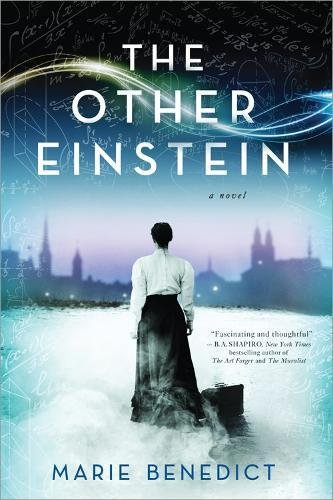

Watching National Geographic’s period drama, Genius, which in its first season told the story of Albert Einstein, held a fascinating surprise for me: his first wife, Mileva Maric. She, too, was a talented physicist. So when I came across a historical novel about her, The Other Einstein by Marie Benedict, I jumped on the opportunity to learn more.

Halfway through the book, though, I began to feel uneasy. By the end, I was in an all-out battle with the boundaries of truth-stretching. In part, the difficulty is a reflection of my struggle with today’s political climate. Truth has always been a tenuous commodity in politics, but its value currently seems to be at an all-time low. Fortunately, one of literature’s great perks is that it enables me to grapple with hard issues in a less stressful setting than politics.

First, the premise:

The Other Einstein, a story told through letters, begins as Maric travels from her home in Serbia to study at the university in Zurich, Switzerland, where she soon meets fellow physics student Einstein. They fall in love and have an affair; she gets pregnant, flunks her exams — twice — and never completes her doctoral degree. Eventually Einstein and Maric get married and raise two sons while reshaping the entire field of physics — and drifting apart. The novel ends with the couple’s divorce.

Some of Maric’s struggles are ones I’ve experienced firsthand. I completed my Ph.D., albeit in political science, and during the year I finished and defended my thesis, I had my first child, albeit while married — but after being warned by a male member of my dissertation committee not to get pregnant. Maric’s story resonated on so many levels. I wanted to know all of it.

However, many of the facts about her life are lost in the folds of history. Researchers aren’t sure what happened to the couple’s first child — a daughter named Lieserl, who disappears from the records within two years of her birth. We also don’t know what role Maric played in Einstein’s academic work. Some biographers posit she was at least a collaborator; others suggest she was the mathematical brains behind his theories, including the theory of special relativity.

Think about that for a moment. Einstein is credited with the first coherent explanation of how, in the words of science writer Elizabeth Howell, “space and time are linked for objects moving at a constant speed in a straight line”; how, as an object approaches the speed of light its mass becomes infinite and is unable to surpass light.

This is mind-bending stuff. Einstein’s theory revolutionized physics.

In The Other Einstein, the couple collaborate, but the idea is Maric’s. However, because Einstein has the academic title and Maric doesn’t, he takes the credit for the work, including — in 1921 — the resulting Nobel Prize in Physics. Maric gets nothing.

Benedict states in her afterword that there is no proof Maric played any role in Einstein’s research, but that as a novelist she chose to take the imaginable to its limits, suggesting Einstein stole Maric’s ideas. It’s a hefty fabrication that left me struggling with a host of questions:

1. Is the fabrication really necessary? Maric’s story is already fraught with all sorts of disaster. For example, the real Einstein was unfaithful. When the marriage was in dire straits, he created a cruel list of demands that would have turned Maric into his servant, and then he divorced her to marry his cousin. Some researchers claim to have police reports showing he beat Maric (a facet Benedict includes in her story).

It’s a bona fide, juicy non-fiction scandal. But by taking it one step beyond established facts, Benedict’s Einstein goes from mere louse to predatory thief.

2. What effect does the fabrication have on popular grasp of facts? The Other Einstein may be the only thing many people will read about Mileva Maric, and it skews what we do know, badly.

Some may argue this is not a big deal. After all, this is historical fiction, not politics. Yet, if we tolerate bastardized facts here, why not there? Scott Adams, the creator of Dilbert, described in a recent Wall Street Journal commentary how President Trump’s truth-stretching tweets “make us think past the sale”: Without even realizing it, we take whatever he says as fact because we are already wondering about the consequences.

For example, Adams writes, “When Candidate Trump said he would make Mexico pay for the wall, he was making us think past the sale. If you’re thinking about who is paying for the wall, you’ve already imagined the wall existing. And that makes it easier to convince you it should exist.”

I’ve imagined an Albert Einstein who stole one of science’s greatest achievements. It’s an unsettling possibility. Unsettling possibilities may inspire us to do great things, such as rectify past wrongs. When they don’t reflect truth, however, they can also cause great harm. Much like an accused person who is ultimately acquitted, the tarnish of the accusation never quite goes away. It haunts the person.

3. What responsibility do we have to truth? Truthfulness is a nearly impossible ideal to live up to. We’ve almost all told a white lie or two. But most of us set boundaries. As an academic, if I made my data lie, I’d have lost my credibility as a researcher. As a writer, I’d argue it’s not much different.

Yet we tolerate a lot of truth-stretching these days. Can we blame a writer who takes that tolerance and runs with it? Is that kind of free-play with facts a symptom or a cause of our larger problems with truth? Does it really matter?

The fact that we’re seeing such truth-stretching far and wide presents an opportunity to amend the trend, to choose truth-telling, not truth-stretching. Truth, it is said, is stranger than fiction. Imagine the places we could go.

Stacy Nyikos is the author of many award-winning books for children. She is currently working on a young adult science fiction novel that is a loose retelling of the story of Moses set on a drowning planet. For more information about the author and her books, visit her website.