How Notre Dame came to be home to a treasure trove of long-buried documents that provide an intimate and previously unknown accounting of the Russian Revolution.

Nicholas II, last of the Romanov tsars who had ruled Russia for 300 years, was an autocrat whose waning authority rested upon impenetrable bureaucracy and repressive police action. In the brutal winter of 1917, protests against the monarchy and Russia’s involvement in the First World War boiled over into a soldiers’ mutiny in the Russian capital, Petrograd. Within days, the Tsar abdicated,a coalition of liberal and moderate socialist politicians formed a provisional government, and an array of socialist intellectuals assumed the leadership of the Petrograd Soviet, an assembly representing hundreds of army units and factories. One socialist faction, the Bolsheviks, had long envisioned a two-stage revolution that would first remove the Tsar in favor of Western-style democracy and then arm radicalized workers to overthrow Russia’s wealthy elites. At first they formed only the third largest faction in the Soviet, but they were not finished. For them, the “February Revolution,” in one historian’s estimation, “was a mere prelude to the ‘true’— that is, socialist — revolution” that would come in October and, after a civil war, beget the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922. — The Editors

It was winter, 1917. The Russian Empire was disintegrating.

The last Tsar was mired in a world war in which his leadership inspired no confidence at home. Casualties were in the millions. Morale was in the mud. Desertions multiplied, pogroms spread, war debts continued to mount. In her splendor, the Tsarina alienated the political counselors of the Duma (the Tsar’s national parliament), and Mother Russia faced a new year of famine, mutiny, inflation and strikes. In March, Tsar Nicholas II heard reports of Petrograd in anarchy. Urged by his ministers, he soon abdicated and was placed under house arrest by a provisional government composed of leaders of the old Duma and a new worker’s council, the “soviet.”

The advocates of democracy enjoyed an exhilarating spring that lengthened into a challenging summer.

Then came the Bolshevik autumn. Problems had not been solved. Factories had continued to close, foreign debt was in the billions, the war was still raging, and there were worker strikes and military mutinies as far south as Baku. The Provisional Government wanted to finish the war, but workers and soldiers had had enough. Demonstrations were put down by the government with gunfire. Some Bolshevik workers’ leaders were arrested. Enraged, workers’ councils turned to the Bolsheviks, first in Petrograd and then seemingly everywhere.

On October 24, the Bolshevik Central Committee declared the time was right for an armed uprising. What followed was civil war, mass executions, forced collectivization, the rise of monstrous Stalin, and the rewriting of history to enforce a single narrative: the fall of the Tsar was led by the vanguard of the glorious Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

What happened to the voices of spring and summer? Silence.

But in the provinces, evidence has a way of enduring. Historians have long known that a historical commission was set up in the spring of 1917 to document the revolution which deposed the Tsar. That commission may have recorded firsthand accounts from the participants themselves, which would offer the best possible source of evidence regarding their designs, proposals and motivations. Did such testimonies survive the long Soviet winter? If so, where were they?

You are among the first to know.

Windows in Moscow

By 1992, the USSR had disintegrated.

In the heat and exhaust of a summer afternoon in central Moscow, a doctoral student at Stanford University named Semion Lyandres stood shoulder-to-shoulder with fellow historians in the cramped reading rooms of the Central State Archive. They had all come to open boxes that had been closed for generations by the enforcers of official narratives. Lyandres was checking the main lines of his research on early Bolshevik ties to German money. He was also keeping an eye out for any references to a historian named Mikhail Polievktov (1872-1942), whose name was associated with the historical commission set up in 1917.

