“Some days it was routine. Other days I would sit at the microfilm reader and weep,” says William Cavanaugh ’84.

In those early spring days of 1990, Cavanaugh had just returned from serving as a Holy Cross Associate in Chile and was preparing to begin his doctoral studies in theology. He was asked by Father Bill Lewers, CSC, then the director of Notre Dame’s Center for Civil and Human Rights, and Father Tim Scully, CSC, ’76, ’79M.Div., to assist with a new project.

He would help the human rights center index 84 microfilm rolls containing hundreds of thousands of pages that documented the horrific human rights violations committed by Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet.

“Eight hours a day, I would read accounts of torture,” says Cavanaugh. “I remember having nightmares, maybe two times a week.” His years in Chile had left him intimately familiar with the impact of these crimes on mothers and fathers, daughters and sons. His next-door neighbor had been picked up by security forces and was never seen again. He simply disappeared. And he left behind a wife and a 1-year-old son.

It was the Vicaría de la Solidaridad, a human rights office set up by Cardinal Raúl Silva soon after Pinochet’s violent 1973 coup, that kept the records of the regime’s human rights abuse — ultimately more than 30,000 cases of disappearances, killings and torture. In meeting after meeting with the bereaved family members who would line the halls of their offices attached to the Cathedral in Santiago, the Vicaría’s meticulous documentation program helped to ensure that the wronged would not also be the forgotten.

- Chile's Long Darkness

- La Cueca Sola

- The Rest of the Story

Through an agreement between the Vicaría and the order of Holy Cross, those documents were microfilmed and smuggled by Father Lewers to South Bend for safekeeping.

When the Pinochet dictatorship ended unexpectedly in a 1988 referendum, the Vicaría’s original files became the lifeblood of the new president Patricio Aylwin’s National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation.

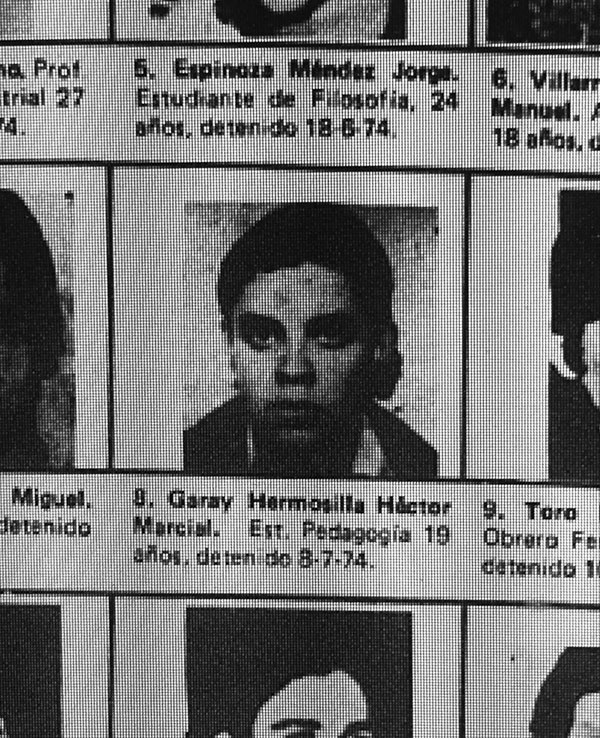

The truth commission’s 1991 report includes details surrounding the disappearance of the young man written about by Nathan Stone ’79 in the accompanying article: Héctor Marcial Garay Hermosilla, nicknamed Tito, was arrested by “unidentified agents” at his home on July 8, 1974, in the Ñuñoa district of Santiago, the home of the National Stadium infamously converted to a detention and torture center. The commission deemed Tito to be a victim of “human rights violations committed by government agents.”

President Aylwin sought to share the Chilean experience as a model for other societies making the painful transition from dictatorship to democracy. Given Notre Dame’s role in safekeeping the files of the Vicaría, Aylwin turned to the University’s Center for Civil and Human Rights to publish the truth commission report’s official English translation. The center’s translation helped to launch the academic field of transitional justice — how societies establish truth, justice, reparations and guarantees of no repetition after periods of gross human rights violations.

Notre Dame’s center also contributed directly to other efforts at reconciliation around the globe. In 1994, the center’s associate director, Garth Meintjes ’91LL.M., ’05JSD, sent Notre Dame student Judith Robb Cohen ’95LL.M. to hand-deliver a copy of the center’s translated report to the South African Minister of Justice, Dullah Omar. The minister used the report of the Chilean experience to help shape South Africa’s post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission, chaired by Bishop Desmond Tutu.

In 2004, the center joined the Institute for Democracy and Human Rights at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru to publish an English translation of Peru’s influential truth commission report.

Ten years later, the University’s human rights center joined the New York City-based International Center for Transitional Justice to launch a graphic-enriched online version of the Peruvian report’s translation, making it accessible to scholars and practitioners worldwide.

And since its founding by Father Lewers in 1988, Notre Dame Law School’s master of laws (LL.M.) program in international human rights law has enabled more than 400 lawyers from over 100 countries to study the transitional justice efforts of Chile, South Africa, Peru and other nations seeking accountability and reconciliation.

Recently, Notre Dame’s copy of the Vicaría’s archives provided an additional link to Nathan Stone’s story of a distraught mother seeking her disappeared son.

Decades on, high up in the Hesburgh Library, nestled behind the Word of Life mosaic, the archive of the Vicaría and the testimony of Inelia, the anguished mother of Tito, continue to speak truth to power. Wound deeply into microfilm roll number 8 is document #8389, a letter sent by Inelia and la Agrupación, Families of the Disappeared, to Manuel Contreras, head of Chile’s secret police. The heartbroken relatives accuse him of complicity in the disappearance of Tito and “the 119,” young Chileans the Pinochet regime insisted had not disappeared but had fled the country. The next document includes Tito’s black-and-white school photo, lovingly placed in the archive in the hope that justice would one day prevail.

In 2015, Contreras died in prison, sentenced to more than 500 years for his crimes against humanity.

Sean O’Brien is assistant director of Notre Dame’s Center for Civil and Human Rights and a concurrent assistant professor of law.