comes down to is that this was my way of making a pilgrimage, which was the only way of traveling I knew of back then.

You see, my parents did not take vacations. There wasn’t the money, on a longshoreman’s income, nor was there really the desire. My mother and father both were born in Hoboken and remained rooted there, within the same few blocks, their entire lives. There was such a spread in years of their six children (my eldest brother is 14 years older than I am) that I don’t remember us all living together, and we certainly never vacationed together.

I was the fifth of the six, and by the time my younger sister and I were teenagers, Mom and Dad had settled deeply into their routine. That ordinariness was interrupted only once when our next-door neighbors — my best friend, Nicky, and his parents — invited us to accompany them on their annual trip to the shrine of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré in Quebec, Canada.

I believe Nicky was one of the last people in the United States to be struck down with polio. To compound his misfortune, he had been born with hemophilia, a double whammy that left his Italian-American parents reeling. Nicky and I were constant companions except for a week each summer when his parents loaded his wheelchair into their black Pontiac and headed north to St. Anne’s. The year we went with them I was awed by the huge basilica and by the mass of braces and canes spiraling around the columns inside the entrance. Nicky explained that one of his earlier metal and leather braces was strapped up there, a testament to the miracle that he and his parents believed would allow him one day to walk.

I suppose now that traveling to the bristlecones was equally a pilgrimage for me. It was not a miracle I was seeking but rather a substantive change in my life, a departure from my insulated existence and a passage to a world of greater meaning. My aspirations of becoming a writer were wrapped up in a deep desire to make my life matter, to live as though my existence meant something. Touching the bristlecones was, to me, like praying at St. Anne’s. I was hoping that physically being there would transfer some intangible benefit from the trees to my innermost self. Immortality? No, except perhaps through words.

Schulman thought the bristlecones’ uncanny ability to stay alive held secrets that someday would lead to breakthroughs in extending human lifespans. So far there’s been no evidence his theory was anything but a hunch.

Because I did make that trip at 22, I have been able to do much more than I had ever imagined. For me, visiting the bristlecones — the ancient ones — was, in every respect, a liberation.

I know now how significant that encounter was because afterward I was able to understand both the life of trees and the existence of man far differently than I did before. I comprehend now that there are no annual rings inside of us, nothing that records the passage of years the way the bristlecones do. Nothing that bears the mark of the shifting environment — the lean years and the fertile ones, the times when we grow and those when, unable to progress any further, we languish. The trees show us how to live noble and honorable lives, not only respecting our environment but accepting it for what it is and not making extraordinary demands of it. It is an important lesson in how to turn adversity to advantage. How one part of us may suffer but the rest goes on living.

I knew that the trees, by their unending struggle to live, were special, and I suppose I was hoping to find out how to achieve at least some aspect of that quality in my life. But once I stood in their immutable presence I began to realize it wasn’t just their long lives that made them outstanding. I learned that the cells of their growing cambium layer are packed so tightly that a hundred of their famous rings can be contained in a single inch. And the bristlecone is stuffed with a powerful resin that makes the wood extremely resistant to rot and insects. I learned that the trees live so long that they can exhaust the nutrients in the rocky soil below some of their shallow roots, and when that happens they can shut off the parts of the tree supplied by those failed roots while the rest of the tree keeps growing. That process led Schulman to label the bristlecones “living ruins,” which do not necessarily live forever but take thousands of years to die.

I also learned that the adverse conditions in which the trees grow actually add to their long lives. Their region of the White Mountains is often described, accurately, as a moonscape. There is no soil to speak of, just densely packed shards of dolomite rocks the color of bones, so lacking in nutrients that only bristlecones grow there. Competition for scarce moisture thus is quite limited. There are other advantages, too. Lightning fires do not rage because there is no groundcover or brush to feed them. The weak soil also restricts propagation, which leaves plenty of empty spaces in the ancient forest, further isolating the trees from fire and infestation.

“Monuments to the will to survive,” I wrote while in their presence. “Standing in the same adverse field of domolite [no spell check then] stone — dry, windy, cold — they have been there for all the time that mankind was recording its puny history. They live where few others can. And they live so long because when a part dies, they let it die, and continue growing on another side.”

The light at the top of the mountain intensifies the colors of the ancient forest in a striking way. The predominant hues are not green and brown, as in other woods, but sunwashed gray and a deep, burning ochre that shines like copper. The trees last so long that the dead wood is blasted by wind-driven sand into fantastic slippery shapes that rise to the sky like arms raised up in prayer, the burnished tints deepening as the sun sets behind the barren mountain tops.

As Charles and I sat to watch that extraordinary day end, a cloud in the deep blue California sky shifted shape in front of us. It appeared to form a profile, and I thought for a moment how strange it was that the cloud looked like the reflection of a man.

Charles said it looked like me.