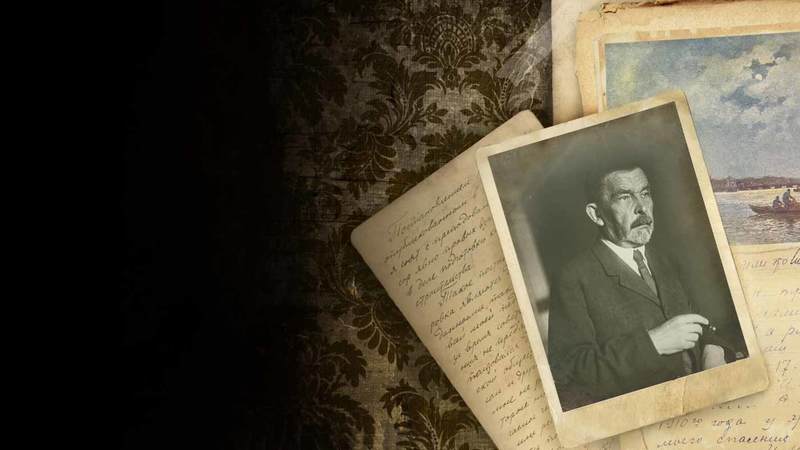

Polievktov was a well-known historian of pre-revolutionary Russia. In sepia photographs he appears stubbled and mature, looking sternly away, thick hands stained by a permanent cigar. In 1913, he married Rusudana Nikoladze (1884-1981), the eldest child of Niko Nikoladze, a leading Georgian revolutionary, patriot and the practically minded former mayor of Poti on the western coast of Georgia. Rusudana had a fine nose and careful eyes. Broadly educated, she spoke five languages, traveled extensively in western Europe, and earned degrees in physics, education and both inorganic and organic chemistry.

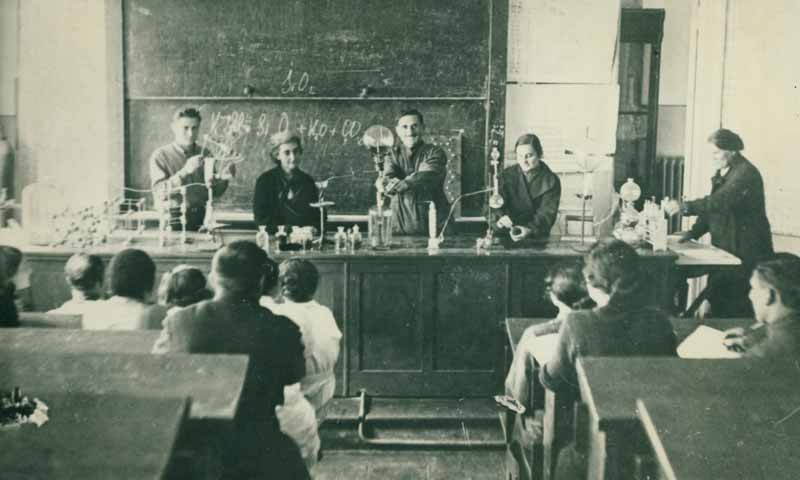

In addition to being a reflective teacher (she had studied the methods of Maria Montessori), Rusudana was a gifted writer and meticulous record-keeper — a diarist, memoirist and correspondent of the first order. She was teaching chemistry at the Women’s Pedagogical Institute in St. Petersburg when she met Polievktov, who sometimes lectured there. He gave her pearls. They were on their honeymoon in Europe when Russia entered the Great War. Rusudana recorded their arduous and circuitous journey back to Russia in precise, extensive detail.

The Polievktovs moved into apartments near the magnificent Tauride Palace in Petrograd. They had one child, a son named Nikolai, in 1915. Two years later, Rusudana and her younger sister joined their friends as telephone operators in the offices of the Petrograd Soviet. Now it was the Provisional Government checking their papers every day instead of the Tsar’s police. They were helping the new revolutionary democracy. It was early spring.

With a new chapter in Russian history underway, Mikhail Polievktov and a fellow historian had the foresight to establish a Society for the Study of the Revolution (SSR), a historical commission dedicated to documenting the events and recording firsthand testimonies. Mikhail was in charge of the SSR’s Interview Commission and recruited Rusudana, her sister, and their friends and students to help record them. Multiple transcripts were made of oral testimonies and taken down in pencil to be later compiled into neat versions in ink. These were kept in Mikhail and Rusudana’s apartment along with official papers, certificates, passes and their voluminous family correspondence.

In 1992, Lyandres and his colleagues knew only that the historical commission had existed; the whereabouts of its documents were a mystery. He had a hunch that the interviews might be found in some official archive, but seven years of searching for them had proved fruitless.

