“Where is Victor?”

Like a sniper’s bullet, the unspoken question ricochets through the group, drawing blood when the implications hit. Victor Deupi, Notre Dame assistant professor of architecture, is the leader of this intrepid band; without him we haven’t a clue what to do. Once that initial zing has sunk in, a silent follow-up volley hits: What could be wrong? What are they doing with him? What’s going on? And now what?

For me, the anticipation of going through Cuban customs had been worse than the reality. Our group had a valid license from the U.S. government to travel to Cuba for educational purposes; all the proper U.S. and Cuban paperwork had been completed. When my turn came, the green-uniformed customs officer nonchalantly glanced at my passport, paper-clipped a visa to it and waved me through. “I hope you enjoy your stay in Cuba,” he said in flawless English. “Go through the doors.”

On the other side, in the baggage claim area, I discovered the ND group haphazardly split in two: those who were given a customs declaration form and those, like me, who were not. The “haves” were busy filling out the form while the “have-nots” were busy badgering the “haves”: “Where did you get that?” “Do I need one of those?” “Why didn’t I get one?”

The form presented a dilemma. We had been urged, as a humanitarian gesture, to pack extra toiletries and nonprescription drugs. Such items are in short supply and greatly appreciated by Cubans. Stashed in my bag, therefore, I had $50 worth of toothbrushes, toothpaste, aspirin, antibiotic ointment and Band-Aids. The monkey wrench was this: My “aid packet” was addressed to no one in particular.

On the flight to Havana I had read in a 15-year-old guidebook that the Cuban government allowed such humanitarian parcels only if they were labeled for a specific individual. But was the information outdated? Should I declare the items? Or do the officials look the other way? I had meant to ask Victor, but no matter. Before I could resolve the issue, we were herded toward a uniformed lady talking to him. She unfastened a velvet rope at a stanchion and waved us through and out the door. We were in Communist Cuba . . . but Victor was not.

So now here we stand, the 10 of us — nine senior architecture students and one slightly bewildered associate editor along for the ride — milling around the curb outside Havana’s Jose Marti International Airport. Our reason for being here is three-fold. We have come to study the architecture and urban plan of Havana and the colonial town of Trinidad; to establish ties with Cuba’s leading academic architects; and to reconnect with the Notre Dame School of Architecture’s Cuban heritage. But, at the moment, all that seems in doubt.

A small tour bus pulls up, and someone official directs us inside where we wait five, 10, 15, 20 minutes. Finally, looking slightly stressed, Victor emerges from the terminal and gets on the bus. The bump in the road, whatever it was, has been smoothed. The bus pulls away and we head to central Havana. Our documents say we are staying at Hotel Cocina, but Yaritza, our official guide from Havanatur, says there’s been a change. Instead we will be staying at Hotel Flamingo. After a 30-minute ride, the bus pulls up to a five- or six-story ’50s vintage building whose sign says “Hotel Horizontes Vedado.” A mistake? “No, no. Same thing,” Yaritza says without explanation.

And what’s in a name after all? You say Flamingo; I say Vedado. For the next five days, for our purposes, it will be Notre Dame-Havana. We drag ourselves and our luggage into a small lobby remarkable only for its Pepto Bismol pink walls, which, like many of those in this city, are peeling in patches. The clerk checks us in and one-by-one we wander off in search of our rooms.

On the second floor I find mine clean, modest and slightly worn but with a small touch of elegance: Somehow the maid has twisted the bath towels into an amazing sculpture of swans nesting in the center of my bed. Each day, I will discover, the sculpture changes, sometimes birds, sometimes hearts, always intricate. I feel slightly guilty destroying the artwork but after a very long day on the road and in the air, my need for a shower wins out.

This marathon day began 18 hours ago behind Bond Hall. We assembled there at midnight and then set out for the Indianapolis airport in a three-car caravan. A 5 a.m. flight took us to Charlotte, North Carolina, which led to a flight to Nassau in the Bahamas, where the ever-resourceful students used our six-hour layover for serious tanning time at one of the island’s fabled sugar-white sand beaches.

