Days from now, Ben O’Donnell, when you face a new and strange form of death, you will think back to where the fever started.

You have returned home after flying around the United States for work: Denver, Houston, and back to Minneapolis on Saturday, February 29, 2020.

Home to your wife: Deanna O’Donnell ’10Ph.D., who didn’t have a ticket to see Notre Dame play Washington when you met that football Saturday in 2004, so you forgot your ticket and walked around campus with her instead. Deanna, whom you married in 2006 in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart.

You and Deanna now have a 3-year-old daughter. Here, standing out past the old pine at the fork in your driveway, surrounded by stands of maples, your golden retriever Riley bounding through your snowy backyard — here, in the leap year to forget, your journey begins.

Check your temperature: 102 degrees. You almost pass out climbing the stairs. You text your cousin Jason: “I caught a bug, high fever. I’ve been staying away from the girls. Just trying to rest.”

Jason is your training partner and one of your closest friends. You started training with him in 2015 for the camaraderie, back when you were an out-of-shape cubicle person rediscovering his inner athlete. Doesn’t matter that you’re more fullback than triathlete — six-foot-something, two-hundred-and-something, football and baseball at Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota. On runs with Jason, you’re “gorillas in the mist,” “rhinos on the Serengeti.”

You were there when Jason completed Ironman Madison in 2015, marveling at the event’s electricity — like Notre Dame Stadium on game day. That sparked your own first sprint and Olympic triathlons in 2015 and your Lake Superior half-Ironman in 2016. Then, in 2017, with Jason guiding your transitions, you completed Ironman Madison: a 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike ride and full, 26.2-mile marathon. At the end you heard Mike Reilly, the voice of Ironman, confirm it: You, Ben O’Donnell, are an Ironman.

Now, even as you contemplate your high fever, you’re ready to do it again: Ironman Arizona, November 2020. You have a treadmill and indoor bike trainer in your basement. You had an executive physical at the Mayo Clinic two weeks ago: Clean bill of health.

But this fever. It goes on four more days. You visit Mayo again. They can’t test you for the coronavirus — you haven’t traveled to an infection hotspot — and you test negative for everything else.

March 5, March 6: Upset stomach, crushing fatigue, the first few coughs. Now your sister Dawn, a nurse at the Mayo Clinic, starts to worry. She knows you’re stubborn about taking care of yourself, and you’re barely moving, barely eating. Riley settles for walks around the house, then for no walk at all.

You resist going back to the hospital for another four days, until you relent on March 9, mostly to appease Dawn. Deanna drives you to M Health Fairview, the University of Minnesota’s hospital in Minneapolis. You wave goodbye to your daughter in the back seat, telling her, “I love you.” Into the emergency room, and then to a negative-pressure room with a glass wall.

Later, when you surface from the nightmare, you will remember this vision: You are on one side of the glass, Deanna is on the other. I love you, you sign to her. I love you, she signs back. Then she is gone. And you are alone.

The doctors suspect COVID-19, but they won’t know until the tests come back. The attending physician tells Deanna: “I’ve been here for 30 years, and I’ve never seen a chest X-ray like this in my life.”

Deanna texts Dawn: “Ben’s oxygen levels are 90 percent.” By mid afternoon: “Ben needs six liters of oxygen to stay at 90 percent.” The nurses move you to a negative-pressure room in the intensive care unit. “Ben is on a full non-rebreather oxygen mask and he’s barely holding 90.”

Dawn has seen this before and knows you’ll be intubated by morning. A nurse calls at 6 a.m.; Deanna approves the ventilator, concerned but unshaken, but your lungs are still failing. Deanna gets another phone call. And when the attending physician, Dr. Salma Shakar, starts explaining ECMO? That’s when Deanna and Dawn realize how close you are to death.

ECMO — extracorporeal membrane oxygenation — is the end-all-be-all of cardiopulmonary life support, a heart-lung bypass system that pumps the blood out of your body, infuses it with oxygen and pumps it back in. It’s the last, dire option for patients like you, whose lungs cannot summon enough oxygen to keep them alive. Only 50 percent of patients survive the procedure to start ECMO. (The University of Minnesota’s ECMO team is better than most hospitals’, Shakar says, so maybe more than 50.) You also face a 10 percent chance of a brain bleed, because ECMO requires a blood thinner to prevent clotting in the machine. ECMO may not even help: Of a few dozen ECMO COVID-19 patients in China, only one or two have survived.

Deanna starts doing the grim math: a greater than 50 percent chance Ben survives if I say yes, a zero percent chance if I say no. . . .

