Last year on the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows, the patronal feast of the priests of Holy Cross who founded Notre Dame, I walked over to the Grotto to pray for the University and myself as a scholar and teacher here. It was a beautiful September afternoon — technically still summer, but cool and sunny, giving a foretaste of approaching fall.

It may surprise some, but I often go to the Grotto to work as well as pray. It’s a little known fact that Notre Dame’s wireless network functions down there if you sit on the bench next to the statue of Tom Dooley. So visitors will sometimes observe a middle-aged professor, iPad open, Fourbucks in hand, working away under Mary’s gentle gaze.

I used to smoke a cigar as I sipped my coffee and read or typed. But a colleague, a cigarette smoker, thought it was offensive of me to do so. I’m not sure of that, as any good cigar smoker knows the honor we do another by smoking a fine cigar in his or her company. I should have reminded him of the old Jesuit who responded to his penitent, “No, you may not smoke while you pray. . . . Of course, you may pray while you smoke.” Still, out of deference to the feelings of those who don’t understand the beauty of a good cigar, I no longer do that.

Another reason to work at the Grotto is the opportunity it affords to stroll there and back through God Quad, particularly in the spring when the lilacs are in bloom and the atmosphere is filled with their scent. It has perhaps been noticed by some passersby that a professor can upon occasion be seen head buried in a lilac bush, inhaling as if he cannot catch his breath.

I remember one such afternoon coming across a tour setting out from the Dome. The student guide was standing in the square in front of the Dome, the Basilica to her left, Washington Hall to her right. The tourists gathered around her had their backs to the Dome and were looking toward the statue of the Sacred Heart 50 yards away, with Christ’s arms outstretched and the inscription, Venite ad me omnes — Come to me, all.

The guide did not tell the usual joke about Jesus yelling up to Mary, “Jump, Mama, jump!” In fact, she didn’t mention or even indicate the statue of Christ behind her at all. Her back to Christ the entire time, she explained that God Quad got its name “because of the statue of Mary up on the Dome.” Her spiel over, the guide hurried her tour on toward the library.

It’s a small thing, this turning of the back to a statue of Christ. But potentially it carries great symbolic weight for the University. For in taking the time to stand and look, we see things in that quad which tell us about our University, remind us of those who founded it, suggest to us what we may be and what we may fail to be.

One day in class I discussed with my students a passage in which Nietzsche, the 19th-century German atheist, remarks that in our time, “our noisy, time-consuming, proud and stupidly proud industriousness educates and prepares precisely for ‘unbelief’ more than anything else does.” He goes on to point out that modern times have reduced all of life to a business or a pleasure, and the problem is that we can’t figure out whether prayer is a business, a pleasure, or both. One of the most interesting features of the class discussion was students’ use of the phrase “make time,” as in “I want to make time for my family” or “I want to make time for prayer.” With Nietzsche in mind, I asked them why no one ever speaks of “making time for work” or “making time for the football game.”

I also asked the students what it would be like not to see oneself as a kind of lord of time, one who “makes time,” but instead as one who receives time as a kind of gift. And I asked them to reflect upon how the way they speak about these issues may make Nietzsche’s point. What Nietzsche wants us to recognize is that we have lost the notion of leisure — genuine leisure. Not the leisure that is merely a rest from our business designed to “recharge our batteries” so we can resume being industrious, and not leisure for the pursuit of pleasure, but what he calls “leisure with a good conscience.” This is a kind of leisure that allows for contemplation.

At Notre Dame this could mean the contemplation of a woman clothed with the sun at the Grotto, a leisure that does not feel the demands of time moving the tour along but the gift of time that allows one to stand at Christ’s feet contemplating what venite ad me omnes requires of one.

That’s why I work at the Grotto and stroll God Quad. In the leisure of my work, I pray more.

God Quad

Talking with the students about Nietzsche’s astounding claim about prayer, I began to describe God Quad for them, taking them on a more leisurely tour than the one visitors often get. I reminded them of “Jump, Mama, jump!” since being prayerful does not exclude having a sense of humor. But I pointed out that with the growth of the University’s physical plant, much of the symbolic character of God Quad is lost to us today.

This loss of symbolic meaning illustrates Nietzsche’s argument that the modern Christian continues to employ a vocabulary that in reality has lost its original meaning. This is one way of understanding what Nietzsche meant by proclaiming the “death of God”: Christians themselves no longer really believe in God, although they don’t quite recognize their practical atheism yet because they continue to employ a Christian vocabulary that is a mere ghostly remnant of the past and fails to embody its original meaning and claim upon their lives.