Finally, at 4 p.m., we boarded the Cubana Airline flight to Havana, a Soviet YAK 42 equivalent to a Boeing 727 but with some noticeable peculiarities. The doorway to the YAK is about 5½ feet high, so even I at 5 feet 10 inches felt like an NBA superstar ducking my head to enter. Just before takeoff, wisps of white vapor billowed from beneath the plane’s seats. The flight attendant assured us, “No worry. It’s just ‘normal’ air-conditioning.”

A few minutes later the steward passed a tray of hard candies (to take our minds off the white vapor?) and then we were airborne. Within an hour, or just enough time to serve refreshments and sell duty-free rum and cigars, we touched down smoothly on Cuban soil. The plane rolled to a stop and we clambered down the stairs, making our way across the tarmac to the international terminal where Victor’s Adventure in Customs began.

Behind us a woman softly sings in Spanish:

Clear the path of dry cane leaves

I want to sit down

I want to sit down on that trunk over there

Or I won’t make it at all

Her voice, like the evening sea breeze that cools us, undulates through the Cuban song, seamlessly blending with conga drum and guitar. The melody is a soothing backdrop to our deliberations. It is later in the evening and we are on the veranda of the Hotel Nacional sitting in white wicker chairs sipping mojitos, the Cuban drink made with white rum, seltzer, lime juice, sugar and a sprig of fresh mint.

Victor has summoned us to this place a few blocks up the hill from the “Flamingo/Horizontes Vedado” to “debrief and decompress.” It is ideal for the task. Set back from the street by a broad front lawn with a long drive lined with stately palm trees, the Nacional inspires two words: imposing and elegant. Unlike most of the buildings in this crumbling city, the Hotel Nacional is impeccably maintained. For the better part of a century, the Havana landmark has been host to the rich and powerful, famous and infamous. Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky once convened a summit meeting of the Mafia here, reserving the top four floors for mob “delegates.” Today, the Nacional’s guests include business people, dignitaries and wealthy tourists, but the ghosts, both notorious and respectable, of Havana’s freewheeling past still seem to lurk in its shadows.

As the woman on the veranda sways through another song, Victor fills in the details of his solo exploit at the Havana airport. The problem, he surmises, was provoked by his full name: Victor Luis Deupi y Santaballa. A Spanish-style double surname apparently triggers a closer look from customs agents than a name like Monczunski, for instance, which is less likely to belong to a disgruntled Cuban American intent on deposing the current regime in Havana.

“They were polite, but very thorough,” he says. “They looked through everything and were especially obsessive about documents. They wanted to know about anything in writing.” The customs agent went through his address book page by page, he says, but didn’t question the suspiciously large quantity of clothing he had packed. Finally satisfied that Deupi didn’t represent a threat to the state or carry dangerous contraband, the customs agent allowed him to join the Notre Dame bus idling at the airport curb.

We chat more on the veranda. Victor outlines the week’s agenda, then we walk to a paladar, a small, privately owned restaurant around the corner from the Nacional. Certain small private businesses are now legal in the country. Cubans, for instance, may operate restaurants limited to 12 tables or they may rent out tourist rooms in their home.

Dinner features entrees of pork or chicken accompanied with several dishes, including black beans and rice and fried plantains. It is topped off with wine, dessert, an after-dinner aperitif and cigars for the men and flowers for the women — all for $15 per person, including tip. Payment is in U.S. currency. The official currency of Cuba is the peso, but the dollar was legalized in 1997 and has become the standard of exchange for foreigners in the country. It is welcomed by the natives for its increased buying power.

We make our way back through the lush Havana night to the Flamingo and bed. We are exhausted — but full.