Then Lyandres discovered his first solid clue: a document in the State Archive of the Russian Federation written by Boris Nicolaevsky, a leading moderate Menshevik (from men’shinstvo, “minority”), stating that Mikhail Polievktov had delivered a report to The Society of the House-Museum for Preserving the Memory of Freedom Fighters in fall 1917. The report included a list of all those who were interviewed and disclosed that the original transcripts had been sent to Georgia for safekeeping.

The hunt was on.

Tbilisi Proxy

In an old tweed jacket and jeans, Lyandres has the virtues of an old-school historian: practical, patient, multilingual, intolerant of cant and imprecision. Born and raised in the Soviet Union, he speaks perfect Russian. Like Polievktov, he has thick hands that look like they can handle anything. When he talks, you think about forests, catastrophe, vodka and the truth.

After earning a doctorate in Russian and Eastern European history from Stanford, Lyandres taught history at East Carolina University for several years. His research had been focused on providing fresh looks at documentary evidence from 1917 and on the relationship between legal and political thinking in the Russian Provisional Government. Notre Dame hired him in 2001 as associate professor of history and co-director of the Russian and East European Studies program.

Around the same time, Georgia began to stabilize after a conflict with secessionist groups in its northwest. With his international connections as editor of the Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography, Lyandres searched for contacts in Tbilisi, asking everyone he knew whether there were reliable people in the Central Historical Archive of Georgia who could find the information he needed.

A recommendation produced a man who introduced himself on the phone as “Rezo.” Lyandres shrugs. “To this day, I have no clue who he is, maybe a state archivist.” He also had no idea where Rezo’s loyalties might lie or what Rezo might do with valuable historical evidence if he found it. Lyandres had to be careful. For $200, Rezo eventually answered a general query. Some of Polievktov’s scholarly papers indeed were in the historical archive. Nothing else; certainly no promising mention of the work of the 1917 historical commission.

Without being in Tbilisi, it was impossible to know whether Rezo was being fully forthcoming.

A few years later, Rezo told Lyandres that Rusudana had published a book of memoirs in 1975. What did it say? Rezo described the contents, unaware of what Lyandres was after. Lyandres heard for the first time that Rusudana had worked on the 1917 historical commission’s transcripts, and that they were still in the family’s possession in 1972. The trail was getting warm. Was Rusudana still alive? Rezo said she died in 1981. Any heirs? The Polievktov-Nikoladze residence was now in the hands of someone named Zinaida Leonidovna. Rezo had her phone number. Lyandres wrote it down, thanked his mysterious assistant and never heard from him again.

The problem now was how to reach Zinaida. Lyandres was reluctant to contact her because he had no idea how she would react to an unexpected inquiry by an American. He needed another proxy. “In early 2005, I was fairly certain that she had the transcripts, but she had to be approached cautiously.”

So Lyandres called a Russian colleague working at a historical institute in Moscow. “Let’s call him ‘Sergei,’” he says, adding only that he was a senior research fellow “with a superb nose” for documents. Lyandres approached him cautiously as well, saying he was interested in any documents that might be in Zinaida’s possession. Would Sergei telephone Zinaida on his behalf and inquire?

In her, the two historians faced a considerable figure. They had learned that Zinaida had married Rusudana’s only child, Nikolai Nikoladze. Like his mother, Nikolai had gone on to an illustrious career in the sciences, eventually working under Igor Kurchatov in the 1940s on the Soviet atomic bomb. Zinaida herself was a physicist and had been a student of Nikolai’s. He had died in 1989, leaving her in sole possession of the family apartment and all its papers. In response to Sergei’s inquiries, she faxed him a list of the interviews she had, along with their dates. Comparing this list to the one Polievktov gave to Boris Nicolaevsky in 1918, it became clear to Lyandres that Zinaida had the interviews he was looking for.

But Zinaida was no fool. For more than a year, she refused to let Sergei see anything or indicate whether she was willing to sell or reveal any offers she had had from others. All Sergei heard was, “I’m not ready,” or “Call me in a few months.” He eventually shouted at her in exasperation, “Send me a copy of just one page!” She retorted, “You can come see it yourself!” She also demanded an enormous sum of money. Then she hung up.

At the end of 2005, Sergei’s patience ran out in a stream of Russian expletives.

Zinaida had the interviews, but she wasn’t talking.