You lie down on a picnic table under some trees. A light drizzle falls on your face, and you cry. A wave of loneliness hits you even as the moment reverberates through your soul. After the hospital, the recovery, and two canceled races; after living apart, then reunion; after long COVID, numbness, brain fog — after all that: I can’t believe I’m here.

Surgeons insert a garden-hose-sized catheter into your neck. One tube in the catheter carries your oxygen-depleted blood — now the melancholic hue of a fresh bruise — out of your body and into the bedside machine. The machine oxygenates your blood, scrubs out the carbon dioxide, and sends it back into your body through a second tube in the catheter. ECMO, dialysis, ventilator, medications: all this just to keep you alive.

You are a harbinger and a science experiment: the first hospitalized COVID-19 patient in Minnesota and the first such patient on ECMO in the Western Hemisphere. The hospital hides your name on the records for privacy.

M Health Fairview can bring its best to your bedside. Dr. Melissa Brunsvold, a critical and acute care surgeon and head of the hospital’s ECMO program, orchestrates your care across the attending-physician rotations. Nephrology for your kidneys. Hematology for your hemoglobin. Infectious disease specialists for the novel coronavirus diagnosis. Palliative care — not for end-of-life, but to maintain the essence of who you are: Ben O’Donnell, 38, husband, brother, cousin, friend, father, Ironman.

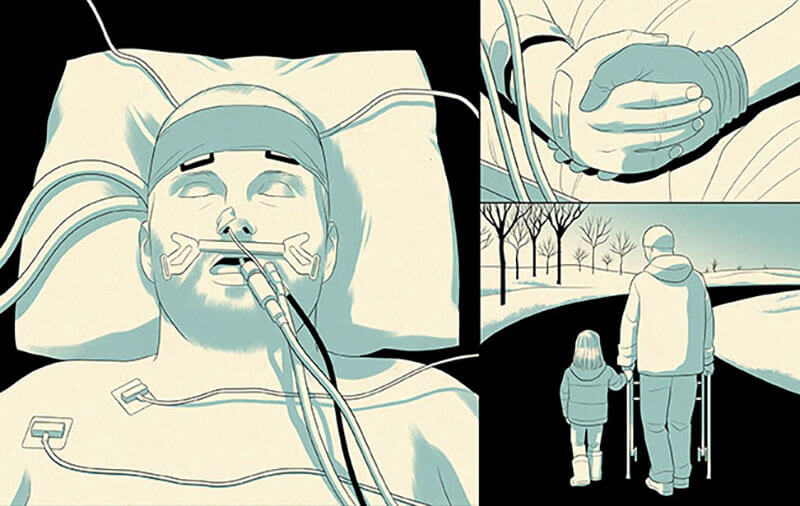

With Deanna still in quarantine, the hospital clears Dawn to visit on Friday, March 14. Anyone would be overwhelmed, but seeing this: her younger brother, now unconscious in an isolation room, spiderwebbed with IVs, hands restrained, sustained by tubes in his neck. Well.

She gowns up and goes in. Dawn frees your hands, takes one in hers, tells you she’s here. Somehow, through the haze, you squeeze her hand ever so slightly. Somehow you sign, I love you.

They bring pictures: Your daughter. Your first Ironman. Grand Teton, because Jason turns 40 this year, and to celebrate you have agreed to do the Teton Picnic in August. You plan to start at midnight, ride your bikes 20 miles, swim across Jenny Lake, summit Grand Teton (elevation 13,775 feet), and then do the whole thing in reverse.

Your family sends videos: telling you to get better, reaching for normalcy, updating you on the Vikings. In her daily visits, Dawn asks: “Do you want to see any videos?” You squeeze her hand or nod. Always Deanna and your daughter first. Then: “Jason?” A nod. “Your brother Al?” Another nod. Twice in the morning, twice in the afternoon.

You need these touchstones. Seared by nearly two weeks of fever, under sedation, your mind distorts the hospital room into vivid hallucinations. In your febrile mind, you are a captive of a human trafficking operation, held against your will. (Once, when the staff tries to put your mitts on, you slowly raise a middle finger. Dawn can only laugh. Humor, defiance: Yep, that’s Ben.)

You are unlucky, you are lucky. Not every COVID-19 patient’s wife solves the insurance while you sleep, holds a doctorate in chemistry from Notre Dame, speaks the scientific language. Not every COVID-19 patient’s sister accompanies doctors on rounds, understands what must be done to keep you alive.

The doctors notice your stratospheric levels of the antibody interleukin 6. They suspect it might signal a cytokine storm, when the immune system’s supercharged killer cells attack the body. A potential treatment, a monoclonal antibody called Tocilizumab, requires special permission. Only on Monday, March 16, do you get your first dose. We’ll know it’s working if the fever breaks, the doctors say.

