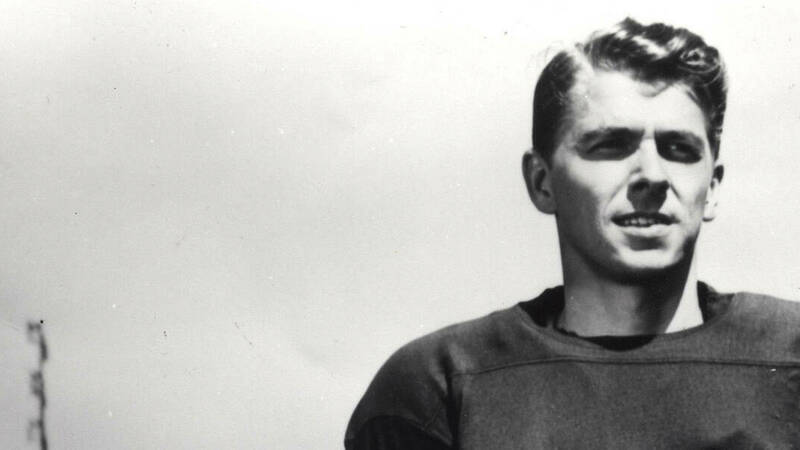

The 29-year-old actor’s resolute campaign to play a small yet memorable role in the movie about his hero showed determination that, decades later, directed higher ambition.

Throughout his youth a century ago, Ronald Reagan followed the life and career of a certain football coach. Then, after graduating from college in 1932 and working nearly five years in sports broadcasting, the Illinois native headed west to Hollywood. He carried with him a dream beyond acting.

“I wanted to tell the story of Knute Rockne,” Reagan admits in his pre-politics memoir, Where’s the Rest of Me? His ardor to bring Rockne to the big screen even drove him to try his hand at writing a script.

In his post-White House, 748-page autobiography, An American Life, Reagan confesses he “never thought about getting paid” for this aspiration. He wanted something other than money. “My reward was the part of George Gipp — the immortal Gipper.”

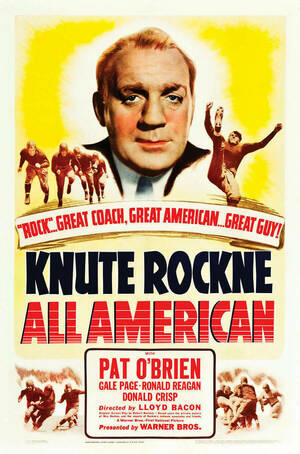

Little did the sports announcer-turned-actor know how portraying Gipp in the 1940 film Knute Rockne All American would contribute to Reagan’s third and most significant career. That connection, though, lay over a quarter of a century in the future.

Twenty years after Gipp perished in 1920, and nearly a decade after Rockne’s death in a plane crash on March 31, 1931, Reagan concentrated on what he would call, in an article for The Saturday Evening Post, “the role I liked best.”

Two principal reasons undergirded the actor’s enthusiasm for the part. Gipp, Reagan wrote, was “a man I had always admired” as “one of the greatest football players of all time,” and the portrayal served as “the springboard that bounced me into a wider variety of parts in pictures.”

The first Notre Dame All-American, Gipp played on offense and defense, becoming a triple threat with the ball for his running, passing and kicking. In 1920, his senior season, he averaged 8.1 yards per carry, still a University record.

Reagan “knew that playing Gipp could steal the show,” in the judgment of biographer Bob Spitz. “Never mind that George Gipp was a reprobate who drank, smoked, hustled pool, rarely practiced with the team, bet on Notre Dame games, and was expelled from the university for misconduct. In the movie version, he’d be a saint,” Spitz wrote in Reagan: An American Journey. Indeed, the Hollywood portrayal gave Gipp a status almost rivaling Rockne’s.

Reagan’s regard for Gipp’s athletic prowess and the football player’s stature as “a legend” who died young help explain the actor’s attraction to the role he coveted. Laying their lives side by side reveals that, despite conspicuous differences, Reagan and Gipp shared uncanny personal similarities as well.

Both men were born in Midwestern villages during the month of February — 16 years apart — and both grew to the height of 6 feet, 1 inch.

Both stayed in the Midwest to attend college and played football at their respective schools.

Both were “naturals” in their fields, showmen driven to display their talents to large audiences.

Both, according to their biographers, were friendly when dealing with other people but displayed little interest in forming close friendships.

Both would have naval vessels named for them. The SS George Gipp, a cargo ship, came into service during World War II, and the USS Ronald Reagan, an aircraft carrier, was launched in 2001.

Of course, what brings Reagan and Gipp enduringly together is a nickname. In each case that nickname, “the Gipper,” combines fact and fantasy — or, if you will, real history and reel history — that for Reagan served different purposes at different times. When he remarked in his 1965 memoir that with “the great ‘Gipper’” it’s “hard to tell where legend ends and reality begins,” he didn’t yet know how the dance between legend and reality would unfold in his own life.

