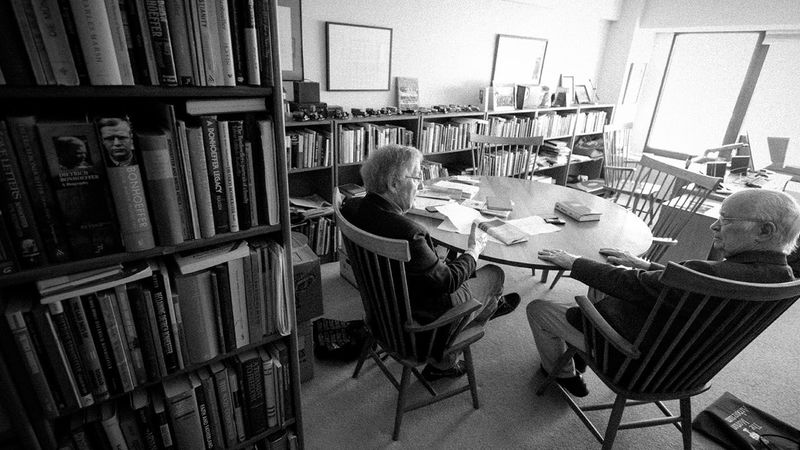

Ken Woodward ’57 was religion editor at Newsweek for 38 years, retiring in 2002. He is the author of several books, including most recently Getting Religion: Faith, Culture, and Politics from the Age of Eisenhower to the Era of Obama. Martin Marty — as a former Lutheran pastor and author, essayist, book editor and professor at the University of Chicago Divinity School — has for decades been the nation’s prominent authority on the role of religion in U.S. history and culture. We asked the two friends if we could eavesdrop on one of their conversations. What follows is an abridged transcript of a conversation that took place in April 2017, a few days after Easter, at Marty’s residence on the 59th floor of the John Hancock Center in Chicago.

Ken Woodward: In the opening chapters of Getting Religion, I describe how healthy and pervasive religious belief, behavior and belonging were in the United States in the 1950s. When asked, 98 percent told pollsters that they believed in God, and membership and attendance at worship services were high — higher than any time before or since. We built more churches and synagogues than at any other time. Catholic seminaries were booming, as were the orders of nuns. Protestant seminaries could pick and choose among candidates who might otherwise become doctors or lawyers or corporate executives. They got an elite crowd, by and large.

By 1960, half of all school-aged Catholic children were enrolled in parochial schools. Moreover, American culture supported religion, in large part because we had a war with atheist communism. Recall, it was in the ’50s that we put “In God We Trust” on our currency and added “Under God” to the pledge of allegiance. And it was in the 1950s that the Republican National Committee declared that President Eisenhower was not only the nation’s commander-in-chief, but also — this is a quote — “The spiritual leader of our country.” And at Notre Dame this fusion of faith and culture and politics could be seen chiseled in stone, “For God, Country, Notre Dame.”

So here’s my question: Are we, you and I, people like us, who came of age in the ’50s, right to see the end of the 20th century as marking a devolution in religious belief, behavior and belonging? At least of the kind that was available in the ’50s? Or should we bracket our personal experience of 1950s religion as an aberrant high-water mark, against which to measure subsequent generations?

Martin E. Marty: I think we would have a different view if we were formed in the 1920s, which was kind of a low period. By the time of the Depression it was really low. When I wrote about this period, I looked for any place that anybody in the ’30s said, “There will be a revival of religion coming.” Then came the war. There was one book by Henry Link called Return To Religion or something like that. But it was an advice book. Like you should get it, not that he could see it. And no statistics would support anything big going on.

So if you’re measuring from that — war time, GIs coming home, people wanting to settle down, then yes, you’re right, a cultural mood shift. I like to quote Ortega y Gasset, “Real history is not made so much by who wins a war, or famine, or an earthquake, real history is made when,” I love this phrase, “the sensitive crown of the human heart tilts ever so slightly from optimism to pessimism or from despair to hope.” And I think it was that tilt which showed up.