That trip did mark a turning point, at least for me. Charles went on to study medicine, becoming a successful family practice physician in Minnesota. He never mentioned the trees again. What followed for me was a life far different than what I had ever imagined in Hoboken — a career in journalism that has presented opportunities to take part in a world that knows few boundaries. With my wife, Miriam, and our children, we have lived in other countries, traveled to places few others get to see and managed to make friends who are as dear to us as family. We’ve had our share of setbacks, too, tragedies, illnesses, disappointments enough to stagger.

Through it all I have never forgotten the bristlecones. At home I hang a photograph of the trees that I took on that trip with Charles, and I have retold countless times the story of visiting the oldest living things, even when I had to adjust the wording after other, long-lived organisms were discovered.

Finally, in 2014, 40 years after my initial foray into the Whites, I was able to return to the ancient forest. This time, after hearing about them so often and seeing their photo on the walls of each of our homes all those years, Miriam came with me.

This time, I didn’t drive from the East Coast. Instead, we flew to Arizona and rented a car there, using a Garmin GPS to find our way first to the Grand Canyon and then west through Death Valley into California, essentially retracing part of the same route Charles and I had taken in the Scout. With credit cards in my wallet, we stayed at a hotel in Lone Pine, California, which had a table in the lobby made of heavily shellacked bristlecone wood, and prepared to ascend the mountains into the ancient forest.

Early the next morning we drove north through Big Pine and turned east into the White Mountains, climbing steadily toward the forest, 40 years and one month after the last time I was there. At 10,000 feet we found a large parking lot and a new visitor center that replaced one built after my first visit but destroyed in 2008 by an arsonist who did not tolerate the idea of big government controlling the trees. The visitor center had not yet opened for the day so we simply took our walking sticks and headed out on a trail through the Schulman Memorial Grove.

“It leaves me breathless,” I scribbled in a notebook as we made our way past some of the younger trees that we later learned were more than 3,000 years old. I was struck almost immediately by the thought of how much I had changed since I walked among these trees and how the trees had hardly changed at all. In truth, as I later discovered, these astonishing trees grow so slowly that many of them likely still bore the same five-to-a-stem bottlebrush pine needles they had in 1974, the average life of those needles being not one year, as in most evergreens, but 40.

Scientists, including some at Notre Dame, continue searching for answers about how these trees manage to do what they do for so long.

I was struck, too, by the memory of how Miriam and I had struggled to reconcile ourselves to cutting down an elderly sugar maple on our property that had not leafed out the previous spring. We had counted the rings after the great tree was felled and were saddened to find 147 of them. We mourned the loss for weeks.

Suddenly that tree seemed not old at all. Time had shifted again.

The high mountain forest of the bristlecones evokes the passage of time on a vastly different scale, one more closely resembling the way the Grand Canyon reveals the different stages of the earth’s existence, layer by layer, back through time. But the fact that we share with these trees the concept we know of as living — they respire, they require nutrients, they bear offspring and they need to find a way to not merely persist, the way a stone can, but to survive, the way we must — imbues them with significance that inanimate monuments, no matter how grand, never can possess.

All that morning we passed only one person on the trail, and we did not see Methuselah, the oldest of the old trees, because it is not marked. Neither is one that was found in 2012 to be 5,062 years old. We read that the trail has been moved to protect them, but from what? I suspect it is not because of the arsonist who destroyed the visitor center in 2008 but instead those who would love the tree too much and who, despite many admonitions not to, would want to bring home a piece of the oldest tree, just as they would a piece of the real cross.

“Their existence is a constant reminder of the fleeting nature of our own time on earth, how very, very short is our time here, and how important it must always be to revel in and take advantage of every moment,” I wrote in the latest edition of my journal, this time without any Roman numerals or overheated prose. Referring to the trees I was greeting again like old friends, I wrote, “they scold us for allowing adversity to stand in our way instead of adapting to it, and turning it to our advantage. They show us how, when one part of our lives comes to an end, we need to send nutrients in another direction where the strength we gather can overcome the loss.”

The bristlecones have provided inspiration to last an entire career, and I continue to look to them for more. I wrote: “Their impact on me will not end now. It will be strengthened and redoubled, providing the rationale for more dreaming. The great distance I have traveled since last I was here will pale in comparison to the distance I have yet to go. The memories of today will direct and complete all of them.”

Edmund Schulman thought the bristlecones’ uncanny ability to stay alive held secrets that someday would lead to breakthroughs in extending human lifespans. So far there’s been no evidence his theory was anything but a hunch. The cells of the bristlecone do age — the scientific term for it is senescence — but at an extremely slow pace. The oldest of the trees may still bear sticky purplish cones (I have one sitting on a slab of dolomite on my desk now), but those cones do not sprout healthy new individuals as reliably as when the trees are younger.