Indeed, the nickname’s emergence into popular parlance is a tale involving dramatic invention and political appropriation. It begins nearly 100 years ago.

Gipp, it seems, was never “the Gipper” in life.Contemporary accounts chronicling his gridiron exploits refer to him in vibrant prose but without a commonly cited sobriquet. The opening sentence of The New York Times’ report about the 1920 Notre Dame-Army game at West Point highlights the talented running back in his team’s 27-17 victory: “A lithe limbed Hoosier football player named George Gipp galloped wild through the Army on the plains here this afternoon, giving a performance which was more like an antelope than a human being.”

Six days later — and in advance of Gipp’s final game at Notre Dame — the same paper christened him the “Babe Ruth of Football.” (In 1920, Ruth played his first season as a New York Yankee, hitting 54 home runs and batting .376.)

In Shake Down the Thunder, Murray Sperber’s history of Notre Dame’s emergence among the collegiate football elite, he notes that the breezy informality of “the Gipper” wasn’t heard around campus or in the locker room: “no one called Gipp by that nickname, nor did he ever use it for himself.”

Where did the moniker come from? At this point, myth and legend start to intrude on history, creating a timeless mystery.

When Rockne’s 1928 team faced Army in Yankee Stadium, the immortal coach was enduring his least successful season. Beating the Cadets might redeem Notre Dame’s reputation, so Rockne — either before kickoff or at halftime, accounts vary — provided motivation by retelling what he claimed were Gipp’s last words before his death eight years earlier.

Francis Wallace, who had served as Rockne’s press liaison as a student, headed east after graduating from Notre Dame in 1923 and became a New York sportswriter. Wallace’s story in the Daily News two days after the Army game appeared under this headline: “Gipp’s Ghost Beat Army — Irish Hero’s Deathbed Request Inspired Notre Dame.” Without knowing it at the time, he was contributing to the folklore about both Rockne and his late backfield star.

Calling Notre Dame’s 12-6 triumph “the most glorious in the history of the school,” Wallace quoted the coach directly: “On his deathbed George Gipp told me that someday, when the time came, he wanted me to ask a Notre Dame team to beat the Army for him.”

Wallace, who subsequently wrote several books about Notre Dame football, commented within his story about what Rockne purportedly said: “It was not a trick. George Gipp asked it. When Notre Dame’s football need was greatest, it called on its beloved ‘Gipper’ again.”

Had Rockne himself used the nickname when talking with the sportswriter? Did Wallace, who as much as anyone is responsible for Notre Dame’s athletic teams’ being called “the Fighting Irish,” give Gipp the endearing label? That’s unknown. What’s indisputable, however, is that the coach used the nickname frequently after that Army game.

Working with a ghostwriter in 1930, Rockne contributed eight lengthy articles to Collier’s, a mass circulation weekly. One feature, published on November 22, recounted the story of “Gipp the Great,” the only player singled out in the series.

Near the end of the coach’s remembrance, he recalls being in Gipp’s hospital room with other people. Suffering from strep throat and pneumonia, Gipp turned to Rockne, who describes what happened in one paragraph.

‘“I’ve got to go, Rock,’ he said. ‘It’s all right. I’m not afraid.’ His eyes brightened in a frame of pallor. ‘Some time, Rock,’ he said, ‘when the team’s up against it, when things are wrong and the breaks are beating the boys — tell them to go in there with all they’ve got and win just one for the Gipper. I don’t know where I’ll be then, Rock. But I’ll know about it, and I’ll be happy.’”

The Collier’s story would become almost word-for-word the deathbed request in the screenplay of Knute Rockne All American, and the words remain enshrined on a plaque in the home team’s locker room at Notre Dame Stadium. In this version, the appeal transcends a passion to beat any single opponent and invests the ill-fated athlete with the endearing nickname.

The actor who uttered it would be linked with it forever.

Reagan employed the nickname and its deathbed desire in different yet deliberate ways. Sometimes a jaunty jocularity prompted the appeal. Sometimes the line evoked a young actor’s Hollywood past and his identifiable involvement in the nation’s popular culture.

Interestingly, on three occasions in the movie before Reagan calls himself “the Gipper,” other characters refer to Gipp that way, followed by three other times after the hospital scene. Even off screen, Gipp remains central to the cinematic narrative — the other All-American, if you will. Reagan appeared in 53 movies, but his 10 minutes in the Rockne film became pivotal both to his acting career and to how people viewed him ever after.