Today’s New York Times has a big graph of how popular presidents were after one month. Eisenhower, 75 percent, and right down the list, losing about 3 or 4 percentage points every time. And now we’re down to 40 percent. Obama was not much higher. The high points signified a great deal of cohesion, coherence, consensus, and there’s no doubt we’ve lost that. You and I, we will look at and see this drastically, my college-age grandchildren didn’t ever see that, so they’re not surprised.

Yet when I read about the mainline churches being in trouble, I think, well, my son, a minister in Davenport, called here last night and just beaming — “Oh, we’ve never had an Easter crowd like we had this year.” And at Easter dinner with a friend, who’s a pastor there, said, “Man, we had three services and you couldn’t fit people in.” So you have all of these slices where you have things going on.

But overall, Catholic and Protestant seminaries are down and having a harder time getting quality candidates.

KW: What I find interesting is that if the mainline churches hadn’t decided to ordain women, some of those places would be closed.

MM: Oh, yeah. Half the seminarians and many of the best pastors are women. Well, Thursday night you heard one, and she was on top of things, had things to say. That’s technically an evangelical church, but it’s mainline in ethos.

KW: When I look at it, my norm is different because of what I knew when I was a kid. But if you were born since then, if you were born in the ’60s, ’70s, you’d have a very different view.

MM: But it isn’t just the statistics, cultural norms have changed. So everyone we know says, “Oh, our kids in college have no idea why Catholics and Protestants are so concerned about LGBT and so on.”

KW: Yeah.

MM: So they don’t get it. Why have big fights about gay marriage and all that? There’s a cultural norm shift. And that one I don’t think was because of argument, I think it was experience. You’re anti-homosexual and you don’t want your church to recognize them, and then your niece comes along, and she’s your favorite, and she comes out. What are you going to do about it?

KW: Yeah, but also, Marty, I watch my children and my grandchildren and there’s an ethic of nonjudgmentalism. If you don’t judge me, I’m not going to judge you. Which it seems, you’ve got an upside and a downside.

There’s a sense in which you don’t want to be seen as judgmental. If someone were to say, “Look, some think there is something unnatural about whatever it is you’re talking about, but I don’t.” I welcome the lift of opprobrium, but I get a little nervous about that.

Martin Marty, photography by John Zich

Martin Marty, photography by John Zich

Woodward: Getting people interested in the past is a problem. But in terms of religious energy and innovation, the second half of the 20th century is a match for the second great awakening that erupted a century earlier. Antebellum America. Back then, we saw the emergence of the Disciples of Christ. Mormons, I think. Adventism goes back to that, and the flirtation with Asian spirituality via the transcendentalists — Hindu and Buddhist gurus, and their spirituality also figured in what I call the experiential religion of the 1960s and ’70s, coming out of the counterculture. When young people wanted almost any religion but that of their parents. But only so long as they get to experience a spiritual high or transformation. They weren’t much into doctrine.

Now do you, as the author of a three-volume history of modern American religion, think that the comparison is apt? Because I saw a paradox there. On the one hand, you saw a decline of ’50s religion, mostly Christian. To some extent Jewish. And at the same time, all of these religious energies going in other directions like a sunburst.

Marty All of the people in my business quote G.K. Chesterton, “When people stop believing in God they don’t believe in nothing, they believe in anything and everything.” And it’s that kind of explosion, with a very private trajectory, and tomorrow could be something different.

KW: The 1950s was also the time of the coming into prominence of what I call “entrepreneurial religion,” by which I mean Billy Graham, Bill Bright, all of these people.

MM: Fulton Sheen.

KW: And Fulton Sheen. It wasn’t just a matter of people going to church. Religion was very much in the public eye. You read it on the pages of Newsweek and Time, and the newspapers, and you heard it on the radio. It was a time where religious leaders, religious institutions, the National Council of Churches made pronouncements and people paid attention to that.

There were religious thinkers, ideas and movements. Very prominent in the public square. When the pope spoke to Congress a couple of years ago, he cited Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. All came from the era.

