Matt Cashore '94

Matt Cashore '94

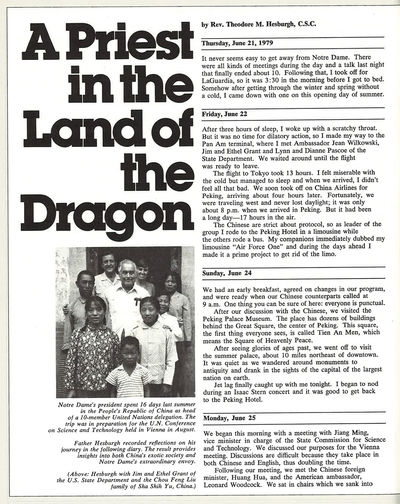

Editor’s Note: Provost Thomas Burish's visit to China this week marks 40 years of Notre Dame's involvement in the country, beginning with Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh's 1979 journey that he chronicled in a journal Notre Dame Magazine excerpted that year. In the fall of 1981, Ken Woodward, then the religion editor at Newsweek, joined a delegation from a dozen American Catholic colleges and universities on a three-week visit to China. The story below is the second of Woodward’s two reports on what he encountered there.

It was Sunday, the Feast of All Saints. From the shadows at the rear of Nanjing’s Cathedral of Immaculate Conception, a group of American Catholics moved self-consciously into the pews, knelt and blessed themselves.

Everything around us looked familiar. On either wall, a very Western Christ proceeded station by station along the way of the cross. The altar, festooned with fresh flowers, was illuminated by arcs of candlelight. Overhead, streamers of red, blue, yellow and rose formed a gala canopy for statues of Jesus and Mary.

Around us in the pews a dozen women, most of them old, chanted together in Chinese. The language was strange but the cadence was familiar: It was the rosary, recited as I had heard it said many times in my youth by women come early for Mass.

For 10 days we had been traveling through China — two bishops, ten priests, five nuns and three laymen — celebrating Mass daily in hotel rooms and feeling in those moments rather like a sect huddled against a sea of nonbelievers. Now we were among our own kind: Chinese Catholics who had endured enormous hardships to preserve their faith. Spiritually, at least, we felt at home.

The celebrant appeared. Adorned with miter and shepherd’s crook, the aged bishop of Nanjing strode down the center aisle, raining holy water left and right. When Mass began, he genuflected, his back to us, and whispered audibly: “Introibo ad altare dei. . . .” The acolytes bent low in response: “Ad Deum qui laetificat. . . .” The Chinese accent could not hide the Latin phrases that I had learned as a schoolboy in Ohio. It was the Mass as we all had learned it — Latin, Tridentine, full of prayers that now teased the memory. “I’ve forgotten half of them,” a bishop acknowledged in my ear. So, to my surprise, had I.

When the moment arrived for Holy Communion, word passed among our group: The two American bishops had decreed that no one was to receive the Eucharist. Although the Chinese bishop had been validly ordained, his Mass was illicit in the eyes of canon law; he was a member of the government-sponsored Catholic Patriotic Association and as such no longer in communion with the Pope. So we stayed put, observers at Christ’s banquet, while some 70 Chinese queued up in the aisles. Even the men, I noticed, clasped their hands reverently, fingertips to fingertips, in the fashion I had long given up trying to teach my children.

After reciting the last gospel, the bishop dressed for benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, which he held aloft like some ancient talisman of the gods. Incense drifted heavily over the pews. On my right, an organist began the Tantum Ergo, a favorite hymn of mine which, since the liturgical reforms of Vatican II, I had been able to sing full blast only in the shower. I joined my voice to those around me. I was an alien, but among brothers.

Chinese Christians find themselves in unique and difficult circumstances. That they exist at all after the terrible persecution of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) is testimony to their great courage and faith.

But unlike the Christians of Eastern Europe, who have also endured long years of suffering at the hands of Communist governments, the Christians of China are a tiny minority (less than one percent of a population nearing one billion) in a country where Christianity has always been suspect as an alien ideology.

