As public awareness of coronavirus took hold a month ago, I did what every New Englander, schooled by blizzard seasons, does instinctively: I went to the grocery store. Already, it was a transformed space. Although masks had not yet become part of Massachusetts’ recommendations, people were already improvising.

A leather-clad man in the produce section was wearing a red motorcycle helmet — with the visor pulled all the way down — while he browsed the avocados. An older petite woman beside the spinach wore two masks, one layered atop the other, a thick pair of lab goggles and a long angora scarf, wrapped in a fuzzy layered orb around her head.

It looked like a scene from Star Wars.

Already, we had become strangers to each other and perhaps a bit strange to ourselves, a process that has intensified as contagion has reshaped — in both subtle and radical ways — how we conduct our public selves and private lives.

That day in the grocery store, everyone kept a studious distance from each other, filling carts to the brim as if it were normal to be buying a month of groceries all at once. When I drove to my parents’ house to drop off eggs and cheese, pasta and milk, I left the bags on the porch, rang the bell and ran across the street like some teenage prankster.

My parents came to the door, fully dressed but bed-headed. Stepping onto the porch to wave, they looked frail and sleepy in the early morning light. In their late 60s, they have committed to staying indoors and to walking laps around their suburban yard for exercise. They have told me that their last will and testament is on the dining room table. Medical histories are in labeled envelopes on the refrigerator.

All documents, my mother assures me, are in order. And it’s as if she is saying, implicitly: All has been levied against death’s disorder. But should that come to pass, here are the instructions.

Indeed, our phone conversations shuttle disarmingly between the weather, the spiritual impoverishment of having no NBA playoffs or baseball season, good escapist novels, variations on the baked potato and their wishes, should they become ill. The cherry tree — and the virus — are in full bloom. It is, as my mother says, a most sobering time.

But it is also a time of stoic hope. We have survived plague before.

As soon as I got home from my first “corona” grocery trip, I showered and changed my clothes, rooting in the closet for an old comfort: a hand-loomed white Banff sweater worn by my grandmother. It is 80 years old, but still warm. Its warp and weft look delicate, yet it has proven to be sturdy and even stylish, over time.

That day, as I slipped it over my head, I did the math: my grandmother, Mary McCarthy, was born almost exactly nine months after the first wave of Spanish flu peaked in Boston in September 1918, ravaging a population already weakened by the stress of war. In Massachusetts, the flu catalyzed the closures of schools and the shuttering of public life, the saturation of hospitals and morgues, the deaths of overworked doctors, nurses, and orderlies. In some localities, the sense of social crisis was so intense it spurred suicides.

But my grandmother was conceived then, as if in defiance of death, and born to her parents in the seaside town of Winthrop, where she might have worn this sweater while sailing on a blustery day or later, going to a parish dance with her younger sisters. In a world in which touch and breath have become imperiling, this family hand-me-down is a reassurance. A message in a bottle.

“It’s awfully hard not being able to hug you,” my mother says on the phone after I drop off a second round of groceries, two weeks into the stay-at-home advisory. So I tell her that I have been wearing her mother’s sweater, which she also wore, for a spell, in college.

“It’s a well-knit hug from both of you,” I suggest, noting how my shoulders don’t quite fill the sweater the way my basketball player mother’s shoulders once did. Thinking of my mother’s healthy height — she is 5-foot-9 — makes me realize another coincidence, a second wrinkle in time.

This Easter Sunday and Monday, Massachusetts had its two hitherto highest daily death totals. We have not suffered the scale of loss witnessed in New York or New Jersey, and yet experts caution that our peak is still ahead. But Easter Sunday this year also marked an important date, one worth recalling: the 65th anniversary of a successful polio vaccine.