Well, here’s my list. Martin Luther King, Billy Graham, Bishop Fulton Sheen, Jerry Falwell, the Berrigan brothers, no order here: Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, Reinhold Niebuhr, Paul Tillich, both on the cover of Time; John Courtney Murray, another Time cover, Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, Bishop James A. Pike, on the cover of everything but Time. Cardinal Bernardin, late in the game. Father Hesburgh, the Dalai Lama, writers like Flannery O’Connor, J.F. Powers, Walker Percy, T.S. Eliot, with his long shadow over the domain of letters, W.H. Auden. Think, too, of secular theology, liberation theology, black theology, feminist theology, televangelism, transcendental meditation, the God is Dead movement.

Now some of these were flashes in the pan, but they were in the public discourse and people paid attention — even those who probably weren’t religious. A lot of these figures and movements emerged in connection with the social and political turbulence of the era.

But in the epilogue of my book, I note that for the first 17 years of this century what’s gone on has been every bit as volatile. In that time, America has experienced 9/11. A terrorist attack on American soil, the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression. The longest period of being at war in our history, and most recently the political upheaval created by the political campaign and election of Donald Trump. Yet throughout all of these events, there have been no religious figures, no religious movements or ideas that I’ve been able to notice, in response to these things. Once again it seems religion is absent from the public square.

Why? Or am I wrong?

MM: I think there’s still another shift happening. I call it “religio hyphen secular.” Religio-secular. I think what’s happening is that everything you pulled out and called religious has a very secular dimension now. The mass marketing, the adoption of rock music, and things they thought were profane and secular 10 years ago, now they’re here.

KW: You’re talking about Christian rock?

MM: Yeah, things like that. Whoa man, they used to oppose that. The Elvis era and the devil’s hip movement and now, if you watch any of the channel 14, you get all of these evangelical shows.

KW: You do that for Lent? As penance?

MM: No, but after we’ve tried MSNBC, CNN, and there’s a fund drive on, and all these other things, there’s nothing else on and these religious shows are also extremely secular.

Marty: So you talk about anything secular and there’s something religious tucked in, and everything religious has secular tucked in, but you can’t form constituencies out of that.

Woodward: Let me try a different view.

MM: All right.

KW: It’s that political allegiance, and not to a political party, but the ideology. Liberal versus conservative, and where you are socially, which seems to fuse so many dimensions of a person’s life. The political, the social, what class they are. And we are just more divided than we have been before. And where you stand on gay rights and gay marriage and transgender determines your sense of who you are, over against the other people, regardless of what their religion is.

MM: Well, secular has the advantage of, you don’t have to make a commitment. And I can’t get over how often people use religious language when they talk about the Cubs and pro football. You could make a list of six or eight things that we call religion — ultimate concern, the quest for people to share it, the search for community, rite, ceremony, metaphysic, the belief there’s some force behind this — that God had to have a hand in it, that God really worked hard to get the Cubs that far.

KW: Yeah.

MM: I think the languages bleed into each other. I think one word we haven’t used that is there also is the cultivation of indifference. You have a very hard time preaching hellfire to anybody today; it ain’t going to happen. I think they take ultimate concerns, but it doesn’t focus along these lines. It’s done in — what you’re describing — the polarization of society.

KW: Just within the Catholic sphere the polarization is enormous. Catholics will say to their opposite number, “You think being Catholic entails the following things, but I think it’s quite the opposite of that. I think being Catholic means supporting Trump,” or whatever the issue might be. That’s what I'm getting at. I think the control is not Catholic; it’s all the other issues that are out there.

MM: I think this whole conversation is based on the assumption that that doesn’t quite work.

KW: There are a lot of grandparents and parents, the next generation, who see a loss in religious identity. It’s not the thing that comes up first when people declare who they are. That’s one thing — that self-identification. And anymore, you don’t even have to claim to be anything. That’s where we have the “nons.” After several generations of identifying only loosely, because that’s the way they were brought up, people are now free to say and millennials are saying, “none of the above.”

MM: But by any definition they make a religion out of it.

KW: Out of being a non?

MM: Yeah. When they form groups.

KW: Well. In that sense, you can never get away from religion because religion is a group formation phenomenon.

MM: You’ve got to have rites and ceremony and other things to go with it.

