A headline in the Baltimore Sun a few days after FBI director James Comey was sacked in May 2017 enjoined that his replacement should have the ethics of Bonaparte. Not the Bonaparte who probably first comes to mind, but Napoleon’s grand-nephew, Notre Dame’s 1903 Laetare medalist Charles Joseph Bonaparte, who was President Theodore Roosevelt’s trust-busting attorney general and the man who in 1908 initiated what became the FBI.

Bonaparte’s foundational role has been obscured in the shadow J. Edgar Hoover casts over the bureau’s history. In his time, Bonaparte’s pioneering crusades against corrupt government, monopolistic big business and bigotry made his establishment of the Justice Department’s “Bureau of Investigation” almost a footnote. Indeed, a laudatory biography published a year after his death in 1921 never even mentions it.

Today an auditorium at FBI headquarters bears Bonaparte’s name, but even many agents are unaware of his other accomplishments. Retired special agent John Quinn ’66 remembers learning about the founder during his training — but that’s about all, he adds.

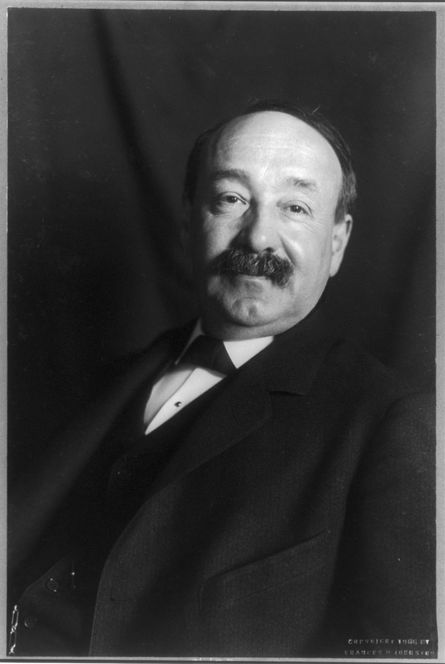

Bonaparte deserves much more space in history books. A newspaper account from his time described him as “too proud to be bossed and too cynical to be fooled. No ‘interest’ or no person does or can control him. He does his own thinking.” The physician, senator and one-time Republican presidential hopeful Joseph Irwin France noted that Bonaparte was “never a partisan, always a patriot.” Furthermore, said France, “although by heredity and his own nature, he was a devout Roman Catholic, there was not in his soul a taint of religious prejudice or intolerance. Jews, negroes, the descendants of all foreign-born were, to him, American equals.”