Orestes del Castillo is a friend and classmate of Victor’s father. The kindly looking white-haired man also is one of the leading architects responsible for the reconstruction of Old Havana. UNESCO has designated the old city, which was founded in 1519, as a “world heritage,” and those magic words have opened the door to international funding for restoration of the city’s colonial architectural treasures. The task is monumental — in every sense of the word. The old city contains some 4,000 buildings in Spanish baroque, neoclassical and art nouveau styles, most of which are crumbling. The price tag to erase all the decay in Old Havana has been estimated at $30 billion.

We walk through the narrow streets to del Castillo’s office, which is around the corner from the brown stucco Hotel Ambros Mundos. In a room there it is said Ernest Hemingway wrote the first three chapters of For Whom the Bell Tolls. Cuba, and Havana in particular, is Hemingway Country. Sometimes it seems there’s a place around every corner where Hemingway either slept or drank. A few blocks away are two of Hemingway’s favorite watering holes, the Floridita, which is the birthplace of the daiquiri cocktail, and La Bodegita del Medio (“The Little Store in the Middle of the Block”), a bohemian favorite known for its walls encrusted with graffiti. In a small town near Havana the Cuban government maintains Papa’s old villa as a museum.

After viewing an amazingly detailed model of Old Havana — but not the most amazing model we will see today — del Castillo takes us on a walking tour of Old Havana’s three main plazas: the Plaza de Armas, Havana’s first civic square and military parade ground; the Cathedral Plaza, dominated by its Spanish baroque church; and Plaza Vieja, the market square bordered by Creole palaces currently being restored. At each stop the arkie students haul out sketchbooks and swiftly render architectural details that catch their fancy. It is a ritual that will be repeated again and again this week.

On our way to the Cathedral Plaza, a street artist with pen and pad in hand hovers along the edge of our group. Stride-for-stroke the young man sketches as he walks. With quick, felt-tipped lines he draws a caricature of his unsuspecting subject — me. Within 30 seconds, he dates and signs the piece, rips it from the pad, offers it up and says in English, “Whatever you care to give.” There is a semblance of resemblance, so I pull $2 from my pocket, not a lot, but a fair price, and more than I think in a country where the average wage is $12 per month. The artist accepts the offering and nods in gratitude.

Walking back to his office, del Castillo gestures to a final point of interest: a garden nestled between some buildings. “This garden is in honor of Princess Di,” he says, adding that elsewhere in the city there is a memorial garden honoring Mother Teresa, who died within a week of Princess Di. In another part of the city, a square honors the memory of John Lennon. A princess, a saint and a singer make a curious trinity to be celebrated in a Marxist-Leninist state. But then, this is Cuba.

In the afternoon, another friend and classmate of Victor’s father gives us a guided tour of his pride and joy, a 1:1,000 scale model of the city of Havana. Depicting every building in every neighborhood, the entire city of Havana has been reduced to the size of a basketball court. Mario Coyula, in charge of city planning for Havana, walks the periphery using the red dot of his laser pointer to draw attention to details of interest as he traces the development of the city from its founding in 1519 as La Villa de San Cristobal de la Habana.

Like New Orleans, the Cuban capital was modeled after the Spanish city of Cadiz, he says. “Historically, Havana grew to the west from five main streets, from squares opening wider and wider.” When the walls of the old fortified city could no longer hold its growth they were torn down.

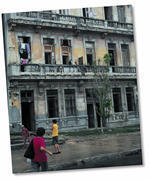

The further west one goes, the Cuban official says, historically the wealthier and less dense the neighborhoods became. Coyula acknowledges the obvious, “Many buildings in the city have decayed by lack of maintenance, by age, by many problems,” he says. And it is true there are tottering structures nearly everywhere. Inevitably, the stray well-maintained home either belongs to a foreign embassy or is a Cuban governmental office.

The apartment buildings along the Malecon, Havana’s famous seaside boulevard with its renowned promenade, are of special concern. “Over the years these have decayed to the action of the wind and sea,” Coyula says. "Restoring these buildings is a high priority.