KW: Yeah, well . . .

MM: I just think that pluralism is bigger than secularism.

KW: But some say, “Look we are secularizing just as Northern Europe is, only we’re 20, 30 years behind.” And so there will be these constituencies, but they’re not going to be at the center of who these people understand themselves to be.

I’ve come to the conclusion that at best 20 percent of Americans will put religion somewhere at the center of their lives.

Let me put it another way: If you could ask a question in a poll that would get at the individual’s religious imagination or the lack of it by saying, “What world do you live in? Do you live in a world where the decisive thing — we just celebrated Good Friday and Easter, that this is at the center of history — well, is it the center, in some way, of your life?” Or are we in an evolving, purposeless universe?”

What is the big picture for them, what is the mythos? I don’t think you’d find many people that would revert to religious ideas and images.

MM: But every time there’s a death, the ceremonies are all extremely religious. Because they have to come to terms with something they don’t have to in their daily life. But it’s indifference most of the time.

Woodward: Let me go back to the people who have seen enormous changes in the relationship of their children and their grandchildren to the Church. The formation is just simply not there the way it was. And I think the same thing happened to liberal Protestantism — the disappearance of social boundaries that were labeled religious. Within those environments, you could learn what it meant to be a Lutheran and how that was different even from other kinds of Lutherans. Much less against the Catholics, or the Baptists and so forth. Those social boundaries disappeared.

And I think a lot of the lack of formation is because of the disappearance of those boundaries. The Catholics foolishly got rid of the discipline of meatless Fridays, which was one badge, and you’ll even find ex-Mormons who still don’t want to touch a drink because the taboo was instilled early. Well, you’d like to think that there’s more than community; formation is more than just communal formation.

The flip side of it, however, is that just the other night we participated in a seven last words of Jesus devotion. And you were the Lutheran there, I was one of two Catholics, there were three or four other Protestant clergy.

Marty: A couple evangelicals, a couple mainline.

KW: Yeah. We wouldn’t have done that in our day, or that would have been crossing over boundaries that you didn’t do. But who can’t count that as a plus, being able to draw on all of these different traditions for a larger vision of the church catholic, if you will?

Maybe certain points of division don’t deserve preserving. So I don’t know where we are on that, except that sociologically, boundaries matter.

Woodward: If I romanticize the past, part of it was growing up and going to Catholic school and all of that, and I said we were separated by a membrane, by identifiers.

I’m a person that, we do this or we don’t do that. That’s what I don’t see — the younger generations, that’s not where they are. They wouldn’t think of themselves as belonging to a group that does do this or doesn’t do that. To me the common denominator religion today is volunteerism. It’s service. It’s now obliged of high school students, if they want to get in to college. Everybody is doing it, it’s not special to religion. You don’t need to be a Christian to volunteer and do service and all of those nice things.

So to rely on that, as a way of passing on a tradition, seems to me shortsighted.

MM: Volunteerism is a way to get people serious; you get serious about religion through volunteering. But you’re right; you could make a religion out of volunteering and let it end there.

KW: Well, you can make a religion out of everything, and that’s actually taking place. Young bodies aren’t interested in doctrine and things like that. But I go back to the idea of a religious imagination, where you can see the exercise in literature of a religious imagination. It’s hard to conceive how to connect the Christian story or myth with what’s going on.

Ken Woodward

Ken Woodward

Woodward: Let me ask this, where is somebody like a Merton or a Dorothy Day? These are people who created their own place, who separated themselves from society, and yet they didn’t. They weren’t separate from the society at all. Is there an arrangement between the secular and sacred there that is recoverable?

Where can we form our children in a strong Christian perspective — whatever tradition we’re talking about — and, in a certain sense, defend ourselves against the invasive nature of the digital media? The cell phone is constantly with us; there is no island. You’re always part a network. Invasive is the word. We’re invaded. There’s no way you can keep the culture out. Even the Amish probably have cell phones.

Marty: I have a flip top by the way. It embarrasses my kids.

KW: Would you [turning to the photographer] get a picture of his flip top?

MM: I don’t ever use it.