What these survivors, both Catholic and Protestant, must do is to create something that has never existed: a thoroughly Chinese Christianity with its own mode of understanding and living the gospel. Moreover, they must do it without the aid or support of outside Christians, and within the parameters established by the government. This was the message we heard from officials of the People’s Republic of China and from the nation’s Christian leaders themselves.

The goal of establishing an indigenous church is difficult. The Vatican does not want to encourage the schismatic Catholic Patriotic Association, but neither does it want to lose all contact with the only Catholic organization permitted by the Beijing government. To make matters worse, many Chinese Catholics still regard the Pope as the head of the church and refuse to cooperate with the C.P.A., which denies papal jurisdiction in China. The Diocese of Shanghai, for instance, claims 100,000 faithful, yet Bishop Jiang Jiashue, who is also head of the C.P.A.-controlled Catholic Bishops Conference, acknowledges that only 40 priests and laymen from the Shanghai diocese belong to the C.P.A.

The delicacy of the Catholics’ situation can be measured by the recent furor over Jesuit Dominic Deng, who was elected bishop of Canton in 1980 by the Catholics of that diocese and in accordance with government and C.P.A. regulations. Significantly, Deng, now 73, had only recently been released from prison after serving 22 years as an “enemy of the people” for refusing to break with the papacy. His election reportedly shocked the other Chinese bishops, but it was accepted. Subsequently, Deng was permitted to go to Hong Kong for medical treatment. In that period, he made two trips to Rome during which the Pope announced Deng’s appointment as archbishop of Canton. The papal appointment was widely interpreted outside China as a gesture of reconciliation toward the C.P.A. But inside China, the Pope’s move was sharply denounced as Vatican interference in the country’s internal affairs. Deng was dismissed as a “running dog of the Vatican” and the Beijing government has since refused to allow him to return to the diocese.

In various visits with C.P.A. bishops, we were told that membership in their organization, which is open to both clergy and laity, is voluntary. Yet coercion is evident. During our stay in Shanghai, for example, Jesuits in our delegation met with the Rev. Vincent Chu, S.J., who had been imprisoned for years and who still refuses to join the C.P.A. A month after that brief meeting, Father Chu and 16 other Catholics were arrested and imprisoned again, reportedly for making contact with foreigners.

Nonetheless, the bishops and clergy of the C.P.A. are obviously Catholic. The major difference is that they do not — indeed, cannot — accept any direction from Rome. Yet the irony is that they are in many ways more Roman than the Romans. The Mass they say and the breviary they read are in Latin; the collars around their necks are distinctly Roman. In conversation, they fingered pectoral crosses and proffered episcopal rings. They even questioned the traditionalism of Catholicism in the United States. “Tell me,” the C.P.A. bishop of Beijing asked at one point, “do they still teach Saint Thomas Aquinas in American seminaries?”

Protestants have found it easier than Catholics to develop an autonomous Chinese church. Chinese Protestants were never tied to their mother churches overseas like Catholics were tied to Rome. Moreover, Chinese Protestants were, on the whole, less inclined than Catholics to resist Communism as an inherently evil force. Even so, Protestants have their own roll call of martyrs and their own “silent church” which would rather meet clandestinely in homes than identify with the government-approved “Three Self Movement” (self-government, self-support and self-propagandizing) which oversees official Protestant church life.

One price paid for Protestant survival has been the abandonment of denominational distinctions. At the time of the Communist victory in 1949, about 270 different denominations, from Anglican to Jehovah’s Witnesses, were operating in China. Today, the government claims that, for practical reasons, it cannot open enough churches to allow each congregation to go its own denominational way. Thus Protestant church life today reflects a “post-denominational” commonality in Sunday services (which are held on Saturdays as well to accommodate Adventists and other Sabbatarians.)

Home meetings and other rituals, however, retain old denominational accents: Baptisms, for example, are performed by sprinkling, pouring or immersion. “We teach one God, one baptism and one Bible,” explained the vice president of the Protestants’ Union Seminary in Nanjing, which reopened last year. “We regard ‘denomination’ as a historical term only.”

Nonetheless, Baptists and other evangelicals have determined the Chinese Protestant ethos. “Christians,” the seminary vice president informed me, frowning ever so slightly at my pipe, “do not smoke, drink or dance.”