“We are developing a general plan for the city to enhance development in an intelligent way,” he asserts. “The government has established a company that operates tourist hotels, restaurants and shops, and the profits from that help to underwrite the restoration of the old city.” He adds, with a note of approval, “The main money from the company, however, goes to social welfare.”

Although the city planner doesn’t lecture on the superiority of socialism, his political loyalties peek through in random asides. “A very important fact about our system,” he says while discussing development, “is the attention to children and family.” Another time he notes that a certain building was constructed “after the triumph of the revolution 1959,” a stock phrase used to date things in Cuba. Coyula’s presentation is the most political we have encountered, more so even than those of Yaritza, the official tour guide assigned to us for our stay. Even at that the rhetoric has been mild and understated.

A driving gray rain pelts our tour bus as we cruise east along the six-lane Malecon. The Atlantic is on our left, on the right the ochre, turquoise, cream and coral colored apartment buildings that Mario Coyula said were disintegrating from wind and wave — and one look confirms indeed they are. Bravo, our driver, has the radio on. It is 8 a.m., the height of the morning rush hour in any U.S. city, but here it is mostly smooth sailing. What traffic there is, however, is vintage: ’57 Chevys and Plymouths, ’54 Fords; any and every U.S. car from the ’40s and ’50s is represented. There must be more fins on the road than in Havana Bay. At least 30 percent of the cars are museum pieces, living fossils.

Students scrunch in their seats in a vain attempt at comfort and shut-eye as the bus radio sings in English with a bubbly Afro-Cuban beat “We got so much stuff,” a curious lyric in a country where people clearly do not. We are en route to Trinidad, not the island but the colonial town on Cuba’s Caribbean (south) coast. It is a five-hour drive along sometimes narrow and winding roads.

A corkscrew drive takes us into the tunnel that burrows under Havana Bay, linking Havana’s east and west sides. As we emerge from the tube the white stone walls of El Moro, the Spanish fortification guarding the harbor’s entrance, looms above us. Tomorrow we will tour the fortress as well as its neighbor, La Cabana, but now we pass them by. Within a few minutes Bravo has us cruising east along a four-lane divided highway, the main road running the entire 1,000-mile length of the island.

Two-and-a-half hours down the road we turn onto a two-lane highway that wends its way south to Trinidad. Gradually the terrain changes from tabletop flat farmland to rolling hills. We round a bend and finally there it is. The deep forest green Escambray Mountains and the cobalt blue Caribbean frame the town of about 60,000, which was founded in 1514, five years before Havana.

The rain has stopped and the blue sky is filled with puffy white clouds as we rumble into Trinidad at noon along its cobblestone streets, paved with ballast stones from Yankee Trader ships. Trinidad is something like Williamsburg, Virginia, only the docents actually live here.

After lunch we tour several modest private historic homes that have been opened to the public by their owners. Around one corner a few sidewalk stands ply their wares to passing tourists. Trinidad is renowned for the quality of its lace, and I purchase some place mats. By means of gestures, the elderly man and woman who operate the stall “talk” me into also purchasing a guyabera, the formal shirt/jacket with four pockets, two at chest level, two at hip level, popular in Central American and Caribbean countries. Purchase price for four lace place mats and the embroidered cream-colored guyabera — $15.

A horsecart carrying a schoolboy in his uniform (white shirt, gold pants) clops down the street. Around another corner some local children play the Cuban national sport, beisbol. At bat, however, is Notre Dame’s very own Eric “Kiki” Saul (Victor has given everyone a Cuban nickname), a student from Los Angeles who manages to get in every game we encounter.

In the Plaza Mayor, the center of town, a 7- or 8-year-old girl shadows Ariane Risto, a Notre Dame student from St. Joseph, Michigan. The little girl asks Ariane if she is French. Then, in French, she asks her for money for shoes. Ariane gives her 75 cents. The little girl spies Ariane’s pen and sketchbook and says, “You have two pens. Can I have one? You have two.” The girl walks away 75 cents and one pen richer.

