At age 83, Paul Fenlon had lived in Sorin Hall for over 60 years, but in February 1980 his failing health had prolonged his Christmas holiday with his family in Pennsylvania. He complained to me on the phone about his increasing frailty, sounding resigned never to return to campus.

Fenlon was the last living link to the great tradition of Notre Dame bachelor dons. A colorful array of scholars, eccentrics and dandies, the dons were unmarried faculty members who lived in the residence halls. Many were popular with students, counseling and befriending them. Their heyday was the 1920s, when a quarter of Notre Dame’s lay faculty lived in dorms.

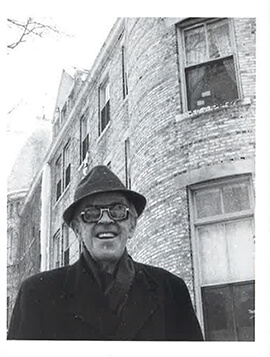

Photos Courtesy of Philip Hicks

Photos Courtesy of Philip Hicks

A generation later, their numbers plummeted when a decision was made to move everyone off campus with the exception of four stalwarts — Jim Withey ’26, Joe Ryan ’24, ’41M.A., Frank O’Malley ’32, ’33M.A. and Paul Fenlon. By 1974, with Ryan moving off campus and Withey and O’Malley both dead, Fenlon was the last of the dons.

A native of Blairsville, Pennsylvania, 40 miles east of Pittsburgh, Fenlon enrolled at Notre Dame in 1915. After his graduation in 1919 and an unhappy stint as a banker in Chicago, he returned to campus in 1920 to teach and live in Sorin. His dramatic readings in courses on the short story and the Victorian novel made him a popular English professor, and, after 42 years in the classroom, he worked for a time in the alumni office.

As a freshman in 1976, I met the man we called “the Professor” when he was scouting the first floor for someone to wind his watches. He was a tall, slender figure with wire-rimmed glasses and thinning white hair brushed straight back. His lanky frame, long face and especially his voice, with its hint of a drawl and slight singsong, reminded me of Jimmy Stewart, the movie star who grew up near Blairsville.

Fenlon invited me to drop by for a chat. He lived in Room 141, the turret nearest Sacred Heart Church. On my first visit to his room, it was just as I had imagined — a time capsule from the 1920s stuffed with musty furniture, littered with bric-a-brac and photographs and books in green and brown hardcovers with slips of paper and letters secreted between their pages.

I learned that famed English writer G.K. Chesterton attended Fenlon’s bootleg beer party in Sorin during Prohibition, that future U.S. Secretary of State Alexander Haig came to him for his allowance, that longtime bachelor don William J. “Colonel” Hoynes read the dictionary with a magnifying glass under a bare lightbulb as young Fenlon spied on him from the Sorin porch.

My visits, motivated at first by my curiosity about the hall’s history, usually began late, after the library closed. His door was always ajar and he would be at his desk. He’d swing around, get me into focus through his thick lenses, smile and say, “Good!” as if I’d just accomplished something important. There would be a folded newspaper propped up on his desk, or a magazine opened to a certain page. “Here,” he’d say, “I’ve got something for you.”

Our conversations ran the gamut of campus gossip, politics, family news, sports. I usually steered the discussion back to historical topics, trying to pin down the tiniest details. This sometimes left him with his hands cupped over his eyes, blurting out, “You ask the damnedest questions!”

What I liked was how easygoing he was. He didn’t tell me what to do or how to think. He valued the give and take of a good conversation, resisting the temptation to become a guru.

In retirement, Fenlon’s days began early with Eddie the janitor bringing him the paper. He’d arrive at Sacred Heart’s 11:30 Mass late enough to miss the homily. “They’re too long,” he insisted, “and I usually don’t like what they say.”

He returned to paperwork or reading after lunch. Three o’clock tea was a tradition borrowed from former bachelor don T. Bowyer “Tea Boiler” Campbell. At cocktail hour he took his scotch before heading off to dinner at the Morris Inn, the University Club or in town with friends and their wives, or with Tom Stritch ’34, ’35M.A., another ex-don, or with an assortment of faculty widows.