Surprise from a Friend

Family papers often emerge from the past in fragments to be sold off in pieces. Sometimes they shed light on historical events and sometimes their significance is decorative, confirming what we already know.

But sometimes the past can surprise us.

Early in 2006, Lyandres received a telephone call from a friend of his in Israel who grew up in Georgia, a biophysicist named Elya Fine. After catching up and heaving some mutual sighs about work, Lyandres related the story of his pursuit of some historical papers and a woman named Zinaida. Elya was interested. Whose papers were they?

The name “Polievktov” rang a bell. Elya had once heard a lecture by someone named Polievktov-Nikoladze, a Russian physicist with an unusual name that sounded ethnically Georgian. His lecture was so striking that Elya still remembered it. “I know him! I heard him lecture 30 years ago! He was different, important! This Zinaida must be his daughter — or wife?” He asked Lyandres to tell him more.

Polievktov-Nikoladze, Elya learned, was Nikolai, Zinaida’s husband.

Elya, a practical man, told Lyandres, “We need to find somebody to get to her as a local, and I can help.” Lyandres was skeptical, but Elya remembered some people who had also studied with Nikolai. “Let’s at least open this door and see what’s in there,” Elya insisted.

A month later, Elya recommended a man who also studied physics under Nikolai. The man agreed to meet Zinaida in the family apartments. He phoned her, and she invited him over. Lyandres had sent him a list of questions and instructions to examine, if possible, the coveted transcripts of the 1917 historical commission. Once inside, the man was able to see what he described as handwritten documents from 1917. He jotted down some details and sent them to Lyandres the next day by email.

Comparing the details with bits of information he had, Lyandres found the trail getting even warmer. “Will she talk to me?” he asked Elya’s contact. “Sure. She and I both went to Tbilisi University,” was the reply. “She trusts me.” During a second visit, the man asked Zinaida if an American friend of his could come and visit her as well.

There was silence. She would think it over.

The next day, she agreed.

How to Haggle at Notre Dame

Buying historical documents is delicate work, especially when the documents are halfway across the world in a region suffering the effects of war and infrastructural anarchy.

So Lyandres went to Louis Jordan, head of Special Collections at Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Libraries. “It was terra incognita,” Lyandres said. He asked Jordan where they could find sufficient funds. They worked on logistics right away. Lyandres tapped his own research account; Jordan worked with the library and Professor Jeff Kantor, then a vice president for research, who eventually helped the team secure the funding it required to make the purchase. But at the outset, Lyandres had much, much less.

And how could such funds ever be transferred from Notre Dame to a private citizen in post-Soviet Georgia where there was no reliable banking system?

Lyandres offers an understatement. “We had many, many meetings.”

One last logistical puzzle remained. Where would Lyandres get the funds to travel on such an unusual premise? Lyandres went to Notre Dame’s Nanovic Institute for European Studies, where director A. James McAdams instantly realized the importance of firsthand evidence of what happened in February 1917.

McAdams, himself a political historian, recalls the conversation. “It was a ‘can’t miss’ opportunity to become a major player in Russian revolutionary history. The evidence would allow us to see world-historical events from the perspective of the actors who made them. They couldn’t know what would come of their actions, but they were driven by the sense that they were on the verge of ushering in a new age. They were right.”

Says Lyandres: “In five minutes, I had all I needed.”

No one had any idea how large the return on this investment would be.

Meet me on Tabidze Street

On May 8, 2006, a Monday, Lyandres and Elya took separate flights to Tbilisi. Lyandres’ wife, Natasha, a Russian and East European Studies bibliographer at Notre Dame, was worried. “Georgia was not a safe place. I was very nervous, and he had to work secretly. What if he were stopped?” Her fear was hardly unreasonable.

In Lyandres’ jacket was a stack of traveler’s checks and a nonrefundable ticket. He took the midnight flight, the only flight to remote Tbilisi for a week.

Skirting the southern edge of the Caucasus, the plane touched down in Tbilisi at 4:30 a.m. There Lyandres met Elya, who had flown in from Tel Aviv. Citywide electrical outages were routine. In total darkness, they made their way to a rundown hotel near Zinaida’s apartment. The city was desolate. It was like that every day. “Even at 8 p.m., you felt like you were in the middle of the night in a field,” Lyandres says. Stray dogs roamed the streets.

