On a Baghdad roof in the summer heat, small voices of sparrows still chirped amid the gas fumes of generators and the roar of helicopters. A distant bomb shook the air, and smoke rose over Baghdad University. Our landlady sobbed because her son was there taking his final exams. Thank God, he was okay. Later a Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT) colleague and I listened to a man who had been tortured last spring by Iraqi government security forces.

“They used electricity,” he said. “It was so strong that my body was lifted up and thrown down again.”

On another day, we met a soldier sitting atop a tank. This reservist from New York confessed that he was having a hard time. His unit had been fighting Mahdi militias, insurgent groups made up mostly of teenagers, and he could not bear the mismatch of forces that ended in slaughter. “I just wanted to come help poor people,” he said.

Birdsong, bombs, detention, battles, post-traumatic stress disorder—what are we doing in the midst of this chaos?

“What good can you do? What difference does it make? You could do more good in the USA! You should carry weapons, use guards, you should, you should . . ."

The chorus of doubts is powerful. But throughout my two years in Iraq, I have seen the fruits of our pacifist presence blossom, often in unexpected and humbling ways. What are we doing there? We are trying to follow Jesus’ example of nonviolent, active love by taking risks for peace, just as soldiers take risks for war.

CPT is an ecumenical organization that sends invited teams of trained peacemakers to work with local partners in areas of armed conflict around the world. We live in ordinary neighborhoods and work with local peacemakers. In Iraq, we help train Iraqi Muslim Peacemaker Teams, document human rights abuses, accompany detainees’ families and others who live in fear, and tell our home countries about the realities of war and occupation.

Above all, we are in Iraq to be present and to listen. One Iraqi friend said simply, “You are together with us in our suffering.” Saint Catherine of Siena, a contemplative activist of her own day, says, “Look within and see that you are loved . . . and you will be able to do nothing except love.” The purpose of all our work in Iraq is to help us all see who we really are—brothers and sisters of one family.

February 2004:

Yesterday I sat on a pile of rocks outside Ramadi with a young Iraqi woman whose brother died in a house raid. Four U.S. soldiers were killed in “friendly fire” that night. They thought they were being fired on by Iraqis and ended up killing each other. When the survivors realized what they had done, they were so distraught that they executed their three Iraqi prisoners, then demolished the house.

The young woman wailed, “Why did they do this?” Somewhere, U.S. families also weep. I wish they could meet and dry each others’ tears.

March 2004:

The other day my little neighbors and I played a game of soccer on the roof. Mohammed kept losing his sandals and slipping on the tile, and the ball nearly overturned boxes of vegetables and pails of whitewash. Seven-year-old Noor was like an angel of destruction unleashed! It was great fun.

July 2004:

I was so frightened today, afraid to take a journey on a dangerous highway. But in the end I met one of the most beautiful people in all Iraq. Mr. Najib is a frail 59 years old. Last year U.S. soldiers detained him and sexually abused him. But in prison he found both a second son and forgiveness for his captors.

“There was a doctor there, a soldier from the U.S. He was so noble and kind. He hugged me, crying so much that his tears fell on my cheek. When I saw him, I saw my son. Some of the soldiers were harsh, but Dr. Jasy treated me with kindness. He called me ‘Baba (Father) Najib.’ One day he came in singing, ‘Happy Biiiirthday Baba Najib! You’re gooooing home!’ I was released."

November 2004:

Margaret Hassan, an aid worker, has been killed. Tom Fox, Matthew Chandler and I talk about whether we should stay. Tom is like an anchor. I feel surrounded by fears.

But we are also surrounded by friends. Our Muslim neighbor Abu Ali insists on driving us to church even though it is only a few blocks away. A shopkeeper tells me, “If anyone tries to hurt you, I will protect you.” Another neighbor says, “Come to my house anytime, even in the middle of the night."

April 2005:

This morning I woke up to the ringing phone. It was Abu Zayneb, a founder of Muslim Peacemaker Teams (MPT). “I am calling to offer condolences on the death of the pope,” he said. “He was a good man who tried to bring peace to all the world."

May 2005:

We have been so busy. Lately we’ve hosted two house guests and more than 20 visitors; heard five testimonies of detention and torture; witnessed a car bomb; referred two children who need out-of-country medical treatment; planned a trip to Fallujah with MPT; attended a demonstration for detainee rights; met with a sheikh, a union organizer, the director of MPT, two Iraqi human-rights groups, two Iraqi journalists, a Chaldean priest, neighborhood friends and a women’s-rights organizer from Najaf.

But what difference does it make? The violence still spins out of control, ethnic tensions are exploding, people are tortured and suicide bombs are detonated every day, lines for gasoline stretch for miles, reconstruction has stalled, there’s no electricity and not enough fuel.

Kidnaping crisis

Last November, two days after I left Baghdad, four of my CPT friends disappeared. Jim Loney, Harmeet Sooden and Norman Kemper were rescued by Coalition forces in late March. Tom Fox, whom I knew and loved, was killed by his captors.

Did Tom’s presence in Iraq make any difference? Last fall, Tom and I accompanied five families fleeing threats of torture in Baghdad, then lived in tents with them for two weeks in the Syrian desert. Those refugee children will never forget the gentle giant who gave piggyback rides. They wept when they learned of his death. Does it make a difference, to be precious to a child?

In the midst of the kidnaping crisis, the CPT team in Baghdad was visited by a dignified Iraqi gentleman. He introduced himself as a member of the “Independent Activates,” a new Iraqi human-rights group. Sunni and Shi’ite united, they had organized several public demonstrations, begging for the release of the CPT hostages. “You have many friends in Iraq,” he said.

Muslim leaders all over the world spoke out on behalf of CPT. Some traveled to Baghdad, risking their own lives to save ours. As a result, millions of Muslims now know that some Christians risk their lives, without using guns, for peace in the Middle East. Millions of Christians know that their Muslim brothers and sisters took great risks to help CPT in our time of great need.

When Tom died, Sunni, Shi’ite, Kurdish and Christian Iraqis gathered for a memorial service in Baghdad. They read from the Gospel and the Qur’an, listened to Tom’s own writings and remembered the man they loved as their own. Tom brought people together, even in death.

When Archbishop Desmond Tutu spoke at Notre Dame on September 11, 2003, he said, “True peace and real security will never come from the barrel of a gun. They will come when we act from the perspective that people matter."

Tom’s life and CPT’s work is about living as if people matter—even those people who, forgetting their own humanity, commit heinous acts of violence. How can we awaken to this reality, to our deepest identity? By deciding that violence is not an option, crossing borders of fear and taking risks.

Two years ago, car bombs ripped through the city of Karbala. Little Noor, my beloved 7-year-old neighbor who loves soccer, singing and crayons, was there with her family at a religious festival. When at last I saw her, safe and sound, I burst into tears. That is when I realized how much I loved her. She walked me back to the apartment hand-in-hand, ducking into a store at one point and emerging to press a single bubble-gum ball into my hand before scampering back home.

How would global relationships and methods of conflict resolution change if we all felt that each child was as precious as Noor is to me? If we knew that each child is our own daughter or son, each elder is our beloved parent, each person—insurgent, soldier or pacifist—is our own brother or sister? It could make all the difference in the world.

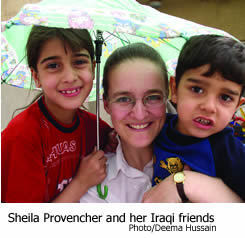

Sheila Provencher lived and worked with Christian Peacemaker Teams in Baghdad from December 2003 to December 2005. She continues to serve as a CPT reservist while pursuing premedical studies in the Boston area.