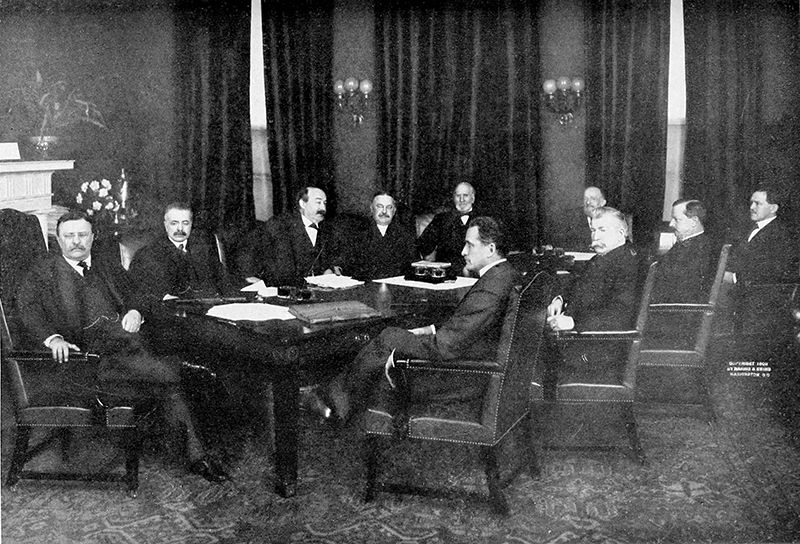

The grandson of Napoleon’s younger brother, Jérôme, and Elizabeth Patterson, the “reigning belle of Baltimore,” — they met at a ball while Jérôme was on an 1803 shore leave from the French navy — the wealthy, blue-blooded Charles Bonaparte was a most unlikely muckraker and civil libertarian. Yet as a reformer and as Roosevelt’s legal muscle he arguably had more impact on the American body politic than any other Roman Catholic layman of the day. “His efforts propelled the policies of President Roosevelt to the end of his administration,” says John Fox ’88, the FBI’s historian, who instructs new agents and other employees on the bureau’s past. “The early 20th century when the FBI was created was a time of great change due to large population increase, rising importance of cities, changing economy from agriculture to technology — and growing need for the federal government to look at matters nationally.”

Bonaparte birthed his fledgling force of 34 special agents on July 26, 1908, without fanfare. He did it deliberately when Congress was on summer recess, end-running the legislative resistance to Roosevelt’s expansion of executive powers and the fears of some lawmakers that TR would establish a federal “secret police” to snoop on them.

In fact, Bonaparte regularly made headlines as a powerful voice for civil-service reform, spearheading Roosevelt’s Progressive agenda and championing the cause of minorities and immigrants ignored or ill-treated by powerful ruling elites. He argued more than 50 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, double the number of any predecessor. He initiated myriad antitrust investigations, including those of Standard Oil, the American Tobacco Company and the Union Pacific Railroad Company.

Bonaparte weaponized his intellect against corruption. “The most forceful mind in the country,” Roosevelt said.

He was often described in such larger-than-life terms, just as his boss in the White House was. Roosevelt was in many ways Bonaparte’s mirror image. Both were Harvard men, although they did not meet at school — Bonaparte was seven years the president’s elder — but rather at a civil-service reform meeting in 1892. Both were Republican-Progressive fire-eaters, unyielding in defense of their principles, and both men had been boxers in their youth.

The state of the nation was as tumultuous then as it is today. Immigration was an inflammatory issue. Unions were organizing and striking. Corrupt urban political machines like New York City’s Tammany Hall lavishly dispensed political patronage. Bonaparte’s native Baltimore was considered the most corrupt city of them all.

By contrast, Bonaparte stood as a pillar of honesty. “He was a Republican but he often voted for Democratic candidates when he thought they were better than the candidates of his own party,” a former law partner wrote. “He was a reformer, but not the objectionable species; he strove for honor in Governmental affairs; he was opposed to ‘bosses’ in either party.” Indeed, some GOP regulars opposed him as much as rival Democrats.

Such opponents, especially among power-brokers and segregationists, were not so admiring. They slurred him for his pro bono services to poor African-Americans in Maryland from the time he started his law practice in 1874. His advocacy for the black community was inspired by his conviction that constitutional guarantees were sacrosanct. To exclude black citizens from the rest of American society “whether by law or natural causes,” he said, “cuts them off at the same time from the only real and certain sense of improvement to themselves,” condemning them to “a life which would remain stationary and outside the fold of American happiness.”

“Mr. Bonaparte accepted literally the faith of the founders of the Republic, that ‘All men are created equal,’” Joseph France wrote. He had “a deep knowledge of our constitution” and was “a most meticulous guardian, lest some profane hand should touch the Ark of the American Covenant.”

Bonaparte was all in for America. He bristled when people implied he was French. He often declared that he had “not a drop of French blood” in his veins, which was true. His original family name, Buonaparte, was Italian. His ancestors had migrated from the Italian mainland to Corsica in the 16th century when that island was part of the Republic of Genoa. The Genoese sold it to France shortly before Napoleon’s birth.