Chinese Protestants also have their problems with fellow Christians overseas. Shortly before we arrived in the country, the Western press carried a story of an evangelical group which boasted of landing a million Chinese-language Bibles on a beach near Shantou. In Nanjing, officials of the Three Self Movement confirmed that the smuggling had taken place. But they insisted that most of the Bibles washed out to sea while the militia seized the rest. Moreover, they regarded the entire episode as reflecting discredit on the Bible and themselves. “We are printing our own Bibles as fast as the government can supply the paper,” the church official said proudly. By the end of 1982 they have to have nearly 300,000 in print.

It would be hard to overemphasize what possession of a Bible, a rosary or a prayer book means to Chinese Christians. In a suburb of Nanjing, I visited a family in which the mother and her mother-in-law both were Christians. The younger woman brought out an old Bible which she had managed to hide from the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. She showed me her favorite Psalms, in English, then handed me a hymnal printed by the British Bible Society in Shanghai in 1926. She began to sing, tears forming in her eyes: “For me, for me, Jesus came down from heaven for me.” It was, she said, her favorite hymn.

The visitor to modern China can only imagine from the meager evidence at hand what Chinese Christianity was like before the Communist revolution. Though never more than two percent of the population, Christians operated thousands of schools, universities, medical centers and the like. In the 1930s, 35 per cent of the Chinese elite had receive a Christian education. Ninety per cent of all nurses were Christian, and 70 per cent of all hospitals were run by mission societies. Groups like the YWCA among Protestants and the Legion of Mary among Catholics held the allegiance of millions of Chinese youths. A native clergy was growing up alongside the missionaries, though the latter — as the Communists have repeatedly pointed out — were not proportionally represented among the hierarchy, especially the Catholic episcopate.

Today, these structures have all disappeared. Since 1964, it has been unlawful for anyone, including parents, to teach religion to children under the age of 18, though obviously the law is difficult to enforce. What’s more, China is a society where everyone is expected to work. As a result, parents seldom attend church services together except on those rare national religious holidays (four for Catholics, two for Protestants) when both are exempted from work.

In sum, after 30 years of Communist rule, the Christian churches of China are poor, weak and aging. Although the Chinese constitution guarantees freedom of religion as well as of atheism, only atheists are permitted to propagate their views.

Read Father Hesburgh’s diary of his 1979 visit to China.

Read Father Hesburgh’s diary of his 1979 visit to China.

In the pulpit, however, Christian clergy can and do criticize atheism. But the line Christians must tread is narrow. For instance, the Catholic clergy must support the country’s draconian birth-control laws which limit couples to a single child. In short, Christians are tolerated so long as they manifest support for whatever the government deems necessary for socialist progress. As a practical matter, this means that they must demonstrate, in the words of Bishop Jiashue, that “love of country and love of religion are not contradictory.”

The suspicion that Christianity is incompatible with Chinese patriotism was not invented by the Communists. On the contrary, Mao’s insistence that Chinese Christians cut their ties to foreigners echoes mandates from many emperors who preceded him. In part it reflects a Chinese xenophobia that predates Christianity itself; China, after all, was already an ancient and aloof civilization the day Jesus was born. Suspicion of Christianity also reflects a record of missionary mistakes and failures — of repeated foreign transplants that never took. It is against this history that the present state of the Chinese church must be understood.

China’s first known Christian missionaries were Nestorians who came and then vanished in the 7th and 8th centuries. They were followed by the Franciscans in the 13th century, but they too failed to establish a permanent foothold.

The Jesuits arrived at the end of the 16th century and were more successful for two important reasons. First, Father Matteo Ricci and his fellow Jesuits introduced aspects of Western science which Chinese intellectuals welcomed and respected. Second, the Jesuits showed great respect for the integrity of Chinese culture. In what has become known as the great “Chinese Rites” controversy, the Jesuits urged Rome to allow them to adapt Christianity to Chinese language and culture. The Dominicans and Franciscans opposed such innovations. The Vatican waffled, then condemned the use of the vernacular by missionaries in China. In retaliation, Emperor K’ang Hsi, who first issued an edict of freedom for Christianity, ordered missionaries deported for their failure to respect the rites and customs of the Chinese people. Rome is still paying dearly for this mistake.