They were in an old, formerly prestigious neighborhood called Sololaki. On Tabidze Street, forlorn and empty, Lyandres and Elya carefully picked their way to the Polievktov-Nikoladze residence. The apartment was on the top floor. Not knowing what to expect with Zinaida but with no time to lose, Lyandres and Elya went straight up to meet her.

Zinaida greeted them and led them at once into a dining room decorated with fading frescoes. She offered them tea and khachapuri (cheese bread). Next to the fireplace stood an old-fashioned space heater. On the walls were some early 20th century paintings. Doors led to adjacent rooms. Lyandres was nervous and exhausted.

After brief talk about Zinaida’s late husband and family, they went straight to business. About the commission transcripts, someone named “Rezo” had come years ago to demand that Zinaida transfer everything she had to the state archives. She refused. What else? “Many historians were after things,” a Russian named Sergei, for example. They never made it to her apartment. Why? Zinaida dismissed the question with rolled eyes and a wave.

Lyandres had been right to be careful.

Then she disappeared into an adjoining room. Lyandres looked around. The frescoes were almost certainly painted by a famous Russian artist named Sergey Sudeikin, who had designed sets for the Ballets Russes in the early 1900s and had worked on Nicholas Roerich’s designs for Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Whoever lived here moved in high artistic circles as well. Returning to the table, Zinaida produced a thick folder.

In it were the interviews from Polievktov’s commission in 1917.

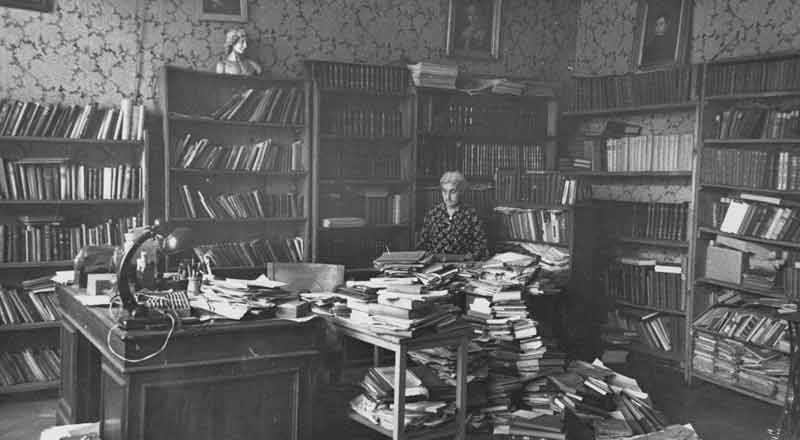

How to Haggle in Georgian

Lyandres reviewed them coolly. After answering several questions, Zinaida took the two men into the adjoining room, Mikhail and Rusudana’s private study. What Lyandres saw staggered him. Every bookshelf was full. The floor was piled high with papers, manuscripts, books, scrapbooks and letters. An entire family archive, three generations of revolutionary, academic and political life, containing not only the firsthand testimonies from 1917 but the family’s extensive correspondence with prominent Russian and Georgian revolutionaries, was right there in front of him, perfectly intact.

Lyandres is still amazed. “It was remarkable. The same arrangement of furniture and belongings was there for generations.” In the middle of it, as if 1920 never stopped, sat Mikhail Polievktov’s own desk from Petrograd. Mikhail, Lyandres learned later, had sent Rusudana and little Nikolai to Georgia to escape the turmoil in Petrograd. He, and his furniture, eventually joined them, having secured permission from the People’s Commissariat for State Security to conduct a temporary “research trip.”

Wisely, the Polievktovs never lived in Russia again. Georgia lost its independence in 1921 and was dissolved into the Soviet Union. Elected professor of history at Tbilisi University, Mikhail Polievktov lived for the rest of his life in that top-floor apartment, writing and teaching about Georgia’s international affairs. Unlike many friends and former colleagues with whom he kept up correspondence, he escaped Stalin’s purges. Occasionally he had to fight off personal smears made by Soviet officials in the Georgian press, but by and large he lived an active and respected life as a historian.