Your second dose comes on March 17, the same day the hospital stops allowing visits for anyone who isn’t dying or giving birth. Today is Dawn’s last visit. “We need you to keep fighting,” she says, squeezing your hand, fumbling words through emotion. “Your daughter starts school next year. You need to be here.”

Fight now, Ben the stubborn, and meet your fate this St. Patrick’s Day, as the world shuts down around you. Feel your sister’s embrace, her words like sunlight in your clouded mind. On this day, after seven days of intubation and hallucination and tears and shock, the fever breaks. On this day you wake up.

You can’t move. The ventilator hurts your teeth, sucks moisture out of your mouth, leaves you aching to drink. The vent tube clogs, and suddenly you are drowning, flailing in deep water. The hospital staff clears it; seconds that feel like hours.

On March 19, you start bleeding internally near your hip. A bleed means stopping blood thinners, and that means you, the first COVID-19 patient in the Western Hemisphere to survive going on ECMO, must now survive coming off ECMO.

But you have cause for optimism. After 10 days of lying nearly motionless in a hospital bed, the therapy team encourages you to stand. Three days ago, you couldn’t even hold yourself up on your side. Now, your hands brace, legs waking from stasis, hot blood rising in your face — and now you’re on your feet, the first known COVID-19 patient to stand up while on ECMO.

When the ECMO removal operation begins on Sunday, March 22, something compels Deanna at home to go to your treadmill. She remembers that time you visited her family in Canada, just four months into dating, back when you were a graduate student in chemistry at Notre Dame. Before you left, you placed your hand on her heart and said: “I’m not gone. You have my heart.”

Standing on the treadmill, she starts to run. Slowly, then faster, tears course down her cheeks. Her hand rises to her heart, just as yours did all those years ago. Through the tears, she repeats: “I will breathe for you, I will run for you.” A prayer, a spiritual conveyance, a thunderbolt, as you are freed from the ECMO machine. Heed her words, Ben the willing. Marshal your lungs to work again.

Survey your life in the quiet moments: If it had ended, would I have been proud of what I did? Would I have been happy with the life I was living, with the work I was doing?

On March 23, Dr. Eric Andersen, your physical therapy lead, helps you summon your legs. You clamber off your bed, steady yourself. Three footsteps forward, three back, because that’s as far as your tubes will allow. Each step is exhausting, euphoric.

Remember your Ironman mantra: Don’t stop, don’t quit, keep moving forward. A new journey is beginning, and this is how: with one step, then another, and another.

You start training for your next Ironman as a joke, or something like it.

By the time your ventilator comes out and you test negative twice, COVID-19 has torn you down to your foundations. You tell your daughter you’ve had “tiger germs” clawing and roaring inside you. You need an oxygen tank, you’re still in kidney failure, and you’ve lost 45 pounds. Brain fog, anxiety about breathing, persistent numbness in your left leg.

When they finally wheel you out to Dawn’s car, on April 6, the hospital staff line the hallways, cheering. You burst into tears, thanking them. They’re cheering for me when I should be cheering for them. Up your driveway, past the pine, and you are home, alive, springtime’s full heart bursting. Embrace your family: We get to have more of this life together.

But you are exhausted and emaciated. You kneel down to hug your daughter but need Deanna to pick you up. Ten minutes with the oxygen machine to catch your breath. You can’t even climb the front steps.

So on April 23, when Mike Reilly invites you on his podcast and graciously asks if you’ll ever get to an Ironman starting line again, you all but laugh it off: Sure, Mike. I’m still signed up for Ironman Arizona in November. Why don’t we see what happens?

You have no intention of doing it, of course. The oxygen machine is sitting on the floor next to you as you speak.

Then Reilly sends you his book about the competition, inscribed, “Dear Ben: You are an Ironman. Stay strong, keep pushing forward. See you in Arizona.” Now the challenge is in writing. After 28 days fighting for your life, you wonder: Have I lost some part of myself? Will COVID-19 define me forever?

You declare it to your family on May 3: You’re running Ironman Arizona in six months.

You start slow: a treadmill running program designed by ultraendurance athlete Tommy Rivs. Jason drives the hour to train with you: the brotherhood of suffering reunited, camaraderie strengthened by near-death, finding the blessings in hard things.

An ESPN producer, Scott Harves, gives you a call: He’d like to make a documentary about your experience. He and his crew are there for your first post-COVID-19 swim in Lake Ann, on May 19, and for your first 5K with Dawn and Deanna on June 14. You clock 35 ½ minutes, right on pace.

While you gain strength, the virus decimates more lives. Soon there are others like you with long-term symptoms, and you realize you’re not alone in this anymore, you can’t remain anonymous. Now you’re a survivor with a mission and a story to tell. Through Ironaid, an arm of the Ironman Foundation, you set a $10,000 fundraising goal to pay for COVID-19 patients’ hospital care.