By the 19th century, China’s imperial government was firmly set against Christianity and what successive emperors regarded as the missionaries’ intrusive threats to their own social system and values. But by 1858, economic coercion achieved what all the missionaries’ prayers and blood had failed to achieve. In a series of unequal treaties with France, Britain, Prussia and the United States, China was forced to protect the freedom of Christians in her land and to restore confiscated property to the missions.

These treaties had a double effect on Chinese Christianity.

On the one hand, they allowed for the subsequent flowering of Christian mission schools, universities, hospitals and churches. In 1911, the last Chinese emperor was overthrown by the followers of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, a Protestant trained in missionary schools. Thereafter, Christian missionary enterprises flourished as they never had before.

On the other hand, Christianity became permanently identified with Western colonialism and economic imperialism. In the Nationalistic Period (1926-1949), the elites under Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-shek — both Christians — leaned heavily on missionary institutions and Christian supporters abroad. Among the most important was Henry R. Luce, a son of missionaries to China, whose editorial championing of Chiang Kai-shek in Time and Life was influential in shaping American foreign policy.

Little wonder, then, that when Mao’s “Liberation” movement drove Chiang to Taiwan, mainland Chinese readily accepted the axiom: “One more Christian, one less Chinese.”

With the Communist victory in 1949, religion was declared one of the “four thick ropes” binding China’s peasants to a feudal past. This was perhaps truer or Buddhism, Islam, Taoism and China’s various folk religions than it was of Christianity. At that point China had an estimated 4.7 million Christians, 72 per cent of them Catholic. Most were urban. The particular crimes of Christians, in the Communists’ view, were their prominent role in the defeated Nationalist regime and their ties to overseas “imperialists.” China’s new rules were especially scornful of Catholicism, since only 20 of the 137 bishops in China were natives.

The message to Christians was clear: They would be allowed to practice their religion only if they freed themselves from alleged “foreign domination” and wholeheartedly supported the Communists’ Four Modernizations — agriculture, industry, defense, and science and technology. The papal nuncio responded by joining Archbishop Yu Pin of Beijing in fleeing with the Nationalists to Taiwan.

On the advice of Premier Zhou Enlai, the Protestants formed the Three Self Movement in 1951, but the Catholics balked at following suit, even though Zhou accepted the fact that Catholics require ties with the Pope. In 1952, the last of the Western missionaries were expelled or imprisoned.

Four years later, the Catholic Patriotic Association was formed to handle relations between the church and the Religious Affairs Bureau, which oversees religious activities for the Chinese government. Several new bishops were elected to the Chinese episcopate, and although their names were submitted to Rome for approval prior to public consecration, Pope Pius XII condemned the C.P.A. as schismatic. Since then, there has been no official contact between the Vatican and the church or the government of China.

Initially, Mao’s attitude toward religion was a mixture of cynicism and pragmatism. As a Marxist, he expected religious enthusiasm to fade as material progress and scientific education developed. But he also wanted a “united front” in China and so tolerated religion, especially the huge Moslem and Buddhist populations in China’s western provinces.

During the Cultural Revolution, however, Mao unleashed the frenzied Red Guard, who dismantled the Religious Affairs Bureau, burned Bibles, converted churches into warehouses and smashed priceless art. Worship and theological education were banned; clergy and laity were tortured, imprisoned and killed. Christians were driven into a catacomb-like existence. For several years, an ominous silence fell over the Chinese church.

With the death of Mao and the repudiation of the so-called Gang of Four, the government under the more moderate Deng Xiaoping has reinstituted the concept of the united front. Churches have been opened in showplace cities such as Beijing, Nanjing, Canton and Shanghai — more as a means of improving relations with the West, some skeptics believe, than of facilitating worship. Christians still cannot belong to the Communist Party — both sides agree on that — but they do have representation on other government bodies and can hold local civic posts. Just what is acceptable behavior for Christians is up to the government to decide.

At each of our meetings with Chinese Christians, we were welcomed with warmth — and wariness. Even officials of the C.P.A. were circumspect.