Panhandlers and street hustlers in Cuba, whether large or small, generally are polite and, unlike those in some U.S. cities, nonthreatening. Some even are ingeniously enterprising. One man hovered around our Havana hotel, which specialized in university tours, hawking used hardcover books. “My frien’. Mi amigo. La cultura?” he would inquire, holding up the books.

From Trinidad’s main square we make our way to the Convent of San Francisco de Asis, now the Museum of the Struggle Against the Bandit Bands. Where nuns once prayed, displays of military artifacts now commemorate the government’s defeat of a band of counterrevolutionary guerrillas some time after the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Around 5 p.m. Bravo puts the pedal to the metal and we head back to La Habana. By sunset he hopes to be nowhere near these winding country roads. We sidetrack for a brief stop at the coastal town of Cienfuegos, the birthplace of Cuban jazz legend Benny More and the cleanest and best-kept town we have seen. Yaritza says it has always had this reputation, even before the triumph of the Revolution.

As promised, Bravo has us at the Flamingo doorstep by 10 p.m.

For Victor, Thursday morning is the emotional peak of the week. He and I take a cab to the Hotel Riviera parking lot along the Malecon. Dotting the ocean 100 to 200 yards beyond the Riviera are several “neumaticos,” fisherman bobbing in their inner tubes, the ingeniously inexpensive Cuban alternative to a fishing boat. For Victor, this is a pilgrimage in search of the holy places of family legend, a homecoming even though he has never before set foot in Cuba.

Victor’s parents, themselves both architects, fled Cuba in 1960. He was born four years later in the United States and raised in the Washington, D.C., area. His identity, however, is as Cuban as Desi, El Duque or Elian. Like many first-generation exiles, he feels a strong need to connect with “the old country.” To keep their heritage alive, his parents banded together with 11 other Cuban-American families in an informal group calling themselves the “Dirty Dozen.”

“We would get together on American holidays, celebrating them with Cuban food and music,” Victor recalls. When he was a child, his parents regaled him in Spanish with family stories of Havana, where one grandfather worked in the main office of the Bacardi rum company while the other grandfather supported his family as a professional gambler working the jai lai games. Now, finally, the places that have been only photos become real.

Armed with a map drawn by his father in the precise hand of an architect, we walk the streets of the once middle-class suburb of Vedado looking for the homes of Victor’s parents and other relatives. Suddenly Victor pulls up short. “There it is,” he says, pointing to a tall apartment building across the street. “That’s where my father grew up.” He pulls out his camera and starts snapping. Two older women emerge from a neighboring building, and Victor explains his relationship to the neighborhood and asks if they may have known the Deupi family. They are new to the area, however, and the name is unfamiliar. A few blocks away we find the apartment building of Victor’s mother, repeating the identical ritual with the same result.

On a tree-shaded street Victor stops before a three-story building across from the Bulgarian embassy. “My father went to high school here in the ’50s,” he says. “Then it was DeLaSalle Institute, run by the Christian Brothers.” Like so many buildings in this city it is punctuated with broken windows, peeling paint and crumbling masonry. The teens in and around it, however, suggest the building still functions as a school. A woman monitoring the entrance allows us in to photograph the school’s courtyard. The building, she says, is now a “school of transportation.”

Instead of hailing a cab, we walk back to the Flamingo. The walk is a pleasant one down a broad commercial avenue and takes about half an hour. As we trudge along, the impact of the morning sinks in. Victor shakes his head and says, “I keep thinking about my Dad walking up the street from home to school each morning. Thinking what it was like.”

Thursday afternoon offers the group a firsthand look at Notre Dame’s impact on Havana’s architecture. It comes in nothing less than the former capitol. Euginio Rayneri, who in 1904 became the first graduate of Notre Dame’s program in architecture, returned to his native country and was a leading member of the design team for the Capitolio, the seat of Cuba’s legislature until Fidel Castro’s regime assumed power in 1959. Rayneri served as technical and artistic director for the project, which was completed in 1929. The neoclassical building, which now houses the National Academy of Science, was modeled after the U.S. Capitol Building.