KW: Now that’s what I'm thinking. People of our generation knew a kind of separation, and understand themselves as standing in a place in relation to all of this, and even still have the ability to turn it off — like you did with your flip top. But kids don’t. Young people today don’t. There’s no way you can separate from that.

MM: But I think that’s the very thing that militates against a Mother Teresa or Dorothy Day or Thomas Merton emerging today, because you’ve got a million little things that are going yesterday and gone tomorrow.

KW: You mean they only get their 15 minutes and that’s it?

MM: Yeah, and you really, really, really had to work to follow Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton.

KW: So they’re not willing to put in the work. The incentive is not there.

MM: Why bother? It’ll be gone tomorrow.

KW: So, the ephemeral nature of human existence, right? And yet, young people do want to be part of something. For them to establish the markers in their own lives of adulthood. Which is to say a fairly steady sense of career, even though you may jump jobs, you’ve got a sense of what you can do — and even that’s jittery today, the marketplace is so different. You’ve settled with one person, you’re married and maybe you have a child. And you’ve got some kind of investment in something.

It’s only at that stage that young people have sustained relationships with adults. Because increasingly they don’t do it in a lot of the colleges, not with their professors, it’s at arm’s length. Even their grades come digitally to them. They’re separated from the outside culture, especially if the campus is more plush and more inviting. So it’s kind of a preserve. You want to do something on television at night, just take a microphone and go on a college campus and ask the kids where Syria is or Afghanistan, or who Ronald Reagan was. It’s not a place where they’re learning the past, and they’re not even learning what’s going on in the present.

MM: When we were young, did we know who Calvin Coolidge was and Warren Harding?

Woodward: There’s must be a reason why there are no public religious ideas or figures in the public domain.

Part of it, it seems to me is the change in media, how information comes to people. How they can click out and not even pay attention to things because there’s nobody to tell them, “In the culture, this is what you should pay attention to.” Except their friends. Which means they’re not likely to come across something that’s outside their interests. Which contrasts with the era that you and I knew, because we put somebody on the cover of Newsweek or Time, or it appeared in The New York Times, that you paid attention to it because you trusted these organs of information to know what they’re talking about, and by definition provide a distillation of what’s important in the whole week’s news.

Today there’s no looking outside yourself to anybody, and that would be called elitism, to tell you what’s important, what you should know about.

I’m looking at the institutions. This is a very Catholic thing, I suppose, I come from institutions in the community.

Marty: Yeah.

KW: Because without these things, you have chaos. The family is an institution. But the family as an institution is not strong, and yet it’s the one institution the kids are more dependent on because that’s where the money comes from to go college, that’s where, if the parents are paying attention while they’re in high school . . .

MM: You sometimes even have affection.

KW: I once wrote a book with a child psychiatrist on the grandparent-grandchildren relationship. And over the long period of human history, the nuclear family — with only two people, mom and dad — is an aberration. And sometimes it’s only mom there who is so central to their lives. And that makes for a frail institution, as opposed to tribes, clans and so on.

How about neighborhoods, that’s an institution. Here in Chicago they still talk about ethnic neighborhoods. But I think in a lot of places, including suburbs, you don't have neighborhoods, for the simple reason a neighborhood is a place where up and down the street the people who live in the houses know you by name. But there’s nobody in the homes because they’re both working.

MM: Neighborhoods have changed that much. We were talking recently; I think there were 18 Lutheran churches within a mile circle in the Lincoln Park area. I think there are two of them left.

KW: I grew up in concentric circles of belonging.

MM: That’s right.

KW: Well, I will say this, I am from the Midwest but I spent 40-plus years working in New York.

MM: I know, you were corrupted.

KW: And New York is different. Or put it this way, Chicago is different. It’s still in some way a Catholic town. When I was at Newsweek, it was the Catholic bureau. If you went south, it was something else.

Marty: Good things can happen on the secular side, but it doesn’t answer the deeper questions you and I are interested in.