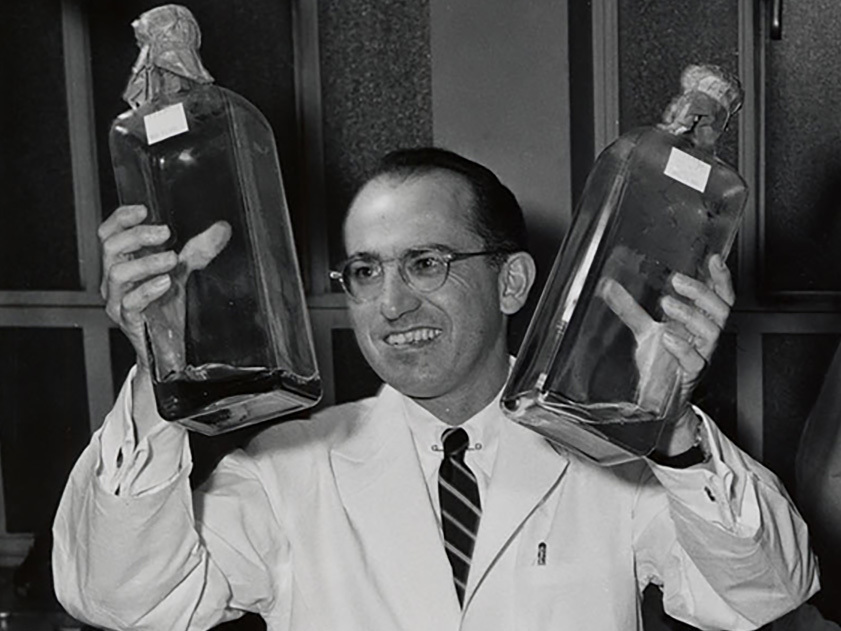

On April 12, 1955, church bells rang out across the country in a peal of music. After years of painstaking research, Dr. Jonas Salk and his team had developed a weapon against the terrifying virus that annually subjected thousands of children to illness and, in some cases, paralysis or death. In 1952 alone, there were over 57,000 new cases of polio; more than 21,000 of those victims suffered paralysis.

Like my grandmother, my mother Marita was born just after a surge in pandemic, which peaked in the summer of ’52. At that time, my grandmother already had four sons, including identical twins, peppering the house with dirty socks and the neighborhood with pranks and misdemeanors. But she longed for a daughter and she and my grandfather Tom, through happenstance or deliberation, risked a fifth pregnancy.

The following year, the year of my mother’s birth, Dr. Salk vaccinated himself, his wife and his three sons before involving 1.3 million children in field trials that proved his vaccine’s effectiveness. Immunizing his family, the virologist demonstrated trust in his own science. Like most parents, he sought to protect his children against the existential threat of disease.

One of my mother’s earliest memories, in fact, is receiving her polio vaccine series at a local school up the street from where I now live. She could sense her parents’ relief and even joy. It was, in effect, a secular baptism, a blessing that would safeguard her for life.

A generation later, we are again waiting in hope — and constraint — for a possible vaccine and for effective clinical treatments of a new viral infection, one that has emerged with blistering speed and severity. As a writer, I am used to spells alone, to having conversations on paper, to imagining narratives beyond the present moment. In many ways, my daily rituals have not changed. I teach my students through the aegis of a computer screen, but I write as I did before in hours at my desk or in the easy chair, books and papers in hand.

And I know exactly how I got here: I am the daughter and granddaughter of women who prized books and time in their company. My grandmother read avidly and, in the last decades of her life, undertook a theological education worthy of a Jesuit. Her reading table was stacked with texts from Aquinas to Newman, her large gray eyes trained on heavy tomes and on hundreds of notecards, carefully inscribed with pencil.

My mother, when she wasn’t herding us four kids in circuits of suburban sports and lessons, was constantly reading fiction, history and science. Both sought intellectual sustenance outside of their roles as wives, mothers and fixtures in their communities. They prized the privilege of being alone, tracking their own curiosities. It is a legacy seemingly as tactile as this sweater, passed down 80 years and worn by two women whose innate seriousness was shaped by pandemics: horizons of concern into which they were born and raised.

And so we shelter in place, imagining an end to our spells of isolation, holding out for another redemptive moment like the one inaugurated by Salk’s discovery. We remember how to be alone, how to populate our solitude, and how to trust that science and endurance will bring us to a better ending, one that insists — in a paschal fashion — on new life in death.

Heather Treseler is an associate professor of English at Worcester State University and a visiting scholar at the Brandeis Women’s Studies Research Center. Her poetry chapbook Parturition won the Munster Literature Centre’s Prize.