Standing in that study, Lyandres knew what he had in the folder and what historical treasures might be contained in the bookshelves around him. Facing Zinaida, his stomach in knots, he began a conversational dance. “Talking to Zinaida, it was like we were from two different worlds, two different planets.”

Lyandres knew the transcripts were valuable. Zinaida set an initial price, but with significantly less than the amount in traveler’s checks, he wasn’t prepared. He made a much lower counteroffer. They argued, morning till night. Zinaida once became quite indignant. “If David Beckham could sell one autograph for two million,” she told him, “aren’t these documents by great minds worth a measly twenty-five thousand?”

“We went back and forth like that the whole damn day!” Lyandres says. “She was absolutely stubborn.”

As the evening turned into night, Lyandres finally pushed back his chair and rose with a sigh. “I have to give the University an answer,” he said. Time was of the essence. It had been a frustrating conversation, and, he figured, probably the first of several marathons.

But Zinaida appeared disconcerted by his farewell.

She accepted his offer.

Looking at the vast collection behind her that represented three generations’ worth of materials from a time that changed the course of Russian and world history, Lyandres promised her that he would talk to the library at Notre Dame, nearly 6,000 miles away, about additional acquisitions and more money. In return, over the course of the week, she allowed him to examine and copy many documents.

What had caused her sudden reversal? Lyandres thought it obvious. “She wasn’t sure I would come back.”

The 1917 historical commission transcripts safe in his hotel, Lyandres visited the state archives where Rezo had (and may still have) worked. Conditions were appalling, even worse than those in Moscow: “It was the same devastation, the lack of state support, terrible conditions for those who worked there let alone for visiting historians. There was hardly any hardwood floors left in the hallways. The wood had been chiseled away and used for heating and cooking.” He shuddered to think what would have been the fate of the Polievktov interviews. Even if they had survived, access would have been difficult: “The archives were only open four hours a day. It was impossible.”

So Lyandres left Tbilisi with the interviews in his carry-on bag.

How did he get it past customs? “[I] just put it in the machine,” he marvels, as if they were a bag of socks. If any questions came, he had prepared answers. But none came. “I was very green,” he admits. “There was a huge risk in losing such a valuable archive. Of course I made copies beforehand, and I scanned some. I also made copies for Elya, who later sent them back. We took different flights, to see who could make it through.”

What would the Georgian government say?

Lyandres puts on his black sunglasses. “What could they say? This was a private family archive and a perfectly legal transaction. Besides,” he says with a smile, “I have no immediate plans to travel to Georgia.”

From Tbilisi to Notre Dame

When his plane touched down in South Bend, Lyandres let out a sigh. “I called my wife and said, ‘That’s it. I can have a drink.’”

But the process was not over, not by a long shot. What Lyandres had found in the apartment was far larger than a folder of interviews. These interviews were indeed precious. They also included a firsthand account of the arrest of the Tsarina by Captain Nicholas Krasnov and a long interview with Alexander Kerensky, then minister of justice in the Provisional Government, which is now his most expansive testimony of the February Revolution.

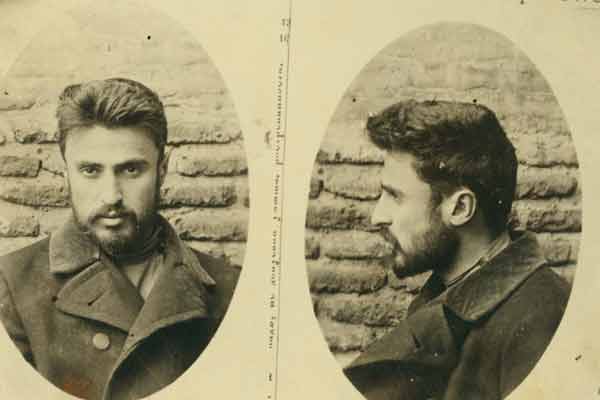

But there was far more in the study, as Zinaida well knew. The archive contained unpublished manuscripts, genealogical and organizational charts, dozens of diaries, scrapbooks containing postcards from revolutionaries exiled to Siberia, police mug shots, official passes, questionnaires, certificates, rare first editions, hundreds of photographs, and extensive correspondence between members of the Polievktov and Nikoladze families and prominent Russian and Georgian public figures, many of whom were later executed by Stalin’s secret police. “Would you be interested in something about Tsereteli?” Zinaida asked Lyandres at one point, knowing the answer would be yes.

