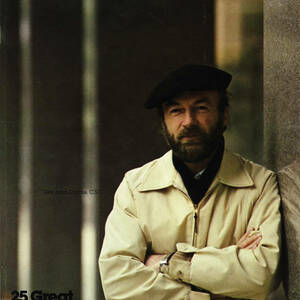

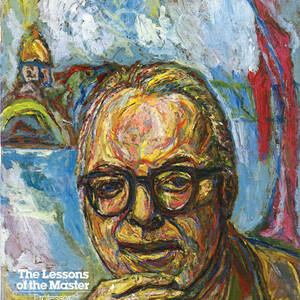

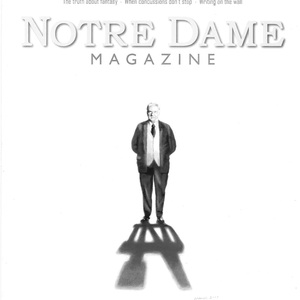

In September 1985, Notre Dame’s president, Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, spoke to a gathering of editors from college and university magazines. The editor of the University of Iowa’s alumni magazine took notes. She typed them up and sent them to Walt Collins ’51, then the editor of Notre Dame Magazine. Carol Harker’s weathered, one-page, singled-spaced sheet is taped to a wall in the magazine’s offices in Grace Hall.

Here is a sampling:

“An alumni magazine,” Hesburgh is quoted as saying, “should be critical at times, praising at times, and it should be honest.”

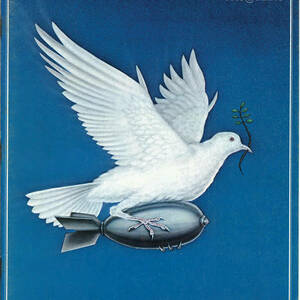

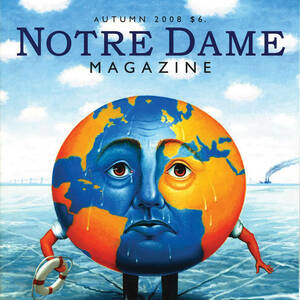

“Write about national and international problems. Even better, get people who are known and respected to write about these issues. There are a lot of problems that, handled with a little bit of imagination, would be of interest to alumni — the nuclear problem, how do we deal with the Russians, race in America.”

“The magazine should challenge readers to do some thinking.”

“Don’t be afraid to make alumni angry. At least it wakes them up to something intellectual. . . . Let your readers scream back at you. Don’t be afraid of disagreement.”

There are more Hesburgh notes from that day — that the magazine’s fundamental endeavor should be to provide continuing education to alumni and that it should not be afraid to criticize the university “fairly and honestly.” Hesburgh’s talk played well to this audience, especially when he said, “I think the editor should get a lot of elbow room.”

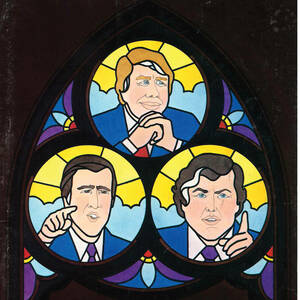

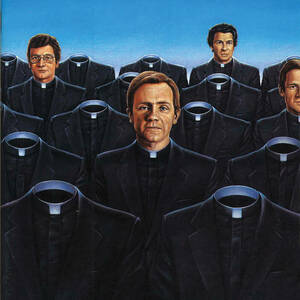

Those steering publications at other schools have often expressed envy for the kind of editorial autonomy and institutional support that Notre Dame Magazine has enjoyed since its inaugural issue 50 years ago — support that has continued throughout the 36 years since Hesburgh spoke to that assembly of editors. This unique relationship between the University and its magazine — buttressed by Hesburgh’s successors, Rev. Edward “Monk” Malloy, CSC, ’63, ’67M.A., ’69M.A. and Rev. John Jenkins, CSC, ’76, ’78M.A. — has long been an integral component in its success as a periodical widely respected in higher education and trusted and valued by its readers.

