James W. Frick died April 9 at his home in Naples, Florida. He was 89. His death is one of those that makes you lean back in your chair and gaze out the window. It’s hard to bring such a life into perspective. And at Notre Dame you would never say that Jim Frick has passed away.

Jim Frick graduated from Notre Dame in 1951 and immediately joined the University staff — the first full-time employee devoted exclusively to fundraising. He was also the first staff member to seek donations beyond campus. He talked the Holy Cross fathers into letting him do a test trip to Milwaukee, where he lined up 15 appointments over three days.

Frick chose Milwaukee, he later recalled, “because it’s a fair-size city, yet not as big and frightening as Chicago or New York, where I felt I would get eaten alive.” His first stop was the office of Fred Miller, Class of 1929, who had coached under Frank Leahy and also ran a beer company. “I went to Fred’s office,” Frick recounted. “I was very frightened; my knees were shaking. I began to wonder why in the world I was there. The secretary ushered me into the office. It seemed like 300 yards from the door to his desk.” Miller and Frick talked, and Miller — “who realized with one sentence he could have destroyed me” — wrote out a check for $2,500.

Frick, who became one of the nation’s most renowned development officers, never forgot Miller’s kindness. Throughout his career he insisted that fundraising was essentially about relationships. “I walked out of that place about three feet off the floor,” he later explained. “That was exactly what I needed. Fred Miller knew this, and I will forever be indebted to the man for his understanding.”

The 28-year-old returned to campus with $12,500 (“a tremendous amount of money in those days”) and walked into the office of Rev. John H. Murphy, CSC, who was “absolutely amazed.” But the priest reneged on the pre-trip deal he had offered Frick — that he keep 10 percent of whatever he brought back.

Frick became Notre Dame’s director of development in 1961 and four years later was elected vice president for public relations and development, the first lay officer in the University’s history. “Jim Frick took over a fledgling development organization and turned it into one of the most successful fundraising operations in the nation,” said president emeritus Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, shortly after Frick’s death. “Few individuals have left the University more in their debt than he, and few have had a more decisive and widespread effect on the history and development of Notre Dame.”

Frick did not just create and then lead the development operation through a series of enormously successful fundraising campaigns. He was in charge of University communications, public relations and publications, a burgeoning Alumni Association, and the news and information office. He also was instrumental in the creation of Notre Dame Magazine in 1972. It was a radical departure from traditional alumni magazines, and he stood by its independence on those occasions when content drew criticism. He did, however, trade that editorial autonomy for an adherence to high-reaching standards.

Frick was also at the table for the historic deliberations and decisions of the Hesburgh administration. The story goes that when Hesburgh offered the vice presidency to Frick, he warned the priest that he would speak his mind, even if it meant disagreeing with the iconic president. To which Hesburgh was said to have replied: “Jim, if you were to be a ‘yes man,’ then one of us would be redundant.”

At the outset of the Campaign for Notre Dame, the ambitious fundraising drive of the 1970s, Frick told Hesburgh he could not ask others for money if the two of them had not donated first. The priest reminded Frick that he had taken a vow of poverty. Frick pointed out that Hesburgh had income from books, honoraria, lectures and consulting fees, and suggested $50,000 as an appropriate contribution. Like thousands of others, Hesburgh responded to Frick’s appeal and made his pledge.

The advances Notre Dame made during the Hesburgh era turned heads throughout higher education and beyond. Most Notre Dame people knew the role of Rev. Edmund Joyce, CSC, the executive vice president, in managing the budgets and overseeing the physical plant during the Hesburgh years. But it fell to Jim Frick to raise the money that propelled the Hesburgh revolution.

Under Frick’s direction, what began as a department of one grew into one of higher education’s most effective, envied and emulated fundraising forces. Both a visionary and an organization man, Frick conceived innovative strategies still followed today. He found donors for more than 40 buildings and, at Hesburgh’s urging, mounted the initial effort to ambitiously expand Notre Dame’s endowment. That endowment grew from $9 million to more than $200 million during Frick’s tenure.

Today his blood is in the bricks (as the adage goes), and his legacy abides in the quality and character of the University. Like others who have gone before, his impact outlives his name, although he was an indelible force on all who knew him.

William Sexton, who succeeded Frick in 1983 and served in that vice presidency until his retirement in 2002, said this past April, “Jim Frick was truly the pioneer and mastermind behind Notre Dame’s fundraising success from the very beginning. No one was more creative, more passionate, more energetic, more accepting of sacrifice nor more effective than Jim. He deserves credit for much of the success the University enjoys today.”

I came to work at Notre Dame in late 1977 as a writer in the development office. Even though I was a couple of layers removed from Jim Frick, his presence pervaded the entire division. Frick stories abounded; his pithy quotes — repeated as mantras — became “Frickisms.” His extreme devotion to Notre Dame and his drive and demands for duty and excellence were contagious. He gave his life to Notre Dame, and he spoke eloquently and powerfully about its mission.