In 1910 Rayneri won first prize in an international competition for his design of the Cuban Presidential Palace. He was the founder and first president of the Colegio de Arquitectos, the Cuban Society of Architects. We roam the halls of Rayneri’s capitol building, taking a short break in the chamber of what once was the national assembly’s upper house.

Within the shadow of the Capitolio, appropriately enough since the product has so much to do with Cuba’s identity, stand the country’s two most renowned cigar factories: Partagas and Jose Marti (formerly H. Upmann). Like the Pied Piper, Yaritza leads us first to one, then the other. In what could be a scene from a “B” movie, a young man emerges from a darkened alley along the way. “Cigars?” he asks hopefully. “I have cheap.”

Cigar hustlers are a common sight, trolling Old Havana for tourists. Actually “common sight” may be an overstatement. Like anyone involved in illegal activity, they prefer to be invisible to everyone except their potential customers. The government frowns on the entrepreneurs because the cigars, of course, are stolen from its factories.

Rolled Cuban tobacco leaves are indeed gold. A six-pack of Cohiba Siglo IV cigars sells legally for $48 in Cuba. In the United States, the six cigars would fetch $150. Yaritza claims the secret to Cuban cigars is that they are a blend of five types of native tobacco. The tighter the leaves are rolled together, the better the cigar. American citizens traveling to Cuba with U.S. government approval are allowed to return with $100 worth of cigars or rum. Several of us easily reach that limit.

“This is the last day. I’m sad,” Victor says.

If Thursday was the emotional peak, Friday promises to be the academic peak. It is the day Professor Deupi and his class will meet Reuben Bancroft, dean of the school of architecture at Ciudad Universitaria Jose Antonio Echeverria (CUJAE), and present the past semester’s work, their drawings and “transect analyses” of Havana and Trinidad.

But first, there is an action-packed day of preliminaries: a tour of the Plaza de la Revolucion, including a trip to the top of the Jose Marti Monument, followed by an excursion to Cubanacan, the once-exclusive neighborhood sometimes called Country Club, and then free roaming/sketching time back in Old Havana.

It takes only a few minutes by bus to get from our hotel to the vast expanse known as the Plaza de la Revolucion. This is where El Comandante, the Maximum Leader, holds court over his subjects. Yaritza invites Victor to stand at the stone platform where Fidel Castro delivers his legendary marathon speeches to hundreds of thousands of Habaneros massed in the square. With the 450-foot-high spike of the Marti Memorial in the background I snap a picture of Victor for posterity. The stone tower is reminiscent of the Washington Monument. Indeed, Jose Marti, who led the 19th century revolt against Spain, is the Cuban George Washington.

Across the broad plaza are several government office buildings, including the Ministry of Interior, easily recognizable with its 10-story black metal outline image of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, Fidel Castro’s trusted lieutenant who was killed in 1967 leading an insurrection in Bolivia. The image on the building facade is derived from the famous portrait of Che, wearing a beret emblazoned with a Communist star.

The photo has been called the “most famous revolutionary image in the world” and during the 1960s in poster form graced the walls of student rooms worldwide. I have seen the image countless times this week. If this were the United States, I idly think, the photographer would be a wealthy man living off the royalties, and I wonder who the photographer might be. Ironically, on the flight home I get my answer in USA Today where the obituary of Alberto Korda catches my eye. The 73-year-old Cuban photographer who died in Paris on May 25 never attempted to copyright the 1960 image until last year when he sued an advertising agency which used the revolutionary icon in an ad for Smirnoff vodka.