In Beijing, we took tea with Bishop Michael Fu. The bishop, chuckling and puffing on Chinese cigarettes, told us how he spent his time during the Cultural Revolution. “I was sent to the country to cultivate trees,” he said. “I became an expert at planting peach and apple trees. Now, we have fruit trees in our churchyard. But since religious freedom has returned we don’t plant trees anymore. We tend sheep.”

At 52, Fu is one of China’s younger Catholic bishops. His conversation focused on church issues. On Sundays, he reported, about 2,000 attend Mass in Beijing’s two Catholic churches. About 8,000 turn out on Christmas and Easter. “We are only a little flock of Jesus in Beijing,” he insisted. “We have about a dozen priests and 30 sisters. Most of the sisters are very old; some teach, some are nurses. Our main emphasis right now is on training new priests.”

The picture was much the same in Shanghai. That diocese includes 100,000 Catholics but only 40 priests to care for them, and many of the priests are so old that they need care themselves.

Sitting under a faded picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Bishop Jiashue, at 90, proved to be alert and surprisingly well informed about the church in the United States. When he learned that I was from Notre Dame, for example, he asked how federal cuts in student loan programs would affect the University. In China, he observed, the Catholic Church must depend upon state funds for its only seminary, due to open in Beijing this fall. “The money can’t come from Chinese Catholics,” he said. “They are too poor.”

The American bishops in our group, recognizing a pitch when they heard one, asked whether the Chinese would accept donations from outsiders. “We have not considered that,” Bishop Jianshue replied. “It involves political and other factors. But if we display the spirit of Jesus fully, if we behave ourselves . . . perhaps someday we will be able to do it.”

Nonetheless, the bishops did feel that they could accept books and training manuals for priests — so long as they were in Latin and were published prior to Vatican II. The Chinese, it is evident, want nothing to do with the council and its reforms. They are busy reviving Catholicism as they knew it before the council and the revolution, the only Catholicism they know.

When it comes to training new clergy, the Protestants are more advanced than the Catholics. When Union Seminary reopened last year in Nanjing, 51 students — 22 of them women — were selected from among 300 applicants. About a third of the students come from non-Christian families. Their average age is 25; most already have had three years of university education. The seminary is run by the Chinese Christian Council and is supported in part by rents the government allows the council to collect on former missionary schools.

About 90 per cent of the seminary’s books were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Most of the rest are in English. Among other volumes in the grey-stone library, I found books by Hans Kung and Edward Schillebeeckx and the dogmatics of Karl Barth.

“Most Chinese can experience what we mean when we say, ‘Christ died for me,’” said the seminary’s wiry dean of studies. “Our main problem is to have Chinese accept our ideas about God, resurrection and atonement. We have to interpret these ideas within Chinese culture.”

For the moment, therefore, the curriculum is limited to basic courses in the Bible, history, hermeneutics and pastoral theology. With these, students can go into homes to teach and care for families. They can also preach. “We would like to also offer courses in biblical criticism, as we did in the past, but we can’t just yet,” said the dean. “The students are not yet sophisticated enough for that.”

Interestingly, the seminary also operates a Center for Christian Studies where scholars translate books, write articles for a forthcoming Chinese encyclopedia of world religions and lecture to non-Christian students at nearby Nanjing University. Last year nearly 1,000 students turned up to listen to lectures on the biblical background to Marxist and other liberation movements. “We like to emphasize that Marxism is Western too,” a professor pointed out.

Chinese Christians are once again free to publish their own materials, most of a pastoral nature. On the other hand, Marxist academics have also developed a significant, if methodologically uniform, interest in religion.

At the Institute of World Religions, one of 31 institutes within the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 90 researchers and other staffers are preparing doctoral candidates who will teach about religions in the nation’s universities. Their approach is strictly Marxist. As one institute official explained during a morning-long meeting, “We look at religion as it has originated, developed and is conditioned by society. We do not try to pass value judgments but to explain religion’s role in various societies.”