These remarkable trees produce no secret elixir, nor do they have any DNA oddity that can be isolated and replicated to prolong life. Their real promise is not in prolonging our physical lives — as I wrote earlier, no matter who we are or what we do, we have no more time than we are allotted. Rather, the secret the ancient ones whisper to those who listen is not in how long we live, but in how we live.

Scientists, including some at Notre Dame, continue searching for answers about how these trees manage to do what they do for so long.

Adrian V. Rocha, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, describes himself as an ecosystem physiologist whose work focuses on the way trees grow. He grew up in California, and when he was about the same age I was when I met the bristlecones, he headed into the Whites to meet them. He visited the ancient forest a second time in 2004 when he was completing his doctorate.

Rocha considers the bristlecones “pretty amazing trees” that have adapted to living in an extreme environment. He, like Schulman, considers them permanently old and always dying. “Plants have two different strategies,” he says. “Live fast and die young, or live slowly and die old. These trees really employ the latter.”

That’s the science of it. But Rocha also is sensitive to the spirit of the bristlecones. When I ask him to exchange his lab coat for a philosopher’s robe, he’s willing to answer this question: What can we learn from these magnificent beings and the method of their living on this earth?

“Not speaking as a scientist now, I think there’s a knowledge that these trees have about where nutrients are, and they think ‘I’m going to put roots there,’” Rocha says. “It’s not a conscious decision, but you have to think that to live so long they have to develop a much better knowledge of the environment and how changes evolve, and then know how to take advantage of those changes.”

Since my first awareness of the bristlecone pines in my local newspaper (the same paper where I received my first professional byline), I have continued to explore noble trees and the concept of great age. While I worked as a foreign correspondent in Mexico, I traveled to the state of Oaxaca to see the incredible Tule Tree, a 2000-plus-year-old cypress so large that tradition says when the conquistadors arrived, a lightning strike had created a hole in the trunk large enough for a Spaniard on horseback to ride through. When I reported on the tree for The New York Times, I learned it was so revered that a visitor had carved into its trunk the words “God, you are a tree.” Sometime later, an equally awed visitor who stood humbled in front of the great tree scribbled on it, “Tree, you are God.”

I’ve written about the hardy American elms in Princeton, New Jersey, which somehow managed to survive the blight that nearly wiped out most of the elms in this country. I’ve done stories on more recent plagues such as the Asian longhorned beetle and the emerald ash borer that are killing millions of hardwood trees in the United States.

And I had a chance to correct the record when I wrote about the box huckleberry, which has been growing on the same hillside in Pennsylvania for an estimated 10,000 years, easily surpassing bristlecones as the world’s oldest living things. But a bit of explanation is in order. The huckleberry is a not a single plant but a creeping ground cover that grows by cloning itself. There is nothing like a tree ring in these plants. Instead, scientists calculate the age as a factor of the rate of reproductive growth. The plant creeps along at a rate of about 6 inches per year. The Pennsylvania huckleberry patch covered more than a mile until a significant portion of it was hacked away to widen a road leading to the Penn State football stadium.

Although the huckleberry may currently bear the crown as the world’s oldest living thing (other clonal species are now in the running), I assure you that standing before the huckleberry is nothing like touching the exposed grain of a bristlecone whittled down by wind and time, or standing in the shadow of its gnarly stele on an unexpectedly cool August evening, or shielding your eyes from the glare of the pale dolomite crags that shimmer in the summer heat as though baking the trees’ cones and needles. Those images, indelibly embossed on my mind, will forever inspire me to stand up to adversity.

Recently I was introduced to the words of Pema Chodron, a Buddhist nun, and something she said about adversity ties in evocatively with what the bristlecones have taught me. It is a lesson for every student, every parent, every teacher, every young person and every one of those who no longer call themselves young.

Chodron wrote about what she says is a common misunderstanding, the mistaken belief that the best way to live is to avoid pain and adversity. The more enlightened way, she proffered, is to endure pain and pleasure “for the sake of finding out who we are and what this world is, how we tick and how our world ticks, how the whole thing just is.”

Most people don’t buy that. They are committed to comfort at any cost, even though by doing so they stand to lose more than they gain.

“As soon as we come up against the least edge of pain, we’re going to run,” Chodron wrote, and doing so inevitably alters the course of our lives. “We’ll never know what’s beyond that particular barrier or wall or fearful thing.”

Her words seem to echo the lesson of the ancient bristlecone pines, organisms that thrive on adversity with such spectacular results. It is a good lesson, I think, for facing squarely all the challenges in our lives, both those we cannot avoid as well as the ones we sometimes choose, of our own volition, to chance, in the hope of finding out who, and what, we really are.

Anthony DePalma, a former visiting fellow at Notre Dame’s Kellogg Institute for International Studies, is the author of several books, including City of Dust: Illness, Arrogance and 9/11. A regular contributor to Notre Dame Magazine, his most recent article, “Blessed Are the Quiet Heroes,” appeared in the spring 2013 edition.