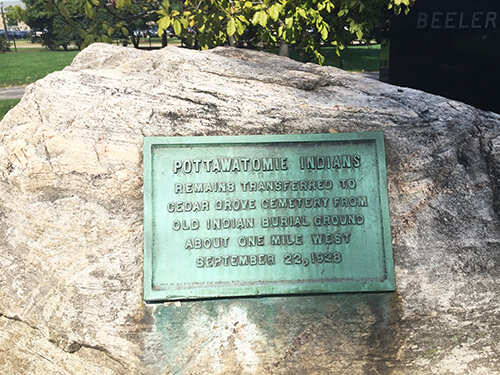

A valued but nearly forgotten history rests beneath the wet grass of Notre Dame’s Cedar Grove Cemetery, where several decorative rocks lie scattered among the headstones. One rock is adorned with a weathered green plaque marking the grave of “Pottawatomie Indians.”

Several bodies were moved to this site from a nearby Potawatomi burial ground in 1928. These days, few on campus pause to consider what and who was here before Father Edward Sorin’s famed arrival in 1842. Yet when we do we will find a story still alive today.

Notre Dame’s four-day Sustainable Wisdom Conference earlier this month aimed to highlight ways in which indigenous knowledge can work with modern thinking to inform a sustainable future. The conference opened with a physical exploration of the Potawatomi story. Brian Collier, a Notre Dame professor of American studies and poverty studies, guided a tour of its most noteworthy sites across campus.

Most among the tour group of students and alumni who share passions for sustainability were used to traversing Notre Dame’s quads, but this particular late-summer walk called to mind a colder day years ago when Father Sorin trekked through the snow with several Holy Cross brothers and saw the land around the lake for the first time.

As we approached the Log Chapel under blue skies on that Sunday afternoon the vision of Sorin pioneering melded into images of Sorin teaching, preaching and sleeping in the precursor to this rustic building. Inside, above the wooden chairs, hangs a mural depicting Native Americans who worshipped here by candlelight before Sorin came. The presence of this community of Potawatomi thriving by the small lake affirmed for Sorin that he’d found the right place to build his university.

Notre Dame records suggest that many of Sorin’s first students were French. Collier explained that while they had French names, some were likely members of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi.

As we left the Log Chapel, I noticed the lake’s sparkles with renewed interest. Many know that the yellow bricks of our oldest buildings came from these shores, but what do we know about the Native American students who helped dig the marl and build with it alongside the French priests and Irish brothers of the school’s early history?

Collier described the key role that the Potawatomi played in Notre Dame’s creation, but the land on which the University stands today remains a crucial component of Potawatomi culture. Dr. John Low, a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi and an assistant professor in comparative studies at The Ohio State University at Newark, asked to say a few words beside the chapel. He called our attention back to the cemetery, telling us that his Potawatomi grandmother, Sarah White, has the first grave immediately to the left of the entrance.

The Potawatomi connection to Notre Dame did not stop when Cedar Grove Cemetery became a private University cemetery in 1977 and their ancestors ceased being buried there. The tribal culture is inextricably linked to the land on which the Potawatomi have lived. Today, the Pokagon Band is centered in Dowagiac, Michigan, just 25 miles away. This region is their holy land. “We walk on the bones of our ancestors,” Low said. “That’s meant to be with pride.”

The final stop on Collier’s tour was the Main Building, where murals on the second floor depict controversial scenes from the life of Christopher Columbus. I was again hit with the realization that I walk by sites every day without acknowledging what they have to say to me.

Painted by the Italian artist Luigi Gregori and installed when the building was rebuilt in 1879, the murals depict the triumph of Columbus as a daring explorer and devout Catholic. They are meant to convey the importance of the Catholic faith and encourage us to accept Catholicism as an integral part of this nation’s history of conquest, settlement and expansion.

However, we might also ponder the flaws of the colonialist mindset that overpowered the Native Americans in the centuries since Columbus’ arrival. A story that compliments Catholicism through a different lens is the history of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi.

Nearly two hundred years before Sorin, the French explorer Robert de La Salle likely converted many of the Potawatomi to Catholicism, Collier said. Their faith persisted with the help of a succession of French missionaries. After the Treaty of Chicago in 1833, however, most Native Americans were removed from the American Midwest. Through the intercession of Father Stephen Badin, who had owned most of the eventual Notre Dame land before it passed into Sorin’s hands, the Pokagon Band received permission to stay because they were Catholic.

John Low emphasized that Catholicism was not a way for the Potawatomi to assimilate or protect themselves, but was authentically a matter of faith. “We can be Catholics and we can be Indians, too,” he said.

Low said he grew up with a Catholic faith shaped by the Book of Genesis and by his grandmother, Sarah White, who would take him to the Saint Joseph River near Mishawaka. There, she would explain, he was standing where “God, The Great Mystery, Creator, lowered woman to the earth.”

While their Catholicism allowed the Pokagon to remain on this holy land, their battle was far from over. In 1933 they lost their recognition as a sovereign tribe, which soon led to losses of autonomy and cultural knowledge. Potawatomi children increasingly attended boarding schools. The language diminished. Generations became disconnected.

But these developments would prove to be a pivotal moment of the Pokagons’ tale, not their tragic ending. Amidst the loss of culture, many in the band felt a drive to regain control of their lives and identity. After decades of effort, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi regained recognition as a sovereign tribe in 1994.

Their next chapter is still being written today. Like the cemetery and the Log Chapel, the icons of this modern story are all around us in the birch and black ash trees, the box turtle and the wild rice that speak of an ecological understanding that comes from living on the same land for centuries.

Through public events and outreach, the Pokagon strive to share their culture with the wider community, even as that culture faces new threats such as the emerald ash borer, an invasive species that destroys the trees that provide materials for the band’s basket weaving — a tradition rich in stories and symbolism.

The black ash crisis, along with the box turtle’s population decline and the degradation of endemic wild rice ecosystems, makes the this new battle one of common cause. The Sustainable Wisdom Conference was a step toward revitalizing the historic relationship between Notre Dame and the Potawatomi. At a time when we all face the consequences of resource degradation and environmental crisis, this seems to me an essential goal. Everyone stands to benefit from the renewal of a sustainable culture that may come through open discussion and the integration of today’s data driven research with ancient indigenous wisdom.

Natalie Ambrosio, an environmental science and journalism student from Sebastopol, California, is this magazine’s autumn intern.