Chinese academics, naturally, are particularly interested in the religions that have persisted within their own borders. The institute is preparing new translations of the Koran and the Dead Sea Scrolls, plus a history of Islam in northwest China. They are also using film and sound to record Chinese folk religious practices. “And we have a rich collection of Sanskrit scripture in Lhasa,” one official remarked. What he didn’t say, of course, is that this rich collection originally belonged to Buddhist monks in Tibet before the Chinese army overran that ancient Himalayan kingdom.

From conversations with members of the institute, it seemed to me that the Chinese interest in Christianity is triggered mainly by two considerations. They are intrigued by the fact that Christianity is the major religion of those societies, particularly the United States, which have the most advanced science and technology. They are also keenly impressed by the fact that religions, especially Islam and Christianity, have generated what the Chinese ideological journal Red Flag called “a formidable force” in countering Soviet-style hegemony.

Toward the close of our three-week visit, a member of our delegation, Father David Tracy, a professor at the University of Chicago Divinity School and an occasional lecturer at Notre Dame, delivered a paper on the role of theological studies in the Western secular university. Tracy was the second Catholic theologian to address the institute (the first, last year, was Hans Kung). In his paper, Tracy stressed the critical function of theology vis-à-vis secular assumptions and insisted that no one can adequately understand any culture by eliminating the religious classics that culture has produced.

Afterwards, the institute’s impressive leader, Professor Zhao Fu-san, questioned Tracy on Kung’s controversies with the Vatican and on the significance of Vatican II. Tracy defended Kung, with minor qualifications, and declared that in his judgment the council was the most important religious event of the 20th century.

The two American bishops added that the council stressed the importance of local churches within Catholicism and regretted the absence of any contributions to the council from the church of China. Their points were judiciously put — and were received with polite silence. As an institute official later explained, its scholars have no influence on government policies regarding religion.

I came away from China with a bundle of conflicting conclusions and emotions about the future of Christianity in that ancient, sprawling, sad yet wonderful country.

It is obvious that the Chinese Church, Catholic and Protestant, is badly split between those who refuse to cooperate with the government-sanctioned ecclesiastical entities and those who wish to accommodate them. Both kinds of Christians deserve our praise. The Chinese church will continue to produce anonymous martyrs for the faith. Still, the government must be accommodated if Christianity is to survive.

The Vatican can play a decisive role in determining the future of Chinese Catholicism—just as it has played a decisive, though not always benign, role in its past. After all, the Vatican is the home of Realpolitik; it has shown in its dealings with Communist governments in Eastern Europe that it is willing to make accommodations. I suspect that accommodation with the Chinese insistence on ecclesiastical autonomy is possible without betraying principles on either side. Indeed, I cannot help but suspect that the C.P.R. may one day decide that it is to its benefit to reestablish diplomatic ties with the Holy See and to allow the Pope the kind of spiritual jurisdiction over Chinese Catholics that Zhou was once willing to accept. None of this, however, detracts from the fact that the Chinese must develop an indigenous Christianity if the faith is not to disappear once again.

There is a cultural problem as well. China today is a work society. In such a society, religion can at best be tolerated because it serves no “useful” purpose. It is significant that only nine per cent of the education which the Chinese prize so much is devoted to the humanities and social sciences. In short, the notion of study for its own sake — the asking of basic human questions — is not encouraged in China. Political indoctrination is still supposed to answer all such questions.

Chinese Christians have suffered much. But their faith at least gives them a purpose, a reason to praise the day and to look forward to tomorrow. Atheism, especially when it becomes official ideology, cannot do that.

Such is the concern over religion’s potential attraction for Chinese youth that the official People’s Daily recently admonished the nation’s 39 million Communist Party members to disregard the government’s new climate of religious tolerance and to press the propagation of atheism. Given the powerless state of Chinese Christianity, this in itself is a confession of weakness.

If there is to be a Chinese Christianity — and history offers no proof that there must be — it will have to emerge out of the crucible of the Chinese experience. Christians outside China can only wait and pray and vindicate by their actions what Christians in America have learned from their own experience: that love of God and of country are not mutually contradictory.

Ken Woodward was religion editor at Newsweek for 38 years, retiring in 2002. He is the author of several books, including most recently Getting Religion: Faith, Culture, and Politics from the Age of Eisenhower to the Ascent of Trump.