Raised by two of Rusudana’s aunts in western Georgia, Irakli Tsereteli (1881-1959) studied law at Moscow University but was arrested for leading student demonstrations against the Tsar. Sent to forced labor in Siberia, he returned to Russia during the 1905 Revolution and was elected to the second Duma. Arrested again for high treason, he was sent again to Siberia with fellow agitators. Who corresponded with him and visited him regularly while he was in prison? His cousin, Rusudana Nikoladze. She preserved his letters and notes written on cigarette papers in her personal scrapbooks. Moreover, she served as a courier between Tsereteli, his colleagues and their defense attorney in Petrograd. With affection, Tsereteli sends her “passionate kisses” and calls her “the Talleyrand of conspiracy!” All this is preserved in loving detail.

Alyssa Gillespie, associate professor of Russian Language and Literature at Notre Dame, is visibly moved by the collection. “The materiality of the items speaks volumes. The sloping handwriting in brown ink in a letter from a young man to a worried, doting aunt; the pages upon pages of tiny writing tied with a ribbon. . . . The archive not only restores the particularity of a culture, a family and certain individual souls in that family to life, but it also serves as a spiritual stimulus, awakening us to the compromises we have made in our present moment, in which everything is ephemeral, discardable, recyclable.

“That we at Notre Dame now have access to this astounding collection which brings the past so vibrantly alive,” Gillespie adds, “is both improbable and fabulous.”

And significant, scholars add, to the writing of history. Released from prison in 1917, Tsereteli went on to become a central figure in the February Revolution. An effective orator, he constantly advocated cooperation between the soviet workers’ councils and the Provisional Government. The archive shows that the Petrograd Soviet, for example, accepted his revisions to their official declarations in toto. He eventually served in the Provisional Government as Minister of the Interior and left Petrograd for Georgia mere days before the Bolshevik putsch. Careful in more ways than one, Rusudana kept his official pass to a state conference that summer but erased his name. Active in Georgian politics before it fell to the USSR, Tsereteli spent the rest of his life in exile in Paris and New York, where he died.

The figure of Rusudana Nikoladze is perhaps the most fascinating discovery of all. From a prominent family deeply engaged in public affairs, she emerges as its most fully rounded character. Both a participant in and observer of public affairs (she kept two parallel diaries, one “personal,” one “political”), Rusudana found her role as a chronicler easy and natural. Her father, Niko Nikoladze, the mayor, would write letters to her sister, Tamara, when Tamara was just 16; he would ask her no questions and give no paternal advice but rather brief her on what he was about to say to the governor during a workers’ strike. She and Rusudana knew from an early age that theirs was a public family.

The sisters were not provincial, either. A prolific writer and international traveler, their father had met and corresponded with the likes of Léon Gambetta and Léon Blum (prime ministers of France) and Karl Marx (a personal friend). Niko was the first Georgian to earn a doctorate at a European university. Rusudana, his eldest daughter, was probably his intellectual equal, and her husband Mikhail’s as well. In her, and any, generation, she was remarkable.

Her personal diaries are distillations of the family’s public and private lives as politicians, historians, mathematicians and scientists. “And she was an incredible writer!” exclaims Natasha Lyandres, who has been combing through the diaries that span 30 years of modern Russian history. “To think, she was almost 100 years old when she died, active until the end.”

Convinced of the broad nature and implications of what he had seen only in part, Lyandres returned to Notre Dame and librarian Louis Jordan. The two again met with ND’s research vice president, Jeff Kantor, who was enthusiastic. In July of 2006, with full funding available, Lyandres started calling Zinaida, ready to negotiate for the rest of the collection.

But there was no answer. He tried to reach her all summer and felt the opportunity slipping away. Finally, in September, Zinaida answered. She had been sick. Negotiations began. The archive was acquired in installments. The first few were made without incident, but in August 2008, before all the papers had been delivered, Georgia was again at war and in turmoil. At one point, Russian tanks were within 30 miles of Zinaida’s apartment. “We all held our breath,” says Jordan. Fifteen months later, after long silences, the final installment arrived.

