I call it notwriting. All one word. Not to be confused with not writing. A space in between means I just happen to be doing something else, otherwise engaged, off the clock. Run together, notwriting represents a conscious act of avoidance, a calculated diversion, a dodge. Anything but writing.

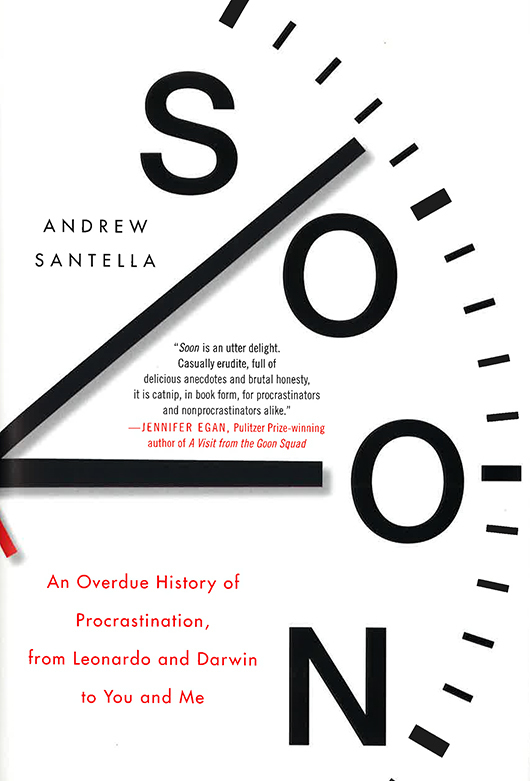

There’s already a word for this shirking behavior, of course. A term not limited to precious writers, or even to occupational obligations in general. An expression of the human inclination to put off whatever must be done: procrastination. Andrew Santella has written the book on it. Soon, it’s called.

Santella’s credentials, it should be noted, call into question his expertise on this subject. He’s a frequent contributor to this magazine, his essays submitted on time (or what passes for it in our world), fine-tuned to an easy readability possible only through dedicated attention to detail. Now along comes Soon, exhibiting the same evidence of hard work, all of which makes him seem pretty effortish and more than a little finishy for a guy purporting book-length insight into putting stuff off.

I mean, it took me longer than strictly reasonable just to read the thing — no slight to Santella, just a symptom of the syndrome his book diagnoses. It wasn’t even an assignment. I’m a fan of his writing, so I volunteered, but at that moment it became work and subject to all my recurring psychological stall tactics.

To say nothing of the sand dunes that passed through the hourglass before I mustered even 250 words of this glorified jacket blurb that I’ve been slogging through since. . . . Look, let’s not make this a competition about who’s the biggest procrastinator, as pleasantly distracting as that might be from more pressing responsibilities.

In his defense, Santella has been at this for a while. He first wrote about procrastination for us in 2014, a pretty long time ago for a precursor to a book that just came out this year. Soon is subtitled An Overdue History of Procrastination, From Leonardo and Darwin to You and Me. I’m glad he finally got around to it.

If you think the You in the subtitle might refer to you, personally, Soon will confirm that impression. It’s a book that inspires a lot of solidarity nodding.

Santella experienced the sensation as he immersed himself in the psychological research on procrastination. All the paradoxical, contradictory reasons people engage in such self-defeating behavior were states of mind he recognized in himself.

Perfectionism that makes it seem impossible to meet high personal standards and, therefore, futile even to attempt? Check. Such certainty of failure that not doing the work in the first place provides a preemptive excuse? That too. Relishing the adrenaline rush of a last-minute sprint to a project’s finish? Guilty. Paralysis from the sheer amount of work to do? Yep.

It’s not that procrastinators never get anything done; it’s that, for all the reasons above and more, getting things done is a dead-weight drag, circled with dread like a suspicious package, false-started and stopped at the faintest strain of effort, with progress incremental to the point of being invisible, an exhausting act of resistance against a wandering mind’s greedy susceptibility to distraction.

Folding laundry is a relief by comparison. Twitter is an outright treat. “If we have to,” Santella writes of his compatriots in procrastination, “we’ll even work out.” So you can see the insidious lure of notwriting — or notstudying, or notlawnmowing, or notwhatever is next on the to-do list.

For those who are not afflicted with the curse of procrastination, it’s easy to confuse with laziness. Procrastination and laziness both involve a lot of gratuitous napping, for example. But there are differences. Among them: procrastinators often accomplish a lot, just not their immediate mandate. As the humorist Robert Benchley put it, “Anyone can do any amount of work, provided it isn’t the work he is supposed to be doing at that moment.”

Santella sums up the psychological consensus on procrastination as “postponement undertaken despite expecting to be worse off for the delay.” We know, we know. And yet.

Side effects include guilt about our failure and brooding over all that has been left undone in the accumulation of hour after unproductive hour. “I’m always doing a kind of existential calculation,” Santella writes, “weighing what I do against what I might have done, or against what I have not yet done.”

Shadowing all of this is the unknowable but ever-shrinking variable of exactly how much time we have left. Like, on Earth. The phrase “killing time” takes on particular poignancy in this context.

Not that consciousness of life’s ultimate hard deadline inspires Santella to feats of efficiency. He takes no pride in his delaying tendencies, but to a certain degree, he embraces them as a rejection of a human life reduced to a body of work.

Too often, he argues, personal growth is measured within the narrow confines of professional proficiency: “Productivity is operative gospel; to be a fully successful human it is necessary to get things done.”

So he’s not about to repent at the altar of productivity. Soon isn’t a self-help book. “My aim wasn’t to end my habit but to justify it,” Santella writes, and he marshals an all-star team to help quiet the voices in his head urging him to get on with it.

There’s St. Augustine — “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet” — along with Leonardo da Vinci and Charles Darwin. Twenty-five years passed between Leonardo accepting a commission from Milan’s Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and the installation of his painting of Mary and Jesus. He had committed to completing it in seven months.

That’s not quite the whole the story of the two — let’s call them drafts — of The Virgin of the Rocks. Santella explains the exculpatory context, but Leonardo did drag out the process, true to his contemporary reputation for frustrating patrons with his dallying. Apparently Pope Leo X said, “This man will accomplish nothing.”

Leonardo would agree to paint portraits for important people, then distract himself with flights of his fertile mind, such as, “describe what sneezing is.” This annoyed the important people, but Santella interprets the digressions as the necessarily winding, diversionary path of a polymathic genius: “Isn’t it possible that a more workmanlike Leonardo, one who cared only about pleasing his patrons and meeting deadlines, would have done nothing worth remembering?” This is how we procrastinators comfort ourselves when we should be working.

Darwin was all about barnacles. He let the scientific insight that would immortalize him languish for two decades while he labored over barnacles. Lots of other stuff, too, all trivial compared to his theory of evolution, but the study of barnacles was so consuming that one of Darwin’s children asked, while visiting a friend’s house, “where does your father do his barnacles?”

Perhaps the immense scientific, religious and cultural implications of natural selection waylaid him? Or maybe he never felt certain enough in his conclusions to suit his perfectionist taste? It couldn’t be that he just cared more about barnacles. Darwin never explained the diversion, although about the barnacles he did acknowledge, “I doubt whether the work was worth the consumption of so much time.”

In that way — and pretty much only that way — the everyday procrastinator can claim kinship with Darwin. “He reminds us of the knottiness of human motivations,” Santella writes. “We all have our lists of things we should do, things we must do. And yet we find some reason not to do them.”

Reading Soon is as good a reason as any.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.