The parameters were established at the outset. Hesburgh, along with James Frick ’51, the University’s vice president for university relations, and Richard Conklin ’67M.A., Notre Dame’s chief communications officer, envisioned a publication that covered the institution with candor and clarity, told the stories of alumni and took on the most compelling issues of the day, keeping its readers informed and attentive to society’s currents and moral thickets.

The magazine was to be a print extension of Hesburgh’s vision for the place, perhaps most succinctly expressed in his “Endless Conversation” statement, in which he defined the University as “a crossroads where all the vital intellectual currents of our times meet in dialogue, where the great issues of the Church and the world today are plumbed to their depths,” and “where differences of culture and religious conviction can coexist with friendship, civility, hospitality, respect and even love.”

The magazine’s first editor, Ron Parent ’74M.A., explained: “When planning the magazine, we felt it should reflect those values and insights, those spiritual and intellectual concerns that are so much a part of the life and substance of Notre Dame. We wanted to deal squarely and honestly with the issues of our time, to address all those subjects that would interest people who feel strongly, even passionately, about Christian values and ethics.”

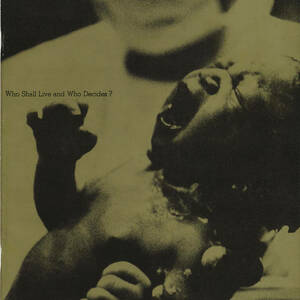

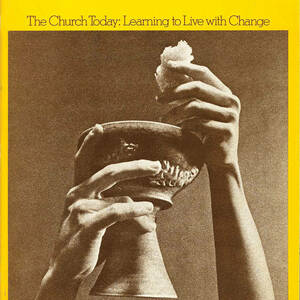

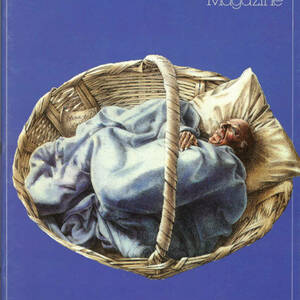

The first edition’s cover in February 1972 bore the teaser, “Who Lives and Who Decides?” Inside were stories about abortion, capital punishment and euthanasia by faculty members with differing opinions. Subsequent issues those first years would deal with science and faith, the sacrament of penance, medical ethics, death, “the good life” and a Christian’s obligation to society’s most vulnerable — along with plenty of big photos, campus news and profiles of faculty and alumni.

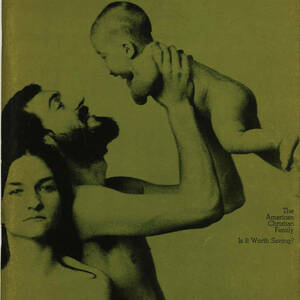

The magazine was also a product of its times — an edgy, experimental era of bold, tradition-defying attitudes. A 1973 cover asking, “The American Catholic Family: Is It Worth Saving?” carried the grainy image of a “hippie” family, apparently naked but carefully posed from the waist up, with their bare-bottomed infant held aloft.

The 1970s was indeed a time for questioning, and for hashing out the answers. American society was emerging from the tumult of the 1960s — from the Vietnam War and turbulent campus protests; from the painful cleavages of desegregation, civil rights marches and race riots; from sexual liberation and the feminist revolt; from the cultural upheavals of a disaffected generation rebelling, with everyone else bracing for an uncertain new world; and from a Church in disarray, following a Vatican council that shook the faith’s foundations with the airy promise of a spiritual renewal. There was much to write about.

In the wake of these societal disruptions, the magazine set its sights forward — often with a sense of possibility and optimism — asking where do we go from here; positing not just what’s next, but what could be next; posing dilemmas for thoughtful, questioning people of conscience. In its early days and for decades hence, the magazine has been comfortable asking uncomfortable questions and providing a place for disparate voices to sift through the answers — even when those discussions elicited discord.

