Naajmeddine Harrabi ’19 strides out onto an open stage. There’s a blue blazer draped around his shoulders and he wears a sparkly gold shirt underneath. Two black boots anchor him to the floor as he stares out at the Washington Hall audience, motionless.

“Hello, commoners,” he says.

It’s all a performance, of course. The actor portraying a wealthy Arabian prince actually grew up a poor shepherd boy in Tunisia. While the character brags about a red Ferrari his father purchased for him, the performer spent his childhood in a home where weekend video rentals were a luxury.

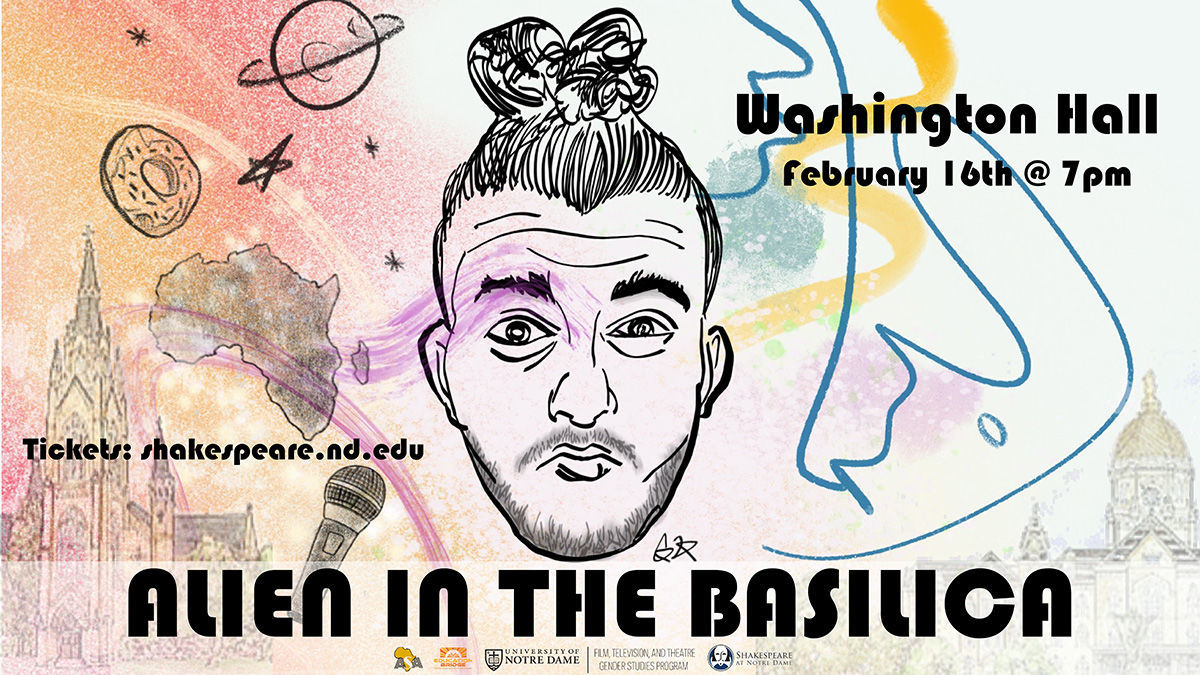

The performance is Alien in the Basilica, a stand-up comedy special written by Harrabi, who is now working on a master’s degree in film and television at the University of Southern California. The February 16 performance benefitted Education Bridge, an organization designed to support education in South Sudanese schools.

Harrabi — who worked with his grandfather as a shepherd while growing up in southern Tunisia — knows what it’s like to have limited access to education. When he was young, he thought there were two options for his life: herding sheep or joining the police force. It was only when his family moved to the city of Sfax when Harrabi was around age 12 that he could pursue the education he wanted.

Harrabi studied math in school, but his dream was to tell stories. He particularly liked the stories he watched on television. At first, it was Italian soap operas on a black-and-white television powered by a car battery when he lived in the countryside. When he moved to the city, Harrabi fell in love with Bruce Lee movies and other VHS tapes he could get his hands on.

Once, when his French teacher asked the class what career they wanted to pursue, Harrabi’s hand shot up. He told the class he wanted to be an actor.

“In my mind, that was the closest thing to greatness,” he says in an interview before his Washington Hall performance.

But Harrabi didn’t stand by the proclamation very long. “I remember [the teacher’s] face changing,” he says, “almost like disappointment, and I was like, ‘No no no no! I meant engineer!’”

While he concealed his interest in acting to peers and teachers at school, Harrabi did divulge his cinematic dreams at home. “My family heard me saying when I was a kid, when I was watching that black-and-white TV, telling them, ‘I’m going to America to make movies,’” Harrabi says.

“They really believe in me,” he adds.

Still, the young actor knows his relatives well enough to presume they harbored reservations, even if they never voiced them. “I’m sure somebody felt it and never said it,” he says with a smile.

Harrabi’s dream started to materialize in high school when his participation in a leadership initiative for young Africans connected him to Notre Dame’s Hesburgh-Yusko Scholarship Program. The program recruited Harrabi and he found himself bound for South Bend, one step closer to the silver screen.

The lights dim and a spotlight focuses on Harrabi, now dressed in all black. The performance’s tone shifts as the comedian transitions from jokes about the misery of Midwestern winters — comparing them to the looming apocalypse portrayed in Game of Thrones — to his experience as an immigrant.

Harrabi — who resides in the United States under a student visa — is quick to point out that he is, in fact, an alien. The Department of Homeland Security defines an alien as “any person not a citizen or national of the United States.” As a native of Tunisia who lives here on a temporary basis, Harrabi fits the definition.

Still, it’s not a term which he appreciates. “That’s kind of messed up,” he says.

He decided to incorporate the word into his show’s title, locating himself “in the Basilica” to illustrate his identity as a Muslim student at a Catholic school. Together, the phrase expresses a sentiment Harrabi has experienced for as long as he can remember.

“I never really felt like I belonged anywhere,” Harrabi says. “When I moved to the city, I was the kid from the countryside, and when I moved back to the countryside I was the kid who left the countryside to go to the city.”

When he arrived at Notre Dame, that isolation became more intense. In addition to the incongruity he felt surrounded by students who shared virtually no common background with him, there was also legal uncertainty.

During his first week in office, President Trump issued an executive order that halted “immigrant and nonimmigrant entry into the United States of aliens” from seven countries, including Libya, which borders Tunisia.

While his nation was not listed, Harrabi was worried. He saw no clear reason why those seven countries were chosen and he feared that, if he tried to visit his family, the slightest sign of unrest in his homeland would make a return to the United States impossible.

“At any point after submitting the list,” the executive order said, “the Secretary of State or the Secretary of Homeland Security may submit to the President the names of any additional countries recommended for similar treatment.”

As a result, Harrabi did not go home for three years. Even when he did visit his family during winter break of his senior year, he could not enjoy the time he spent with them, terrified of not being able to return and finish his education.

“You are always a slave to a piece of paper,” Harrabi says. “I don’t think it’s right.”

To make the matter more personal, the Muslim who played Jesus in a University theater production had a fiercely pro-Trump roommate. He recalls the joy his roommate and others felt when the Cubs won the World Series in November 2016, which became jubilation for their candidate’s victory in the presidential election a week later.

“That was a big reality check for me because I realized then that life is complicated. People may be nice, but . . .” the actor trails off. “I don’t know.”

Harrabi concludes with a joke about getting circumcised at age 5 and thanks his audience. The crowd breaks into applause as the performer clasps his hands and gives a slight bow.

The show he spent a year writing and rehearsing on a karaoke machine had finally come to an end, but its impact will travel beyond Washington Hall. A camera crew recorded Harrabi’s performance. The footage will be edited and posted on YouTube at a later date. The funds he raised for Education Bridge will help children in South Sudan receive a better education.

And he has made a little more progress toward achieving his dream, each step giving him more pride in his roots, a personal history he once considered an impediment.

“I remember, for a long time, I just hated being a shepherd. I just hated being known for that,” he says in our interview. “I love being a shepherd now, because I now know that everything I have become had to do with that experience. . . . I thought being a shepherd in Tunisia was my disadvantage, but it turned out to be my superpower.”

Harrabi references this advantage in his comedy show, claiming the “fresh goat milk” from his flock prepares him to confront prejudice, which he depicts in the character of a “racist squirrel” who defecates on him.

Over halfway through his first year of graduate school at the University of Southern California, Harrabi remains focused on his creative future, in which he envisions doing more stand-up comedy, directing films, writing plays. And he’s reading about developments in the way machine learning relates to art, mentioning a researcher who feeds images to a computer and lets its artificial intelligence algorithms dream.

“It's exciting, man, it’s really exciting,” he says, the elation evident in his smile. “Life is too short to say, ‘Oh, this is the path.’”

There is inherent uncertainty in any creative endeavor, especially uncharted ones, but Harrabi compares pursuing an array of interests to the way a shepherd sometimes follows his sheep, trusting that they will find food and water for themselves. “It’s dangerous,” he notes with a laugh. “Maybe not financially the best choice, but I think eventually things will be OK.”

As the show ends, Harrabi seems to have an expression of incredulity on his face as the audience whoops and applauds. It’s part gratitude, part awe. The look, perhaps, of a dream beginning to be realized.

Jack Lyons, a junior studying theology and journalism, is an intern for this magazine (now reporting remotely from his home in Vermont).