If you look at The New York Times, and like you said, people consider it a secular paper. I consider it a paradigm of secularism. Religion is really not important. I’ve never felt, with certain notable exceptions, that it was ever done very well there. Because the newsroom culture is such that religion is on the periphery of interest. It’s not connected to the people who run the place. It’s not connected to the people who are writing and editing for the place. And when they do get little bursts of interest in religion, all of these people in New York are surprised by it. There are a lot of religious people in Manhattan, but they’re not on public view, in a way.

MM: Yeah.

KW: And I can’t explain it. Whereas in the Midwest, that is still possible.

MM: There about 1,600 people in this building, which is more than lived in the town I grew up in in Nebraska. If you’d ask the desk man today how many people looked like they were going to church on Easter yesterday, very few. More Cubs caps.

Woodward: The present religious scene — are there any other eras that you would compare it to? In American churches and religious history?

Marty: Greco-Roman empire at the time of Christ. Really. Edward Gibbon estimates there were 10,000 religions in the Roman Empire. This is before Christ was born. They involved every god. Are their neighbors worshiping the same one? No.

KW: Are you saying that with the arrival, since 1968, of a lot of Buddhists and Hindus and so on, including the Dalai Lama’s crowd from Tibet, and Muslims, are you talking about all of these people and including that in your Roman Empire analogy?

MM: I’m just saying there are a lot of loose attachments now. And you have to select your god.

KW: I see. Selectivity.

MM: Yeah. From 313 until 1789, it wouldn’t have been this way. You would always have an official religion.

Here are some 19th century maps, and this was what we call Germany, which was founded much later. This was the time of the Reformation. Everybody in this area would be whatever it would be. [Pointing at a map] They were Lutheran. And then these toward Switzerland, they were Calvinists. Everybody in Switzerland had to choose that. My ancestors, all of the Martys, were from Switzerland. Therefore, they were Calvinist Reformed, with the accidental name of the Evangelisch. They moved to Nebraska. And what are you? Evangelisch. That’s why I am Lutheran. Made that great decision.

Chicago was the most ethnically pocketed city there was. You knew what side of the street was Croatian, what side was Serbian, all that.

KW: In the beginning of my book I talk about embedded religion, which is religion that goes with the landscape and . . .

MM: Which I think is one of your best phrases, it explains a lot.

KW: Well, the context in which you got religion determined the kind of religion you got, getting it by osmosis because we and our family are “X” and most of our town is that way. That’s one thing. But as you know, those towns are fading and so now we’re in a building like this. It’s not the same as being in a town.

If I romanticize the past, part of it was growing up and going to Catholic school and all of that, and I said we were separated by a membrane, by identifiers. Fish on Friday was one, the Catholic school system, these things. A friend of mine who grew up in suburban River Forest, Oak Park, he said, “What do you mean a membrane? Hell, there was a wall. We never dated girls from other schools.”

MM: I lived there in those years. I know that.

KW: So I don’t know. Just as the University changes and can’t be a centering place. Notre Dame tries, I mean they’ve got atmosphere, it reeks of atmosphere and constantly invoking a tradition, even at the same time they’re looking more and more like the other places. That’s what a research university does. I suspect very few of the faculty are as devoted to the University in the way the previous generations were. Because the thing they are to be devoted to has changed, and all of higher education has changed. If we’re talking education as a marker of identity, very few kids are in parochial schools. Are they not?

MM: There are very few parochial schools.

Marty: The strange reaction in Catholicism is another thing. I was with somebody recently who said that the new seminarians are the most rigid, and some Lutherans, too. You’re going there to flee the world.

Woodward: Free the world?

MM: F-L-E, flee the world.

KW: Oh, flee the world.

MM: Lutheran seminarians never used to wear a clerical collar, they did that when you’re ordained. And, that becomes the badge of an officer. Catholic seminarians, looking at pictures coming out of St. Mary of the Lake [seminary] . . .

KW: I haven’t looked at them, but this was the complaint back in the ’80s. Already, they were saying these kids coming in are clerical, they want to distinguish themselves by their garb.

MM: That’s the Catholic view in America, very much so.