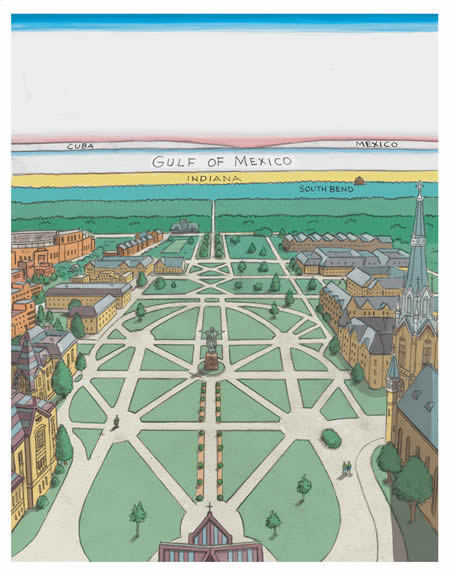

I explained to the students that if they had been on campus 80 or so years ago, what they would have seen from God Quad was how the University had been laid out in a cross. South Quad forms the horizontal of the cross, while God Quad, heading south from the Dome to the Main Circle, forms the vertical. Visually, Mary on the Dome stands at the foot of the cross.

Nowadays a more modern statue of Mary stands in the Main Circle — at the head of the cross. Since there is nothing intrinsically wrong with the modern, this too works as a symbolic representation of time and place. If Mary upon the Dome stands at the foot of the Cross as on Good Friday, at its head she welcomes campus visitors and directs them to her son, the Christ who stands in the middle of the cross. Come to me, all per Mariam — through Mary. It is an unmistakably Catholic welcome to the campus and what we do here.

The symbolism does not stop there. The statue of Christ is the image of the Sacred Heart, a campus devotion best known in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, where Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross is made truly present each day. And the curved sidewalks that proceed and bend outward from the square in front of the Dome and around the statue of Christ come together again at a point above South Quad. From the air these pathways form a heart, the Sacred Heart, with the statue of Christ in the center.

As I explained all of this to the students, I was gratified to hear a few oohs and ahs and even a soft, “That’s cool.”

All of this, however, is now obscured by the expansion of the campus. This is not a rant against the growth of the University. It had to grow, both in terms of its physical plant and its aspirations for scholarship and teaching, if it was to fulfill the promise that Father Sorin discerned in founding it. Still, even to many who know the campus well, that plan of the Cross and the Sacred Heart is gone.

Pursuing truth

The loss of the visual meaning of the heart of the campus can be instructive in thinking about the University. The essential character of any university is to be a place of scholarship and teaching, studying the world that God created in the beginning, redeemed through the incarnation of Jesus Christ, and calls back to Him in the end. Like Mary’s welcome in the Main Circle, this description of the task of a university is decidedly Catholic and Christian, premised as it is upon the truth of Catholic Christian faith.

Nearly everyone, believer and unbeliever alike, will agree that the task of any university is to pursue truth wherever it may lead. But since God created all things, redeemed them through his death and resurrection and calls them back to Himself in the end, how can any university claim authenticity if it does not pursue that truth? Indeed, even those people or institutions that deny the truth that God created all things, or are even just agnostic about it, are not absolved from pursuing the possibility of its being true, any more than someone who denies that the world is spherical is absolved from finding out the truth.

So, to the extent that any university cuts itself off from that truth, it fails by the standard of what it claims is its essential mission, to pursue truth wherever it may lead. Nietzsche, for all his atheism, might say that in shrinking away from God such a university fears being great — it does not have a “good conscience.”

The truth of Christ, creator and redeemer, gathers all other truths and the disciplines that study them within its scope. Thus the reason the University had to grow is not so we could be like everyone else, but so we could be true to the promise within Notre Dame to embody the genuine character of a university. Notre Dame had to grow in order to show the world what a truly great university could be. It had to grow in order to be a gift of the Church, from the University’s heart in the center of the campus, to a world badly in need of it.

It matters a great deal whether one is looking to become great, or whether one is already great and looking to enrich that greatness. Being committed to Christ and the Church is no guarantee of excellence in the pursuit of truth, so to be true to itself, Notre Dame has had and must continue to draw within itself those who are best at pursuing truth in the various disciplines, even those who are not committed to Christ and his Church. She cannot live up to her greatness without beckoning them all to the Christ who says, venite ad me omnes.

And yet, will the intellectual growth of the University obscure from it the truth that makes it truly great, the truth that sets it free from subservience to what are often no more than ephemeral academic fashions? Will Notre Dame, like the tour guide, turn its back to Christ?

