Knute Rockne reached the height of his success and fame in an era when sports reporters saw, in four 158-pound backs winning a game 13-7, all the horsepower of the apocalypse. As the creator of this force of nature, Rockne ascended to godlike status among the writers who chronicled, and fans who celebrated, Notre Dame’s phenomenal 1920s football teams.

The coach’s death in 1931, while still in his championship prime, polished to a high gloss the legend that Grantland Rice and his ilk erected in his lifetime. Then Rockne’s wife, Bonnie, and University administrators bronzed it for generations with their meticulous control over the 1940 movie, Knute Rockne All American, which bears only a passing resemblance to reality.

For the average person, there was no way of knowing the real Rockne. At least not until the early 1990s, when historian Murray Sperber unearthed him in a sub-basement of the Hesburgh Library. Inside unexamined boxes were 25 years of athletic department records, including 14,500 letters and memos between Rockne and the Notre Dame hierarchy, fellow coaches, reporters, business partners and boosters. The epistles were illuminating.

“Reading them,” Sperber writes, “was like entering a world that I hardly knew existed — one so contrary to the legends and books about American college sports and Knute Rockne that I was startled by the discrepancy between the myths and the actual historical records in my hands.”

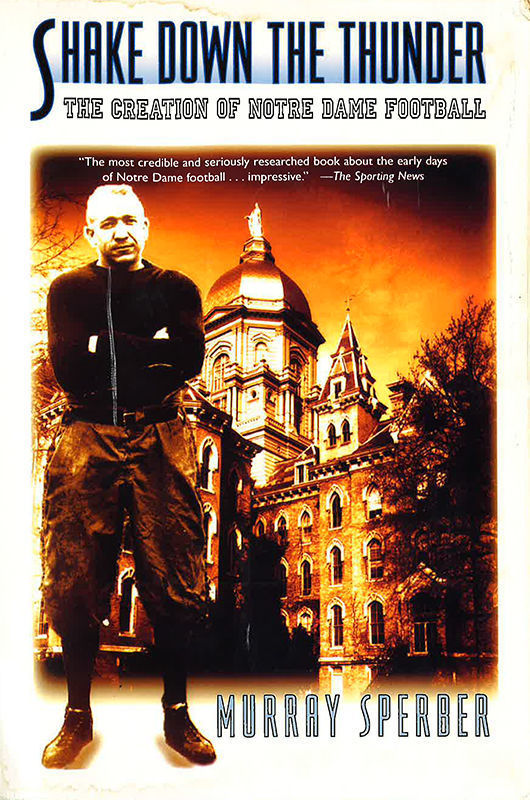

I read Sperber’s 1993 book, Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football, long ago and picked it up again this summer in preparation for teaching a class on sports journalism. (Many of that industry’s most famous practitioners don’t hold up well under historical scrutiny either.) The Rockne who emerges in Sperber’s telling is no St. Knute but is all the more interesting when possessed of recognizably human characteristics like ambition and cunning. Rockne was innovative and pragmatic in football and in business, a pioneer in extreme coaching perfectionism and in lucrative side hustles.

Those are the reasons we remember him, even if that’s not the Rockne we remember. In our collective memory, the erstwhile chemist applied his intellect to football instead, stirring scholar-athletes to victory with tactical acumen and motivational panache. There’s some truth to that. Ish.

Rockne, who enrolled at a very different Notre Dame in 1909 without a high school diploma, came for an athletic culture that valued physical toughness as the core characteristic of masculinity and the American way. He never shed that attitude. As a coach, he proclaimed that football instills “in the average man more of the ingredients of success in life than almost any academic course he takes.”

He didn’t try to pretend otherwise — those were public comments; like others they lamented a feminizing intellectual culture encroaching on campus — but Rockne does bear some responsibility for posterity’s mistaken impression of him as a virtuous proponent of the amateur ideal. It’s not all the fault of movie stars Pat O’Brien and Ronald Reagan. Rockne’s autobiography, collected from ghostwritten articles published in Collier’s, misrepresents his views on various subjects.

“The faculty must run the institution,” the ersatz Rockne wrote during a time when cries of “overemphasis” dogged college football. “The school is their school, and the coach must bear in mind that his is an extra-curricular activity like glee clubs, debating societies, campus publications and so forth.”

The real Rockne, as the remarks Sperber documents make clear, didn’t believe that. And despite these words appearing under his byline, he also didn’t believe that “the coach who goes around trying to fix it for athletes to be scholastically eligible when mentally they’re not, is a plain, every day fool.” Unless he was calling himself a fool.

“In fact,” Sperber writes, “Rockne fought to keep many of his starters scholastically eligible, and only the vigilance of the C.S.C. priests and lay faculty and their obstinate desire to make Notre Dame a serious academic institution kept him in check.”

Championships, and the power and popularity that came with them, made Rockne difficult for his bosses to control, but University leaders like President Rev. Charles L. O’Donnell, CSC, won in the long run. Rockne’s misleading words, far more than his deeds, became the Notre Dame football operating manual — the administration and the academy know best, defer to them and win ’em all with only the best and the brightest. “Held up as scripture to subsequent Fighting Irish coaches, his successors could not violate the master’s creed,” Sperber writes, “even though the great man had neither written the words nor lived by them.”

The Rockne of Shake Down the Thunder differs in other ways from the traditions attributed to him. For example, in his “scheduling technique of opening the season with two easy home games,” in his leveraging of coaching offers from Columbia to USC, and in the accommodations he made in order to moonlight.

He missed the 1926 Carnegie Tech game, which Notre Dame lost in an upset, to make an appearance promoting his syndicated newspaper column. And he ceded the entire 1929 spring practice to his assistants because an endorsement deal with Studebaker required him to be on the road.

That’s not to say he wasn’t obsessed with winning, demonstrating an “insatiable perfectionism” that included coaching at serious risk to his health when doctor’s orders counseled rest. And he would stockpile many more recruits than could ever play a varsity down, a tactic of keep-away from the competition. Even the protégé who may have admired him most, Frank Leahy, considered Rockne’s squirreling away of so much talent a “sinful . . . squandering of humanity.”

If this process of setting the record straight sounds like a takedown, it’s not. Sperber reiterates often that Rockne operated within the norms of his times. Notre Dame’s rivals often come off worse from scrutiny of their hypocritical sanctimony. And Sperber offers a magnanimous reading of Rockne’s leniency to players who flouted academic or athletic rules as evidence of his loyalty, rather than mere mercenary expediency — although there was that, too.

Sperber presents a man in full, and in context, no more implicated in the corrupt practices of the era than his peers (and probably a little less, thanks to his superiors). A Rockne calculating in the cultivation of sympathetic reporters, aggressive in the pursuit of personal financial gain, creative and deceptive in maneuvering around and through opponents and rulebooks.

And, for all those reasons that belie the “innocent and idealistic” caricature of prior biographers, a Rockne successful beyond measure in his own time and ever since.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.