His own sense of self-sacrifice and his compulsions — his need for regimentation, punctuality and absolute control — were legendary. It was the first I heard of a “Type A personality”; he met every qualification. Jim Frick, I long ago wrote for a Notre Dame publication, “is a sharp, aggressive dynamo who is fastidiously persistent in his desire for precision and perfection.” He was invariably decisive, assertive, clear and direct. I think we all were at least a little wary around him, yet responded with dedication and loyalty, admiration and affection.

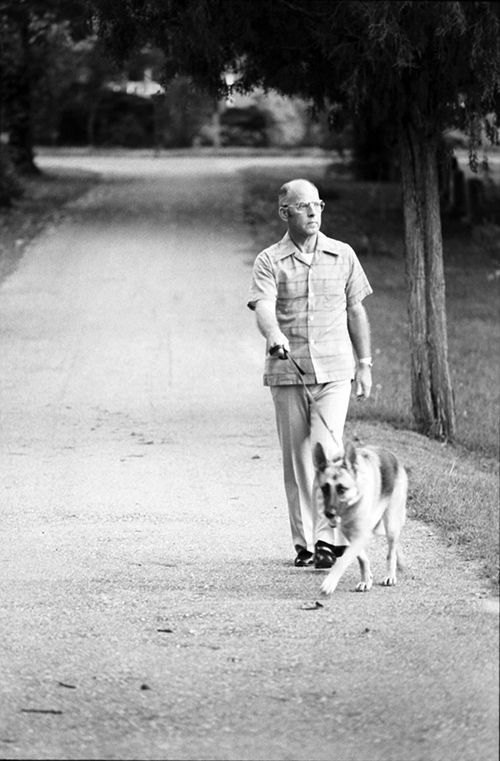

In any given year he could tell you how many days he had spent on the road (214 one year, 252 the next), how many meals he had had at home (102 one year, 182 the next), and that he had traveled 70,000 miles (or some similar figure) on University business over the preceding 12 months. One January night in 1981, I accompanied Frick and his German shepherd, Karla, on their nightly rounds through Cedar Grove Cemetery. It was a cold and memorable night, and I would later recall, “Even this spell of leisure is measured in a typically Frickian way: two steps per second, 360 feet per minute, 10,080 feet in 28 minutes. Nearly two miles in all. And time, solitary time, in which to clear his head, sort things out, think creatively, plan, prepare, analyze.”

His engines, obsessions and devotion to Our Lady’s University exacted a toll on his family and his health. The honorary degree Notre Dame awarded Frick in 1983 (he also earned a doctorate from Notre Dame in 1972) described him as “a man who has literally worked his heart out for Notre Dame.” By his mid-50s, he’d had several heart surgeries (one of the first open-heart procedures performed at Cleveland Clinic) and several heart attacks, two of them nearly fatal. In fact, one day, as the two of us sat is his office, he uncharacteristically strayed from business to talk about his experience floating above his body, looking down, as the doctors, saying they had lost him, scrambled to bring him back — and the great peace he felt while suspended there.

Frick, who always acknowledged how difficult it was to ask others for money, once advised Jim Cooney ’59, who worked under Frick in development before heading the Alumni Association, that when walking through the door for a solicitation, Cooney should pray to the Blessed Mother by saying (as Frick did each time), “This is for you.”

Born August 5, 1924, in New Bern, North Carolina, Jim Frick was the third of five children. His mother died when he was 5 and his father, a victim of the Great Depression, thought he’d be unable to care for his children. He left them at an orphanage run by Catholic nuns, and there Jim stayed through high school, absorbing a deep and lifelong faith as well as a firm belief in order, discipline and perseverance. After a stint in the Navy during World War II, he entered Notre Dame at age 23.

He often told the story of his first rector sending him away from the freshman dorm, declaring him too old and dangerous for the young and impressionable. Another CSC, spying him leaving campus, bags in hand, took him in. Frick always said if that priest hadn’t retrieved him, he would not have made a life at Notre Dame.

Jim Frick was maybe 5-foot-7 (without a pound of bonus weight), but his reach far exceeded his life — not only at Notre Dame but through development professionals who learned from him and then took those lessons to other institutions and through his work for other schools, agencies and organizations. Decades ago he helped launch the Council for the Advancement and Support of Education (CASE), still the leading organization for development, alumni and communications professionals in higher education.

Jim Frick was one of the most compelling speakers I’ve ever heard, an excellent writer, a man with no extraneous words, no time to waste and no appetite for superfluous endeavors, although he loved the arts and music and happily joined a merry band of self-proclaimed “culture vultures” for forays into Chicago or New York for shows, concerts and good meals. Karen Frick, his wife for the final 30 years of his life, knew well his kind, giving and gentle nature, and was largely credited with his longevity and the happy peace he knew throughout his retirement years.

He was preceded in death by his former wife, Bonny, and son Thomas, and survived by children Michael Frick ’74, Terry Frick ’79, Theresa Frick and Katy Meyer, two stepsons, Sean and Daniel Pieri, 13 grandchildren and a great-granddaughter. And an institution he loved and devoted his life to.

Kerry Temple ’74 is editor of this magazine.