The year is 1951. The South American nation of Ecuador is hurting, having lost land and pride in a short war with Peru, the latest clash in a border dispute without end. Government leaders hope to salve the nation’s wounds with their vision of a united Ecuador and an ethnically blended national culture. They commission Oswaldo Guayasamín, a 32-year-old Ecuadorian Picasso emerging as the nation’s leading painter and sculptor. Paint us a picture of Ecuador, they implore him. Make us whole.

Guayasamín accepts the challenge but not the invitation to the propaganda team. In time he produces Huacayñán — a Quechua word meaning “the way of tears.” It is a collection of 103 paintings and a mural depicting life, customs, joys and travails among Ecuador’s Indians, blacks and mestizos, those of mixed ancestry.

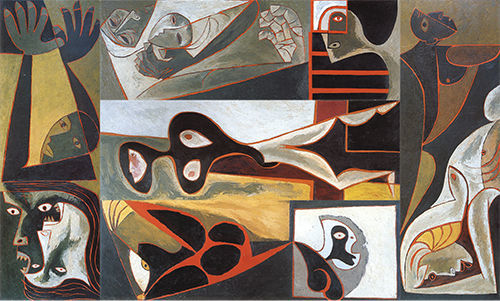

The centerpiece, Ecuador, painted in 1952, is a movable mural in five panels of equal size. Guayasamín displays it in a dozen different configurations during the 1950s, always with the panels hung vertically to form a collective rectangle. A world-class artist but not — as later admirers will discover — a thorough mathematician, he calculates 150 possible gallery arrangements.

One hundred and fifty Ecuadors, not one. The number matters far less than what it represents, a spirited statement of cultural depth and complexity in defiance of a single, state-concocted national identity.

Before he died in 1999, Guayasamín, who saw painting as a form of prayer, had an international following. He had expressed the sadness, rage and eventual tenderness of his own soul through his tireless effort to honor his people. His Capilla del Hombre, or Chapel of Man, houses the essential collection of his work in Quito, Ecuador’s capital, including the powerful, five-panel mural.

Ironically, at one point the mural was framed behind glass, and it lost some of that power. Its presentation became static to the thousands who visit the Capilla each year.

Perhaps just as ironically, Guayasamín’s museum is today a national showpiece, an icon of the dignity of Andean indigenous heritage and Latin America’s social and economic realities. “Guayasamín is, without a doubt, the most important Ecuadorian artist of the 20th century,” says Carla Portalanza, the cultural attaché to the Embassy of Ecuador in Washington, D.C.

Now, none of this would have anything to do with Notre Dame without the research of Carlos Jáuregui, associate professor of Latin American literature and anthropology. The questions he asked in his project, “Ecuador Unframed: Dynamic Art and Radical Democracy in a Mural by Oswaldo Guayasamín,” include what seems like a straightforward mathematical one: How many arrangements of the five panels could there be?

The answer, according to ND assistant professor of math Andrei Jorza, is 30,720.

Thirty thousand seven hundred and twenty murals. That assumes you stick to a rectangular arrangement of Ecuador’s panels and exhaust every configuration of panel order and rotation, both horizontal and vertical. But why stop there? Lose the rectangular fixation, and the possibilities for viewing the mural are infinite.

The artist would almost no doubt have been delighted by this mathematical revelation.

“The art that was to ‘represent the nation’ today represents nothing but unresolved contradictions,” Jáuregui wrote in a short essay about the project. The mural helps viewers reject the notion of politics as a “rosy resolution of conflicts,” he argues, and to see governing instead as the difficult art of acknowledging and negotiating them.

At any rate, this boundless multiplicity inspired Tatiana Botero, an ND Spanish language instructor and Jáuregui’s wife, to introduce Guayasamín’s heartfelt provocation to the campus community. Not the original mural, understand. That remains trapped behind glass in Quito, for fear that exposing the oils to fresh air for the first time in decades would damage it.

Instead, high-resolution scans of each panel were transferred onto new canvases. With the help of fellow Spanish instructors Elena Mangione-Lora ’98M.A., Rachel Rivers Parroquín and Andrea Topash-Ríos ’95, ’96M.A. and the support of 14 campus and community partners, Botero hatched a plan for a gallery exhibit that ran for two months in autumn 2014 at the Notre Dame Center for Arts and Culture on South Bend’s west side.

The exhibit, Art in Motion/Guayasamín’s Ecuador Unframed, included gallery talks and short videos of Carlos Jáuregui’s graduate students explaining the artist and his work. They created an iPad app that allows visitors to create their own Ecuadors by moving digital panels around a touchscreen. They also invited local teachers to create lesson plans. The result: Thirteen ideas for teaching poetry, language studies in Spanish and English, history, art and design.

And, math. Laura and Andrew Garvey of South Bend’s Good Shepherd Montessori School contributed “Oswaldo Guayasamín — Permutations of Identity,” through which junior high students learn how to verify Jorza’s calculation.

Those lessons are traveling with Art in Motion to university-based exhibits in Tennessee, Kentucky, Massachusetts and Switzerland. And just like that, one scholar’s curiosity about an often overlooked masterpiece became a multifaceted learning opportunity for thousands of people.

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine.