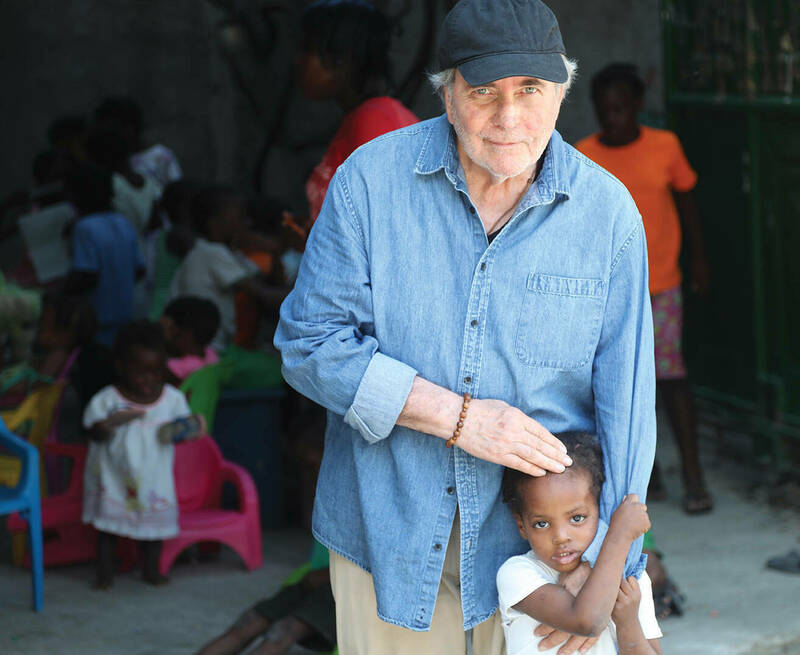

The Hollywood producer, itinerant seeker, author, filmmaker and follower of St. Francis found a home with the children of Cité Soleil. Photography ©2019 Santa Chiara Children’s Center

The Hollywood producer, itinerant seeker, author, filmmaker and follower of St. Francis found a home with the children of Cité Soleil. Photography ©2019 Santa Chiara Children’s Center

Moïse Straub, two weeks old, arrived at the front gate of Santa Chiara Children’s Center in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on the Ides of March, 2021. He was cradled in the arms of a woman who was not his mother. The real mother, after giving birth in the notorious slum of Cité Soleil, gave Moïse, Haitian Creole for Moses, to a stranger. Blood and fluid still covered the newborn. The distressed, teenage mother had begged the woman to tend the infant until she returned. She never did.

There was some reluctance among Santa Chiara’s staff to accept the child. Nevertheless, the founder, Gerard Thomas Straub, decided to keep the baby boy, even though Santa Chiara’s primary mission is caring for and educating girls. To turn Moïse away would send him to certain death in one of the world’s most impoverished, dangerous, filthy and degrading slums. Straub named the child, giving him his own surname and filing to adopt him. Moïse thus joined five other abandoned children also named Straub.

The odyssey of how Gerry Straub, 74, came to run a home for abandoned Haitian kids and become an adoptive father began many years ago under the bright, television-studio lights of New York City and Hollywood.

Straub grew up in a devout Catholic family in a middle-class neighborhood of Queens. His parents made daily Mass and the rosary hallmarks of family life. He attended Catholic grade school and served as an altar boy. A cousin was a Redemptorist missionary priest. Catholicism became an essential element within Straub’s young, sensitive mind.

At 13, he entered a Vincentian minor seminary in Princeton, New Jersey. He lasted two semesters. His dream of going to China as a missionary, he has said, “died at the hands of doubt.” The bigotry he had observed in his quiet Queens neighborhood as it progressed toward racial integration made him wonder why he should go to China to save souls when people on his own block seemed unchanged by Christian teaching.

After graduating from St. John’s Prep in 1964, the year the Beatles invaded America, Straub landed a four-week summer job at CBS in New York. His task was to answer mail-in ticket requests for the Beatles’ appearance on an upcoming episode of The Ed Sullivan Show. He completed the job in two weeks and spent the next two weeks “walking the corridors, poking my head into studios, marveling at the cameras, lights and sets,” he remembers. “It was a magical world that captivated my imagination.” Such tireless, teenage nosiness was readily noticed.

CBS offered Straub a clerical job and, to his parents’ horror, he took it, rather than going to college. Soon he was selected for an executive training program that placed him in a new job every three months. He accrued knowledge of the business so rapidly that at 21 he was made a full-time executive. Television became his life.

He worked at CBS until 1978. Several years later at ABC, he became an associate producer of the persistently popular, long-running soap opera, General Hospital. He worked with Elizabeth Taylor, Demi Moore, Tony Randall and others. At NBC he was the executive producer of another soap, The Doctors, that featured a young Alec Baldwin. One day, alone in his office watching his own show, he wondered, Who would watch this garbage? Straub was commercially successful, well paid, but deeply unfulfilled.

In 1987, approaching his 40th birthday, he produced his last soap. He wanted to channel his creativity into literary fiction, so he retreated to upstate New York, reading works of philosophy and theology. In spite of those influences, he wrote two books mildly in support of atheism, one of which was a dark novel about a man so exhausted in his search for God that he committed suicide. Straub describes the book as an angry scream at the Catholic Church. It did not sell.

The second novel was about a writer obsessed with the disparate lives of Vincent van Gogh and St. Francis of Assisi. After two more years of writing and feeling stuck, Straub decided to visit Arles in the south of France, where van Gogh had spent some of his most prolific years. He also decided to visit Assisi in Italy in hopes that the spirit of the two men, still alive in those distant towns, would inspire him to complete his book.

But within a month, something happened that Straub had not anticipated: 22 children were living and sleeping at the daycare. Their mothers had dropped them off but never returned to pick them up.

During his many years away from God and the Church, Straub had remained friends with a Franciscan friar who kindly tolerated his unbelief. He now asked him for help finding accommodations in Rome. That’s how, in March 1995, Straub arrived at the gate of the friary at Collegio Sant’Isidoro, a 400-year-old seminary run by Irish Franciscans. He was led to a small, austere room and told he was welcome to join the friars for dinner. The days were his to wander the busy, noisy, fascinating streets of Rome on his own.

After unpacking and heading out with an explorer’s enthusiasm, Straub passed an open door to Sant’Isidoro’s church. A beautiful statue caught his eye. He entered, but not to pray. He looked around, admired the architecture, then decided to sit and rest for a moment in the quiet, peaceful, darkened nave.

“This empty church and an empty man met in a moment of grace,” he recalls in The Sunrise of the Soul, a spiritual memoir. As he rested in the silence “something highly unexpected” happened: “God broke through the silence. And everything changed. In the womb of the dark church, I picked up a copy of the Liturgy of the Hours and opened it randomly to Psalm 63. In boldface above the psalm it said, ‘A soul thirsting for God.’ As I read the words of the psalm my soul leapt with joy: ‘God, you are my God, I am seeking you, my soul is thirsting for you, my flesh is longing for you. . . .’

“Without warning, I felt the overwhelming presence of God,” he continues. “I felt immersed in a sea of love. I knew . . . that God was real, that God loved me, that the hunger and thirst I had felt for so long could only be satisfied by God. In that moment of revelation, I was transformed from an atheist into a pilgrim.”

At Sant’Isidoro he attended morning and evening prayer and daily Mass. He hadn’t been part of the Church for over 15 years, nor had he received the Blessed Sacrament. One evening the guardian friar asked Straub if he’d like to talk for a while. That simple, gracious invitation commenced a three-hour conversation culminating in the sacrament of Reconciliation. Straub felt intensely liberated. The next day he received the Eucharist. From that moment, he adopted St. Francis as his spiritual guide. Over the years, Assisi would become his spiritual home.

Another friar introduced him to a Jesuit priest, head of the communications department at the Pontifical Gregorian University. Quite unexpectedly, he was asked to talk to a class and give students the chance to question a former Hollywood producer. That led to an invitation to teach a two-week course on creative writing for film and television in September 1995.

During his first fall of teaching, Straub met Father John Navone, a Jesuit professor of theology at the university and literary figure of some note. Straub told him about his van Gogh-St. Francis novel, and the priest offered to read it.