Lyandres remembers the fragility of the process. “It was very difficult. Sometimes Zinaida was in poor health, and she wanted to bring everything herself. We had to have alternatives, so we looked for alumni who would be able to help with transportation.”

In the end, Zinaida insisted on paying her own way and brought the collection to the Hesburgh Library bit by bit. Jim McAdams of the Nanovic Institute was particularly struck by the appearance of Zinaida behind a desk in the library. With a box to her left and a stack of folders to her right, she examined each piece in detail. “Her memory was phenomenal,” says Natasha.

Zinaida came three times, each time with suitcases carefully stuffed with papers and books. On a separate occasion, her daughter and son-in-law arrived with multiple suitcases containing more than Zinaida had carried on her previous three trips. The staff in Special Collections shook their heads in wonder: five thousand, eight thousand, ten thousand items and counting, all in plastic bags packed in ordinary luggage. The scale of the transfer was astonishing.

During her last visit, Zinaida said there was nothing left in the family apartment. That was it.

Her exact whereabouts are unknown.

History in Hand

Estimated at 100,000 leaves of paper, equal to 12 linear feet of materials, the Polievktov-Nikoladze Family Papers archive is by far the largest and most significant collection in modern European history at Notre Dame. And it is one of the most important and extensive private collection of papers on modern Russia in the United States. Louis Jordan can barely contain his delight with the find. “It is unprecedented to come across such a complete and extensive family archive whose members included so many prominent public figures, writers, politicians, scientists and artists. It is quite obvious that the Polievktov-Nikoladze Family Papers are of immense scholarly significance. Moreover, they have never been available to researchers. No archival repository in the United States holds a comparable collection in terms of its scope, chronological and thematic consistency.”

McAdams has been hosting visiting scholars from Europe since 2002. He is thrilled that “serious scholars of the period will now have to visit Notre Dame if they want to write about the revolution authoritatively.”

Such research and achievement is in its first stages. Lyandres has a book forthcoming from Oxford University Press on the subject, The Fall of Tsarism: Untold Stories of the February 1917 Revolution, due out in February. Oxford professor of Russian history Robert Service, who is digesting its implications, writes that Lyandres “has found important new sources and shows how they can be used to re-interpret the behavior of leading figures . . . [it is] an outstanding contribution to early twentieth-century Russian history.”

Lyandres doesn’t like the spotlight. He took the first crack at the historical commission’s interviews, but knows soberly and well how much there is yet to do with the entire collection. All the documents, which are so many and so various, need to be catalogued, described and digitized. It’s an enormous project that will take years. The goal is eventually to put it all online, but “to do it right,” says Lyandres. In the meantime, he would like to publicize the existence of the collection to as many scholarly groups as possible.

Another, more immediate priority exists, says Lyandres: to recruit graduate students at Notre Dame to work on the archive itself. This would be a major boost to their careers in modern European history at a time when jobs in the humanities are scarce. The Nanovic Institute has begun to support graduate research in this area. One of its Tobin Fellows, Maria Rogacheva, is writing a dissertation on Soviet scientist communities to which no historian has ever had access.

Notre Dame students and visitors were able to see highlights of the collection through an autumn semester exhibit at the Hesburgh Library. Designed by Notre Dame bibliographer Natasha Lyandres, with the assistance of the staff in Special Collections, the exhibit contained examples of Polievktov’s interviews, Tsereteli’s prison papers, Rusudana’s diaries and much more.

Lyandres surveys the implications of his find with satisfaction. “It’s a real coup. From nothing, our visibility changes overnight. We become a major player in Russian history.”

He and his graduate students in history now have ambitions to turn Notre Dame into the major North American repository of primary sources dealing with new Europe, more specifically, in the post-Soviet space.

What’s next?

Lyandres looks out the door and hoists his satchel confidently. “We have a preliminary agreement with some Ukrainians.”

A.P. Monta is the associate director of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies at Notre Dame. The “From St. Petersburg to Notre Dame: The Miraculous Journey of the Polievktov-Nikoladze Family Papers through a Century of War and Revolution” exhibition was on display in the Hesburgh Library during the autumn semester. Visit the digital exhibit at polievktov.library.nd.edu.