KW: But I thought that passed now, that the model was more of service rather than anything else. The one thing that’s happened in Catholicism over the long haul of Vatican II is the lay involvement is extraordinary, people and even most priests have learned they’re not going to do much if they don’t have the committees and all of those things to do this stuff. People have really taken over an awful lot of these functions, and that’s a very good sign.

MM: Because it’s true, again, in River Forest, Oak Park, St. Edmond, north side of River Forest if I remember the name of it. St. Vincent Ferrer on Lake Street there. They are vital places, most of them have schools, they are declining no matter what, again, families are smaller, fewer kids around. Fewer nuns.

KW: There’s hardly any nuns. Here’s the test that I often do. There was a book called Can We Be Good Without God? Do you remember that?

MM: Yeah.

KW: And of course you can be good without God, but that’s not what you’re being asked.

MM: That’s true.

KW: To be. It’s a call to holiness, which is a whole different idea, and at what point does somebody — whatever their tradition — come to understand that?

MM: Our theology teaches that you can be good without God. In Isaiah. Second Isaiah. Cyrus was the Persian leader, and a killer. I mean, a terrible guy. But he opened doors on the Jewish captivity. So . . .

KW: The righteous gentile.

MM: And it says, “My servant Cyrus the messiah,” because why? Because he served the right purposes. It didn’t say he got converted to be called that. Good things can happen on the secular side, but it doesn’t answer the deeper questions you and I are interested in.

KW: Here’s what I observe. I observe the generations have increasingly devoted more and more of their time and their energy to work. I thought I recognized, when I went to the Soviet Union, one reason why the church survived despite great pressure on “Dare not go there.” First of all they were places of beauty, where Soviet architecture was just so grim from beginning to end. It wasn’t work. There was something to go to, there was a way of being for a while there.

MM: Sabbath.

KW: Sabbath. Sabbath. And also with the transcendent, in some way it survived — because kids, partly because these machines make them available 24-7 to their employer or their client, think, “I’ve got to find relief from always having to schedule, always having to prove myself.” It’s almost like in Latin America, when evangelical churches grew because these people were at the bottom of the social and economic pyramid, there’s one day a week where they could be a deacon.

MM: And the huge flourishing in West Texas of Pentecostal Hispanic pastors. Think of that cultural shift.

KW: And now that there are so many Pentecostals in various stripes, there is energy coming out of that.

Woodward: Here’s another point: Very few of the mainline publishers are publishing books that have anything to do with religion. It’s almost like the journalism we were talking about, and the stuff that sells is How to Cope — how to cope in a really strained and stressful work world.

Marty: With pluralism, religious secularity, digitalization, indifference, you’re just so overwhelmed by things that what are you going to commit to? And they’re huge things that I don’t see a way out of them yet. I’m back to Ortega, “Change will come if the crown of the human heart tilts ever so slightly.” And that can happen, but it would never take the form that it took, there’s nothing to go back to.

KW: We can establish that. But I still insist there has to be some kind institutionalization. I don’t care what the arrangement is. That’s what I was getting to, for the growth sector in American religion, to the extent that there was one, was Pentecostal and nondenominational. And now they’re creating networks, not quite denominations, but they find they do have to network in some way. I’m very fascinated by that.

So the denomination, how alive is that? And if you say, if somebody says to you, “I am a Methodist,” how much does that tell you about that person? And then you have to say the same thing about Catholics. If somebody tells you they’re Catholic, “Oh yeah, well then, what kind?” You know? And that wasn’t the case.

MM: But let’s go back to something I had in mind before when you were talking about the ’50s. I did my theological internship in Washington, D.C., for two years. And that was right near a Presbyterian church, and they’d been debating in Congress about making the pledge of allegiance under God, and the Presbyterian minister preached and said if you read the Soviet constitution and our constitution, they look just the same. We should have God in there. That was Sunday morning, by Tuesday morning they voted unanimously. The culture was just that hungry. You’ve got to have “under God” in the constitution.

KW: Well that reminds me, we had an adversary and they were atheists. And there was all of those fears. So I guess what I’m saying is that they’re going to be persecuted by this and by their work week and all that. And there will be no leisure — because even leisure is hurried in a sense. But at the same time, when religion is persecuted, it thrives.