The University has sometimes provided its own sources of controversy. Dick Conklin, the longtime communications sage, often called Notre Dame “the canary in the coal mine,” as a place that signaled coming societal shifts and forecasted trends soon to be faced by the Church and surrounding culture. When the magazine has reported on the place of Blacks or women on campus, focused on student drinking or LGBTQ concerns, or questioned Notre Dame’s Catholic character and changing personality, readers have spoken loudly.

The magazine staff has always understood these reactions as alumni caring deeply about their alma mater and wanting it to exemplify what they believe are its most treasured virtues. Those 151,000 alumni present a wide range of opinion about what’s best for the place.

The editors also believe that the depth of love for Notre Dame should be rewarded with stories that tell the family what really is going on here. Guided by the aims of education and journalism, the magazine staff actually enjoys the give-and-take of intellectual sparring — especially among those whose minds are informed by their hearts and souls.

Unfortunately, a healthy discourse has been hindered in recent years as battle lines have been fixed that draw complex issues into shadeless black and white and spark much squabbling and little genuine listening. Exploring questions together is much less fun when so many already have their own answers.

Of course, some issues threaten the world’s well-being and are too important to avoid, but the magazine has lately sought to deliver stories that serve to unify and pursue common ground — and the good — in a tack toward a peaceful détente among family members.

A similar adjustment of editorial approach was inspired by a discussion during one of the magazine’s weekly staff meetings a few years ago. The topic was how very seriously Notre Dame takes itself, how earnest in all regards, how unflappably humorless — because everything is serious, is important, you know. Then it occurred to the editors that the magazine was pretty serious, too, and that we should do something about that by injecting a little fun into the proceedings — for us, our readers and this “modern Gothic” institution.

So the staff fashioned a style issue — one of our all-time favorites, although dozens of letters objected to the magazine making a to-do over clothing, physical appearances and shallow materialism. “What have you done to my magazine?” the readers howled. Undeterred, the staff subsequently put together issues on food and list-making and eventually fun itself — with a coloring-book cover. A magazine with a light touch, and an occasional surprise, is a better magazine.

Perhaps the periodical’s biggest challenge in its 50-year history, though, has been the communication revolution and the perpetually changing media landscape, spurred by the technology of immediate access, the transformation of information delivery, the power of screens and social media, the demise of print. The editors knew in decades past that a quarterly magazine that didn’t adapt to these new frontiers is bound for obsolescence. So Notre Dame Magazine, still widely perceived as solely a print vehicle, ventured into the digital age some decades back. Its website, while clearly a reflection of the print publication, is fresh daily, with news, essays, photos and stories to meet readers’ “snackier” appetites, along with an active social media presence.

While the editors have adapted to society’s changing tides and temperaments, the magazine has remained true to itself, and is vigilant about those valuable constants — quality, credibility, fairness, integrity, stories that appeal to one’s conscience, that convey a sense of Notre Dame and reflect the institution’s character. These days it is not only a publication that strengthens the bonds of the Notre Dame family but also carries the University’s voice into wider national conversations on issues of real importance.

One of the constants most appreciated by the staff is the enduring support of its readers, in ways both tangible and intangible. It is truly a collective enterprise, a collaboration of countless contributions. One measure is the magazine’s voluntary subscription fund, launched in 1978 to bring color onto the magazine’s pages, pay freelancers and make a bigger magazine. Today alumni, who receive the periodical free for life, generously donate the resources that make this magazine possible, enabling us to pay the writers, photographers and artists with whom we work and to keep pace with the rising costs of paper, production and postage.

As Notre Dame Magazine marks its 50th anniversary, the world we face may feel worrisome and unsettling; things have felt shaky before. The magazine was born of a period of rapid transition and uncertainty. Now, like then, the world needs those places committed to sincere inquiry, reasonable dialogue and the faithful pursuit of truth — whether addressing our institutions, human welfare or the fate of the planet. The times call on those with sharp minds and vision and compassion to lead the conversations that will take us — all of us — to a better world. So future editions are being planned and stories assigned as we continue to translate good writing and pictures into soulful nourishment. At least that’s what we still aim to do.

Kerry Temple has been on the magazine staff since 1981 and editor since 1995.