That December, Straub received a 10-page letter in which the priest, “cut my novel to pieces . . . bluntly telling me how the novel did not work on any level.”

But there was more. On the last page, Navone wrote, “The writing on St. Francis is the best I have ever read. Throw this book out and write a book about St. Francis.”

Straub took that advice and spent four years writing about the saint he loved, hoping to come to understand Francis’s love not only for the poor, but for poverty itself. Voluntary poverty was for St. Francis a way to be utterly dependent upon God for everything. A pragmatic man, Straub found that concept difficult to grasp, especially within the materialistic culture from which he came.

And yet for all Straub’s difficulties in trying to understand the saint, the Catholic Press Association in 2001 named his book, The Sun & Moon Over Assisi, the best spirituality hardcover book of the year.

Hoping to gain a deeper understanding of St. Francis’s love for poverty, Straub lived for a month with Franciscan friars who served the homeless at St. Francis Inn in Philadelphia. The experience was transformational. Every conception he had about homeless and addicted persons was wrong. He found instead they were real people, people he had callously and shamefully dismissed as worthless. The friars who dedicated their lives to serving the poor inspired him to make a film about St. Francis Inn. With the help of a friend from Good Morning America, he assembled a crew and shot the film in only four days. Incredibly, that humble effort, We Have a Table for Four Ready, was picked up by PBS and broadcast at Thanksgiving time for many years.

The friars of the inn have received thousands of dollars in donations from viewers of the film. They have a waiting list of volunteers. Donated funds expanded the kitchen and added a second-floor chapel. Every day about 60 people, many recovering from addiction, attend Mass at the inn.

The film’s impact revealed a new purpose for Straub’s life. He felt impelled to “put the power of film at the service of the poor.”

In Rome, the head of the Order of Friars Minor, who had read and liked The Sun & Moon Over Assisi, summoned Straub for a visit. Straub expressed how he was still struggling with the meaning of poverty in his life. He then asked permission to live somewhere, anywhere, with friars as they served the poor. Three weeks later he landed in Kolkata, India. With him he carried an idea and several cameras. Over the next 15 months he visited 39 cities in 11 nations. He filmed and photographed the most horrific slums in India, Kenya, Brazil, Jamaica, the Philippines and Mexico. The products of all that travel, hardship and work would be a photo book, a short film narrated by Martin Sheen, and the affliction of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Scenes of suffering in a slum would flash across Straub’s mind, causing him to weep. He had taken thousands of vivid, pain-filled photographs trying to understand the cruelty and senselessness of poverty that was killing millions around the world, including countless children who were dying from malnutrition and curable diseases. Filming people who were living and dying in filth and squalor filled him with an unshakeable sadness. He wrote about those “lost and forgotten, their desperate lives not important enough or worthy enough to save. They were disposable people.”

He spent hours studying and selecting photographs to include in his photo book, When Did I See You Hungry?, published in 2002. The task became a nonstop horror show running wildly in his mind. And yet, when it was completed and as the years went by, he continued filming and photographing in Uganda, Kenya, Brazil, Peru, Honduras, El Salvador and Haiti. Everywhere he went deepened in his mind, heart and soul the harsh reality of the unjust, unwarranted, unnecessary suffering caused by the affluent world’s unwillingness to unselfishly share and care for these least of our brothers and sisters, all beloved children of God. For Straub, not helping those in need became the greatest sin of a heartless humanity.

Today, in addition to having made two dozen documentary films on global poverty, Straub has published seven books and documented homelessness in Los Angeles, Detroit, Philadelphia and Budapest, Hungary. Since 2002, he has given over 250 presentations at churches, high schools and colleges across the United States, Canada, France, Italy and Hungary. His work has earned him honorary doctoral degrees from three Catholic universities. He has lectured and shown his films at many Catholic universities, including Notre Dame in 2002 and ’04.

Was it destiny that placed Straub in Port-au-Prince in December 2009? He had gone there to do what he had done in so many other cities. His first visit to Cité Soleil — City of the Sun — would prove haunting: a decrepit landscape of tin shacks, tarpaper roofs, rotting garbage and open sewers. He saw a little girl urinating on a heap of trash, a woman openly defecating, naked children with bloated bellies running barefoot through pig-infested mud. The putrid, nauseating stench was intensified by the unrelenting sun. It was almost too much for this sensitive man, so deeply afflicted by years of bearing witness to the world’s worst poverty. It left him feeling helpless and devastated. He retreated to his home in Burbank, California, for Christmas and New Year’s, but celebrated nothing.

Then on January 12, 2010, miles beneath the rough roads of Port-au-Prince and the nearby city of Léogâne, a contractional deformation along a fault line generated a large-scale earthquake. Poorly constructed concrete and masonry buildings collapsed, killing more than 200,000 people and leaving more than 1 million without shelter.

A week later, Straub was invited to accompany a medical team flying from Dallas to Port-au-Prince on a plane crammed with medicine and equipment. He was to film their relief efforts. With less than three hours’ notice, he joined the 22-member team to load the 737, filling the cargo hold and every unoccupied seat with supplies.

When the plane landed in the destroyed city, Straub felt he had entered an inferno of suffering and despair from which few would escape. The choking odor of dead bodies entombed in flattened buildings sickened him. Streets strewn with mangled or burned corpses horrified him. Seeing a young boy’s decaying foot stick out from the rubble of his ruined school and the skeletal remains of a person burned to death, charred his mind and memory. Amputations were performed without anesthesia. It was more than Straub could bear. He wept, not fully realizing that his life was being changed far more radically than when he had left the hollow glamour of Hollywood more than two decades before.

He again developed PTSD. He knew he had to stop filming the poor. It was not enough. In the spirit of St. Francis, he knew he needed somehow to serve the poor, walk with them, live with them, become poor with them.

The Haitian government banned all incoming visitors from the U.S. For a week, empty commercial planes landed in Port-au-Prince to fetch Americans home. Family and friends urged Straub to leave.

By 2015, Straub was living in a deeply impoverished section of Port-au-Prince. He heard gunfire almost every night. In the beginning, he simply intended to provide daycare for the children of poor women who earned very little selling homemade goods on streets too dangerous for kids. As in so many other cities of the world, children would be dropped off at the daycare in the early morning and picked up in the early evening. But Port-au-Prince is no ordinary city. Straub learned of one street-vending mother who sold homemade pasta. A man demanded a free bowl. She refused. He shot and killed her little boy who was seated on the ground beside her.

To help prevent such incomprehensible tragedies, Straub planned to shelter, feed and entertain such kids, keeping them safe and busy until their mothers returned to take them home, a home that was probably a mere shack with no running water or electricity. But within a month, something happened that Straub had not anticipated: 22 children were living and sleeping at the daycare. Their mothers had dropped them off but never returned to pick them up. He would learn this was not unusual. A hospital where he had taken kids for treatment asked him to take in children who had been abandoned there. Even Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity asked Straub to welcome unwanted kids left at their gate.

Within two years, 72 youngsters of varying ages were living with Straub and his growing staff. An infant was brought to him at two days old. His distraught mother had left him on a garbage dump to perish amid the filth and rats. Straub well understood that the daycare by necessity had evolved into a refuge and orphanage for homeless and parentless children, especially for girls, who are most vulnerable. He knew the daycare had to become a home. He made it one.

Straub named his center in honor of Santa Chiara, St. Clare of Assisi, who was St. Francis’s most faithful follower. By selecting that name, he wished to impart a Franciscan spirit to the home. Santa Chiara is unlike traditional orphanages. It’s more akin to a field hospital for kids, many of whom come to Straub seriously ill and often severely malnourished. Santa Chiara is essentially a sanctuary. Initially the motto was “A Place for Kids to Be Kids.” In time, as the daycare transitioned into an orphanage, it became “A Home of Hope and Healing for Kids.”