Korda’s image of Che is everywhere in Cuba, but I have yet to see any of Fidel. In the theology of the Cuban revolution, the writer Andrei Codrescu argues, Fidel is God the Father and Che is the martyred Son. Perhaps that explains it. In Christianity, the Son is in every church, but, the Father, save for the occasional Sistine Chapel ceiling, is rarely seen.

From the bastion of the revolution we move on to the former bastion of the bourgeoisie. Country Club, once the poshest neighborhood of Havana, is home to the National School of the Arts. The five-school complex (modern dance, plastic arts, drama, music, ballet) is an “organic modernist” composition of red-brick domed buildings linked by red-brick vaulted walkways. The earth-toned, rounded buildings seem to grow from the landscape.

We hope to tour the complex, which rests on an old golf course, but there is a glitch. Since we have not made an advance reservation, the administrator on duty insists it is impossible. “But we are a delegation of American architecture students only interested in seeing the buildings,” Victor explains. “Perhaps we could merely walk through on our own?”

She is unimpressed and unyielding. Bravo, however, comes up with a solution. He drives a road along the periphery that affords a view of several buildings. It is enough, and we head back to Old Havana.

On the way we pass the gray tower that is the Russian embassy. “The vodka bottle,” Yaritza snorts. Today, the Cuban government has as little affection for the Russians as for Americans. Along the Malecon we pass another architecturally ugly diplomatic building, the eight-story gray Modernist block that houses the United States Office of Interests. Since the United States and Cuba have no formal diplomatic ties, the office technically is part of the Swiss embassy. In Washington, D.C., there is a comparable Cuban office also attached to the Swiss embassy.

At 5 p.m. Bravo picks us up at the Plaza de Armas in Old Havana and we make our way to CUJAE on the south end of town. He eases the bus through light rush hour traffic passing a pink “camel.” The color-coded express buses that serve outlying communities are peculiar to Havana. Their name comes from their distinctive passenger compartment, an extended trailer lower in the center than the ends, suggesting the two humps of a Bactrian. The passenger trailer is pulled by a large truck. “Like a camel in the desert, it goes long ways without stopping,” Yaritza says.

Victor has a personal connection with CUJAE. His father was a draftsman on the design team for the school, which began construction in 1961. The design is widely regarded as one of the most successful uses of precast concrete modules in school design.

Dean Bancroft welcomes us to CUJAE and ushers us to a classroom where the ND student work is presented. He clearly is impressed by the transect analyses rendered as water color drawings that depict set urban regions and their typical building configurations. The work, in fact, is stunning, suitable for framing. Bancroft is so impressed he suggests the possibility of a joint project involving CUJAE and Notre Dame. There are political realities to contend with, however, and he is aware the wish may not come true. “The time right now is not as good as it should be,” he says with a sigh. “But . . .” The final word hangs in the air hopefully.

As it must, the spell that has been this week finally breaks Saturday morning. Bravo and Yaritza drive us out to the Jose Marti international terminal and point us in the direction of home. Yaritza pecks Victor goodbye on the cheek then stumbles, smacking a red lipstick stain on his cream-colored jacket. The jacket may be ruined, but if his wife demands an explanation at least he has 10 solid witnesses to corroborate what otherwise might be a shaky story.

On the return trip everything is ho-hum familiar. The hard candy at takeoff, white vapor in the cabin. No surprises. The return, in fact, is a mirror image of the journey to Cuba, even to the point of difficulty with Cuban customs. This time a student, Aaron Cook, has been singled out. When we arrive in Nassau, Aaron discovers his luggage is still resting in Cuba. Bahamian officials explain that Cuban customs randomly spot check for illegal cigars. If they find cigars without a valid sales receipt, they confiscate the tobacco. The unlucky traveler has a 50/50 chance of being reunited with his luggage. Aaron is not happy.

From Nassau it’s a quick hop back to Charlotte. As we wait there for the flights that will scatter homeward-bound students in all directions, we already begin to reminisce about Cuba. The place has left its mark. The memory is intoxicating and will be for a long time.

John Monczunski is an associate editor of this magazine.