The rest of his lineage would make any American nativist envious. His branch of the Bonapartes apparently had a thing for patrician women. His Scotch-Irish grandmother, Elizabeth Patterson, was the daughter of one of Maryland’s richest men. But her marriage to Jérôme — Bishop John Carroll officiated — was short-lived, annulled by Napoleon after he barred her arrival with warships as the newlyweds tried to reach Europe. The emperor intended to marry his brother off to royalty — and he succeeded.

After the divorce, Elizabeth became a superstar of international society, famed for her striking good looks and plunging necklines that scandalized Americans. She crisscrossed the Atlantic to socialize with the Duke of Wellington, Talleyrand and Dolley Madison. A play and, in the 1920s, two films were made about her.

Bonaparte’s mother, the debutante Susan May Williams, was herself minor nobility and the daughter of a wealthy Scotch-Irish banker and merchant. She gave birth to Charles in 1851.

Despite his bloodlines, Bonaparte empathized with struggling immigrants, especially his fellow Catholics, recognizing that they faced many of the same challenges as black Americans. He was well aware that several Italian immigrants had been lynched in the South during the 1890s. At the same time, he was intent on piloting minorities into mainstream society, pushing them to assimilate. An article in the December 1959 issue of Maryland Historical Magazine describes how he loathed hyphenated ethnicities such as “German-American” or “Negro-American.” Immigrants who cast their lot with America, he declared, must be “not half or three fourths or ninety-nine one-hundredths Americans but Americans altogether, not Americans first and some kinds of foreigners afterwards, but Americans first, last and all the time.”

Bonaparte’s Laetare address reflects how his Catholicism animated his personal life and his views on government and the governed. It was in the Church’s best interests, he said, for Catholics to accept the principle “that no man can be a good Catholic who is not also a good citizen.” As well, he once admonished: “A Christian church cannot escape dealing with evils . . . by closing its eyes to their existence.”

Bonaparte’s biographer, Joseph Bucklin Bishop, said the attorney general’s Catholicism was steeled by the Puritan ethic of his Presbyterian mother and grandmother. He credits them with instilling the ideal that an individual is responsible to society as well as to oneself and the deity and must actively participate in government.

Bonaparte plunged into the reform movement, helping found the National Civil Service Reform League and serving as an early president of what is now the National Civic League. For two decades he led a campaign to dethrone Baltimore’s political machine, which was finally turned out by an election in 1895.

His reform efforts led to his 1902 appointment to the Board of Indian Commissioners by Roosevelt, resulting in revisions of federal tribal policy. TR followed up by appointing him Navy secretary, a staging ground for attorney general when that post opened.

Business interests influenced the press to disparage Bonaparte, but the newspapers soon changed their tune, dubbing him “Charlie the Crook Chaser” for his bulldog pursuit of ill-doers. The crooks he chased were mostly white-collar criminals and civil-rights violators, not yet the bank robbers and mob bosses who were to become FBI targets.

The new attorney general established the embryonic FBI when Congress forbade the Justice Department from borrowing Secret Service detectives from the Treasury Department as temps for its own investigations. John Fox describes how he did it: “He took the handful of civil rights crime investigators, the accountants who looked for fraud in U.S. courts [and] prisons . . . and other white collar crimes, and hired as Department of Justice special agents several detectives previously borrowed from the Secret Service.”

It was a small operation, its agents not authorized to carry firearms. Not until 1935 was the designation “Federal” appended to the Bureau of Investigation.

Despite his role in its formation and the rest of his public accomplishments, the only Bonaparte known to most people is the one who lost the Battle of Waterloo. Yet it is the Bonaparte named Charles who represents what many Americans yearn for today — aspirations he expressed as an undergraduate while envisioning a future that would find “morality and intelligence among the qualities which the American people demand in those who govern them.”

Ed Ricciuti has been reporting and writing for 60 years. He has covered assignments around the globe and has written more than 70 books. When not writing he teaches martial arts near his home in Killingworth, Connecticut.