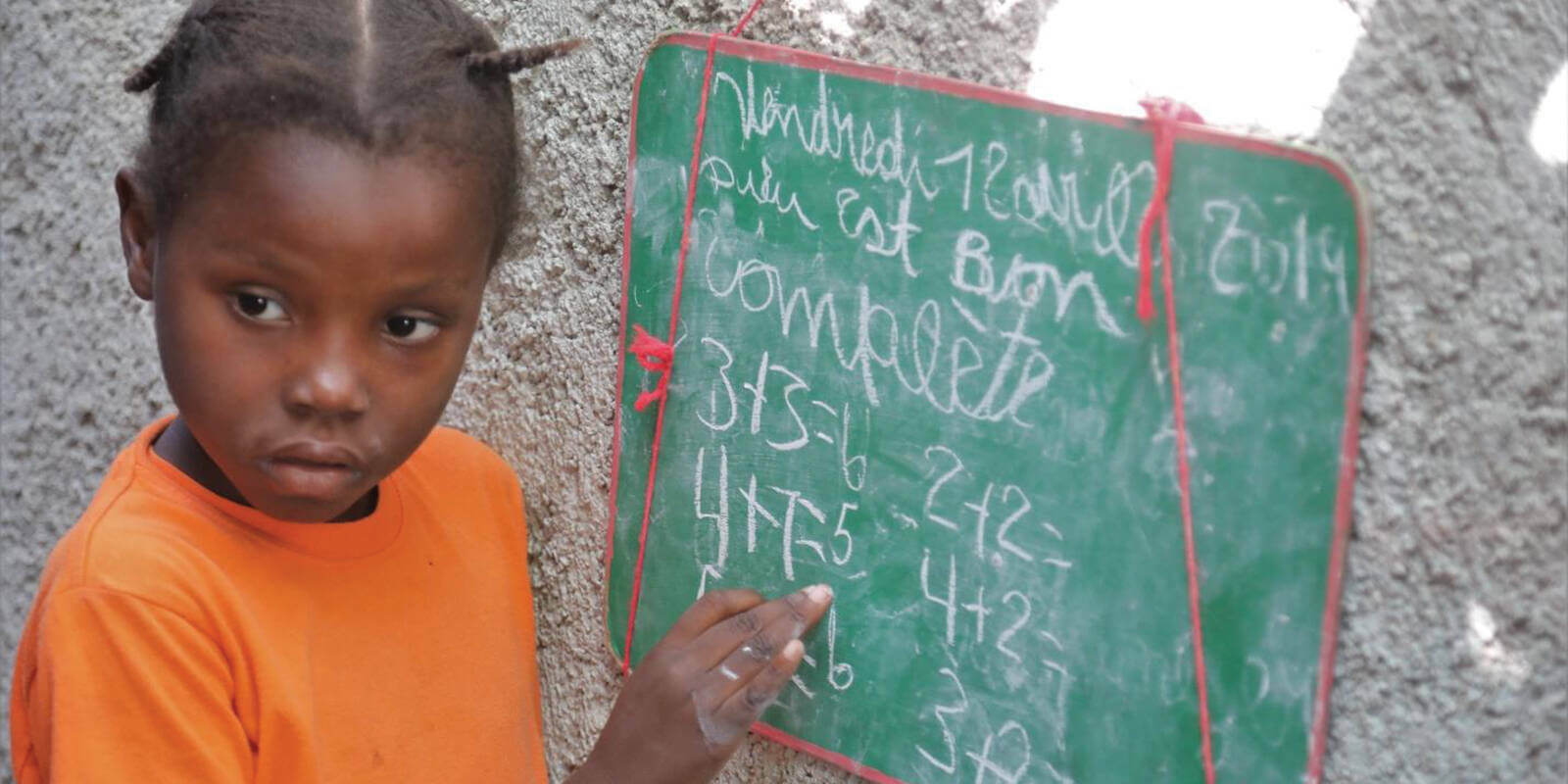

The unwanted, unwashed, homeless, abused and abandoned children of Cité Soleil are on a tortured exodus to nowhere. For them there is no promise, no hope and no future. They live within an abyss of despair. Yet among them Straub found his authentic life and learned the true meaning of sacrificial love. Santa Chiara is a place where some of the children of Cité Soleil get a chance to be safe, to grow and to learn.

Presently, Santa Chiara is housed in its third building, which provides comfort, cleanliness and physical safety. Many of the children have been there for six years, right from the start. They know nothing of the violence and mayhem that often occurs outside the walls of their home. The Missionaries of Charity often visit, as does a Passionist priest from Mexico and several of Straub’s priest-friends from the U.S. Everyone marvels that Santa Chiara, in the words of one visitor, is the “happiest orphanage” they have ever seen in Haiti. The sincere love among the staff and children reflects brightly in their eyes.

In the last several years, the number of children living at the center has gradually reduced. Some were moved to orphanages that could better meet their needs. Others returned to their families in cases where the parent or parents were again able to care for them. Family reunification, though rare, is always a priority.

Thirty-six Santa Chiara children attend an excellent private school. The center has a fine medical clinic staffed by two part-time nurses, one assistant nurse and two part-time doctors. One doctor is a highly regarded pediatrician at a nearby children’s hospital. The other lives in the neighborhood. In addition to her normal hours at Santa Chiara, she is called upon for emergencies — Straub himself once needed five stitches in his head after a nasty fall. With more than a dozen kids in diapers, the clinic has been an invaluable part of the center’s success. Tragically, in Haiti, many poor children never reach their 5th birthday.

In the last two years, many charitable organizations have fled Haiti. In March 2020, when the coronavirus became a pandemic, the Haitian government banned all incoming visitors from the U.S. For a week, empty commercial planes landed in Port-au-Prince to fetch Americans home. Family and friends urged Straub to leave. But he knew if he left, he would not be able to return to his kids for a long time. That was unacceptable, so he chose to stay.

Two months later, he was struck with COVID-19. The Missionaries of Charity obtained oxygen tanks that kept him alive for seven critical days. The superior was so sure Straub would die that she sought a priest to administer last rites. After he recovered, he developed a boil from a MRSA infection. It had to be lanced at a hospital that had no Novocain. Two attendants and a priest held Straub down. He screamed throughout the torturous procedure.

Because of Haiti’s deteriorating social, economic and political conditions, including the assassination of an unpopular president, the past few years have seen escalating civil unrest and gang violence. Initially, gangs disrupted traffic by setting up strategic roadblocks of burning tires, their black smoke fouling the already polluted Caribbean air. Then they began burning supermarkets and pharmacies. Straub’s life was threatened when he and an 8-year-old girl were driving home after attending Mass at the Missionaries of Charity chapel. They were surrounded by a gang holding gasoline cans above the car and threatening to set it ablaze. He pleaded with the gang leader to let the girl go, let her live. Mercifully, the man let both of them go.

By early 2021, people were killed or kidnapped on a daily basis. Straub had to travel with an armed guard. Then, in May and June, a lull in the kidnapping occurred, but word on the street was that it would soon start again. Seventeen members of the U.S.-based Christian Aid Ministries were kidnapped in October; by December all were released or had escaped. Father Tom Hagen, a friend of Straub’s who has ministered for 30 years in the slums of Cité Soleil, has said that “no one in the States can ever understand the reality of Haiti.”

Straub often wonders why, in his near-old age, he’s in Haiti running a “happy orphanage.” By his own admission, in a professional sense, he really doesn’t know how to run an orphanage. Drawn to the solitude of monasticism and the contemplative life, he lives in a crowded slum where screaming kids, crying babies and gunfire are the soundtrack of his daily life. Every day in Port-au-Prince the potential for deadly harm persists. Nevertheless, he remains in Haiti saving the lives of precious, innocent children dealt a very bad hand, kids who matter little to few outside the staff and supporters of Santa Chiara. He’s rooted in Haiti because he cannot and will not abandon them. His devotion defines the truest meaning of sacrificial love.

Straub writes, “The slums of Haiti exist because we as the human family have forgotten God and turned our backs on God’s children.” Difficult words to be sure. But Gerry Straub has the right to say them — to shout them — because he has turned with open arms and heart to the least of God’s unwanted, unloved little ones.

A graduate of the Program of Liberal Studies, Joseph Lewis Heil is the author of two novels: The War Less Civil and Judas in Jerusalem. He resides in suburban Milwaukee.