Photos Courtesy of Philip Hicks

Photos Courtesy of Philip Hicks

Later he’d settle down with a novel or magazine like Time or The New Yorker until bedtime, when he visited Sorin Chapel. In his pajamas and robe, he shuffled up the aisle saying his rosary, stopping at the altar, then walking backwards so as not to turn his back on the tabernacle.

These routines brought him great joy. Yet he also faced numerous trials, each contributing to an intolerable burden of anxiety. For starters, he had enemies. Who were they? Administrators? Faculty? Priests? He wouldn’t say, but to hear him tell it, he might at any moment find himself on the sidewalk, his possessions piled around him.

The carnival funhouse of Sorin couldn’t have been easy on his nerves. Firecrackers exploded at all hours — dropped from tower windows, set off in hallways, shoved under the rector’s door during staff meetings — and the “Sorin Seven” ran a bar on the third floor. Marijuana use was common and parietals were broken with impunity.

The sex and drugs didn’t seem to bother Fenlon, but the rock ’n’ roll sure did. He despised noisy horseplay, tracking down the worst offenders and confiscating their balls and Frisbees.

When his best friend, Rev. Daniel J. O’Neil, CSC, ’46, the former rector of Walsh Hall, became sick, Fenlon’s own health began to suffer. He developed insomnia, irritability and strange aches and pains.

Despite these ailments, he could always rise to the occasion for visitors. He helped an old friend, Chet Grant — Knute Rockne’s quarterback in 1920 and 1921 — look for the room he had once shared in the Sorin Subway with Harry Stuhldreher of Four Horsemen fame. The two octogenarians had to roust several residents from their naps in what became a comic goose chase.

Though such visits provided welcome relief, Fenlon’s anxieties caught up with him. In line for communion one day, he buckled at the knees, fell into a pew and was rushed to the hospital.

A month later, Fenlon had recovered from his “fidgety attack,” but Father O’Neil had succumbed to cancer at age 58. For Fenlon, friends might die, but friendships never did. He kept his deceased friends in his prayers, observed their anniversaries at Mass and honored their funeral cards on his desk. Even in ordinary social interactions, he refused to concede a permanent break: “I only say ‘so long.’ I never say ‘goodbye.’”

Not long after O’Neil’s death, Fenlon fell off the steps in Tom Stritch’s backyard and cracked his pelvis. He spent three weeks in the hospital. Too fragile to go back to Sorin, he was moved to the Student Health Center. He didn’t like it — not the schedule, not the rules, not even the name, a detestable euphemism for “infirmary,” he thought. Characteristically, he organized a clandestine cocktail party for his student friends and charmed the nun in charge of the center’s no-alcohol policy into joining us.

After six weeks he returned to Sorin for the rest of my junior year, but over the summer in Pennsylvania he suffered a mild stroke. When he returned to campus the fall of my senior year, he had to go back to the infirmary, where he remained until flying back to Pennsylvania for Christmas.

Two months later, he called to say he was going to live out his days with his niece, her husband and their young son. Sorin wasn’t a realistic option any more. Then, 20 minutes into the call, he made an abrupt about-face. “What I’d like to do,” he said, “is come back during your vacation this Easter, then stay through for your commencement. Then we will all go out together.”

That April he flew back to South Bend. Special accommodations had to be made for his return to Sorin. University President Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, issued the order to do everything possible to make Fenlon happy.

The welcome was so successful that Fenlon decided to stay in Sorin indefinitely. In this bittersweet period, when everyone was trying to make the most of the time they had with him, the two of us spent an afternoon on the Sorin porch. He was happy and relaxed, taking in the spectacle of students playing and shouting on the quad. Residents stopped to chat. Several passersby waved as a wedding let out of Sacred Heart. One fellow came up and said, “The last time I saw you, you were sitting on the same spot, 40 years ago!”

Paul Fenlon died November 7, 1980, after a series of strokes forced him off campus to Healthwin Hospital. Conscious but robbed of speech, he was listening to my friend John Sweeney ’80, ’84M.A. read poetry when he passed away.

He lies in the Holy Cross Community Cemetery, two paces from fellow don Frank O’Malley. Three rosaries are draped over Fenlon’s cross. The first one appeared a decade ago, the second a few years back. I added the third.

Philip Hicks is Bruno P. Schlesinger Chair of Humanistic Studies at Saint Mary’s College. He is writing a book about Paul Fenlon.