You attempt the Grand Teton Picnic on August 1 alongside Jason and your other training partners: rhinos on the Serengeti reunited. You hang with the group on the ride and the swim, but you start to fade six miles up the mountain. Your hemoglobin levels still aren’t what they should be — Ironman lacking iron — and you’re breathing so hard you don’t notice the juvenile grizzly bear cross the trail 15 feet behind you. You can’t make the summit, not like this. You climb down the mountain, tearful, determined not to fail again.

Not all obstacles are physical. You and Deanna fear what COVID-19 might do to your daughter. You decide she’ll face less risk in New Brunswick, where Deanna’s family lives. She and Deanna move there on August 21; you aren’t a Canadian citizen, so you stay back.

Depression wells up. Days of solitude, family contact reduced to daily FaceTimes. A voice in your head sneers: What are you thinking? You shouldn’t be pushing yourself. Stay in bed. You start working with a counselor. You remind yourself: We’re separated to keep the family safe. You find peace on long runs, even in black fly season, even in snowstorms. Nine workouts a week, hours each day, miles to go before November. . . .

Ironman Arizona is canceled. In a fit of obstinacy, you don your wetsuit and stomp down to Lake Ann. The shivering ESPN team watches you swim 200 yards through icy water, crawl back onshore, and set your sights on Ironman Texas in April 2021.

That January you move to Canada. Reunited again. Now training is an act of sheer will: After all these days and miles apart, how can you say goodbye again for a five-hour bike ride?

Then Ironman Texas is canceled, too.

But when decision day comes for Ironman Tulsa in May, you get your chance. The race is on.

Rise now, Ben the remade, and seize your fate under the darkened Oklahoma sky. May 23, 2021, 14 months since you took your first steps in the hospital.

Your daughter has painted your toenails bright red. A memento. Here you stand, just before 5 a.m., wearing a tiger-print tracksuit over your wetsuit and green swim cap. Tiger germs: Deanna’s idea.

In your wetsuit you carry a laminated picture of them. They’re making faces, wearing their Ironman Support Crew T-shirts. Deanna has added plain text boxes: “We love you, we miss you, you can do this.”

They couldn’t make it, not with the travel restrictions. Jason, intent on being your sherpa, can’t be here either. Only Dawn and your nephew are here, seeing your journey through.

You lie down on a picnic table under some trees. A light drizzle falls on your face, and you cry. A wave of loneliness hits you even as the moment reverberates through your soul. After the hospital, the recovery, and two canceled races; after living apart, then reunion; after long COVID, numbness, brain fog — after all that: I can’t believe I’m here.

Just before the swim, you hug Dawn and your nephew near the start. Your nephew has Deanna and your daughter on FaceTime. You give them one last virtual embrace, and then you are in the water.

Swim, bike, run. No more thinking, just the euphoria of doing, of muscle and heart and lung in symphony once again. Hour after hour, mile after mile: Legs churning, mind at peace, animated by new purpose. Now you run with larger footsteps. Now you run for the long-haulers, and for all those who weren’t fortunate enough to have a Dawn by their bedside, to have your care team.

Now you run for Deanna, who ran for you, who breathed for you. Now you run for your 4-year-old daughter, to show her: Yes, Daddy almost died. But Daddy’s still here, trying to get better.

Night falls. You walk the last half of the marathon. Three blocks from the finish line, the lights and cheering rise around you, electric in the night. Hear, Ben, Mike Reilly’s voice telling your story, the story of someone who lives. Feel the emotion rise in your chest. Hear the words: Ben O’Donnell, you are an Ironman! Jason, watching the livestream, sheds a tear, checks his watch: 40 minutes faster than your first Ironman time. Here is Dawn with your medal, here is your nephew, here are your daughter and Deanna, a chorus of I love yous across 2,000 miles, and they are crying, and you are crying, because we did it, we did it, we did it.

Epilogue: After Ironman Tulsa, Ben O’Donnell ’06 M.S. became a full-time consultant and motivational speaker as president of Better Tomorrow Consulting. His hospital care team documented his physical-therapy regimen, a milestone in rehabilitative care for COVID-19 patients on ECMO, in an article published in the Journal of Acute Care Physical Therapy. O’Donnell testified about his COVID-19 experience before Congress on November 10, 2021. A day after his testimony, he presented his finisher’s medal to the care team at M Health Fairview, where it hangs outside his old ICU room.

Michael Rodio is a writer and former intern at this magazine. He lives in Brooklyn. Special thanks to Jimmy Franklin and Robert Rodio for audio recording assistance.