For all its need to draw academic excellence within itself to fulfill its promise, Notre Dame is great because of its commitment to Christ, who is the beginning and end of all things. This is an institutional commitment to a truth that engages the intellect and cries out to be explored and understood in relation to all other truths. The mistake is to think such a commitment is opposed to or stands apart from academic excellence. On the contrary, it is integral to it. Drawing within itself those aspects of greatness found in other universities does not make Notre Dame great; rather, it fulfills and enriches the greatness Notre Dame already embodies because of the University’s foundational love of Christ and His Cross. So, to be truly great, to pursue truth wherever it may be found, the University must also be animated by those who think it is in fact true that God created, redeemed and calls all things and everyone back to Himself.

Some fashions in academic life, however, find talk of truth and the pursuit of truth to be threatening, and they fear it. They think the word “truth” does nothing other than mark out a favored position of the powerful for controlling and doing damage to others. We ought to acknowledge the grain of truth in the fear that quite often claims to truth can be like clubs for beating others with whom one disagrees, and not invitations to a kind of life of inquiry together. And that is why the university cannot simply be animated by those who think it is true that God created and redeemed the world. With Saint Augustine we must live “in omnibus caritas” — live in all things the love of God. And so at the center of the cross in God Quad we find, if we stand and look, that we are beckoned by Him to His Sacred Heart.

A different kind of difference

University President Rev. John Jenkins, CSC, ’76, ’78M.A. said in his 2005 inaugural speech that we cannot make a difference unless we dare to be different. At present the University, marketing itself to the world, is emphasizing the difference we are trying to make. Consider the football halftime commercials, which tend to concentrate upon the good Notre Dame achieves in the world through the efforts of its faculty, staff and students to improve the lives of the less fortunate, the sick and those who suffer from war, famine and natural disaster.

These activities are all very good, and they ought to be pursued. They are what the Church used to call corporal works of mercy. Yet in our emphasis upon how we are making a difference, might we forget the conditional character of Father Jenkins’ claim? He did not simply dare us to make a difference. He dared us to be different in making that difference.

And what might that being different be? Are we to believe other universities do not engage in good works? That only Notre Dame makes an effort to alleviate suffering? If that is so, then why do the commercials for the schools we compete against look so much like ours?

I believe our difference comes not so much from what we do, however good, but from where we stand — like John with Mary at the foot of the cross. Faith lived in caritas, the love of God and the love of one’s neighbor in God, makes us different, and it is precisely that faith, that truth, that makes Notre Dame greater than other “great” universities, that faith that says to believer and unbeliever alike — and all of us sinners — Come to me, all. That is our hope.

We are united by that faith in a kind of friendship. My students also read a work by Josef Pieper, a German very different from Nietzsche, on the nature of happiness. Pieper asks what would happen if we succeed in alleviating all human suffering. Would we then say our job is done and leave people as healthier strangers? G.K. Chesterton called this “the humanitarian ideal” and joked that it is akin to those who love mankind and hate their next-door neighbor.

Pieper’s answer is that we do these things in order that we may enjoy friendship with those we help. “Good works” are insufficient without friendship — and not just any friendship. Pieper cites Thomas Aquinas in calling it a “companion in future beatitude.” This kind of friendship means we are all John, Christ’s beloved friend, told by Christ that Mary is our mother, that we are all brothers and sisters of and in Christ. Those we help by good works are our friends, not to be left alone when we have completed our work but to be lived among as fellow images of the Christ who calls us to Himself.

That is why our good works, our difference, is different.

That is why we stand where we do. Where we stand changes everything, and everyone. There is no truth left untouched by its truth, and no pursuit of truth in good conscience without it. As we tell the world how we go out to make a difference, we need to remind ourselves of how we are different, of where we stand. Otherwise we run the risk of being “proud, stupidly proud,” engaged in nothing other than an education in unbelief. As a community of inquiry into truth wherever it leads, a companionship in beatitude, we participate in one another’s achievements, both the achievements of those who go out into the world to make a difference and the achievements of those who stand still to inquire into how we are different and what difference that makes to all that we do.

Perhaps we ought to have one commercial that doesn’t ask “What would you fight for?” but instead, “Where do you stand?” If you’d like to talk about it, I’ll treat at Fourbucks, and we can walk to the Grotto. On the way we’ll stop in the middle of the Sacred Heart to look around and maybe smoke a fine cigar, contemplating Christ, who invites us here.

John O’Callaghan is an associate professor of philosophy and the director of the Jacques Maritain Center at Notre Dame.