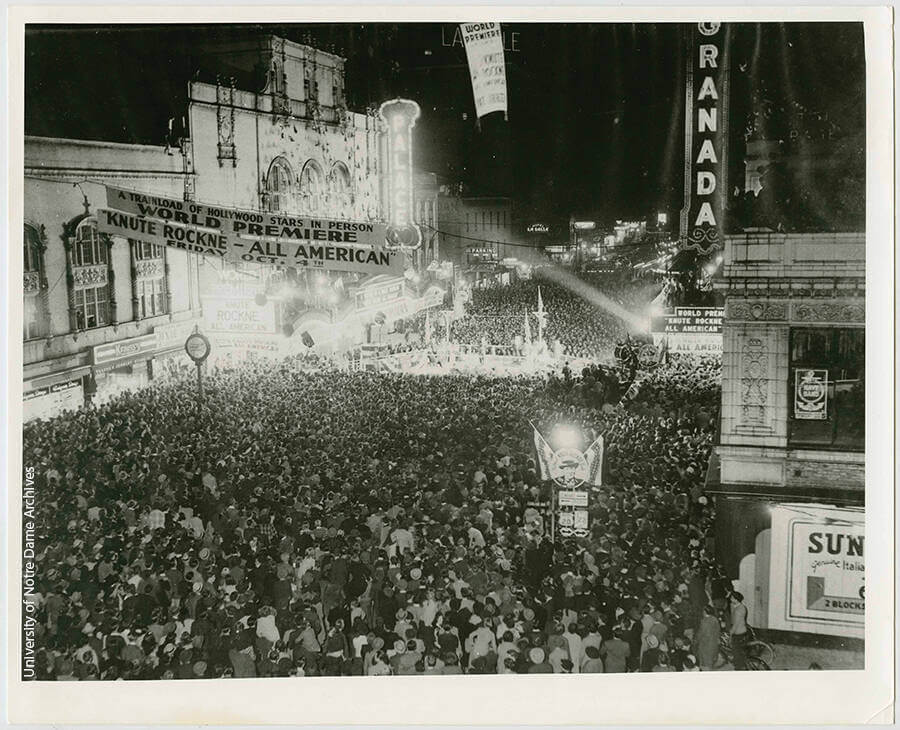

That identification took root on October 4, 1940, during the film’s South Bend premiere — an extravaganza that brought the cast, led by Pat O’Brien as Rockne, and other celebrities such as Bob Hope, Kate Smith and Mickey Rooney, to northern Indiana for what was ballyhooed as “Rockne Week.”

Four downtown theaters showed the movie simultaneously to about 10,000 people, while thousands more jammed sidewalks to glimpse the stars. The South Bend Tribune reviewer singled out Reagan as “outstanding in his well-suited role of George Gipp.”

Reagan, who’d grown up in Illinois being called “Dutch,” returned to California with a new nickname that had a direct relationship to the memorable athlete and the historic coach. The deathbed line also possessed inspirational adaptability. Two decades later, as Reagan segued from the glitz of show business to the hurly-burly of electoral politics, references to him as “the Gipper” began to appear regularly in journalistic coverage.

At the time, the shorthand seemed amusing, but it bordered on being disparaging.

In 1967, Reagan’s first year as the Republican governor of California, a wire service distributed a dispatch from Corvallis, Oregon. The Chicago Tribune headlined the item “‘Gipper’ to See O.J. Against Oregon State.” The brief story explained the situation: “George Gipp will be here tomorrow — and O.J. Simpson hopes to put on quite a show for the Gipper.

“Gov. Ronald Reagan of California, who played the legendary Halfback George Gipp in the movie version of Knute Rockne’s life, is traveling here to watch top-ranked Southern California meet dangerous Oregon State.”

As Reagan’s electoral ambitions expanded — after his second gubernatorial term ended in early 1975, he mounted an unsuccessful primary challenge against incumbent Republican president Gerald Ford in the ’76 election campaign — allusions to “the Gipper” multiplied.

In 1980, as the Republican nominee, Reagan took on President Jimmy Carter in the November election and soundly defeated him. Some political analysts looked more intently at the movie-related nickname that the charismatic politician and his supporters kept invoking.

These observers concluded that Reagan’s cinematic bond to Gipp and Notre Dame, originating with the Rockne film, helped attract ethnic Americans, particularly those of Irish heritage, to his side. These voters flexed their civic muscles in voting booths and received their own label: “Reagan Democrats.”

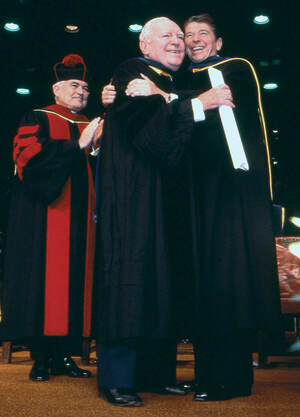

One event early in Reagan’s first term united the president and his nickname in an indelible way: Notre Dame’s commencement ceremony in 1981. Making his first trip outside Washington since a near-fatal assassination attempt on March 30, Reagan traveled to campus, in part, to recognize the 50th anniversary of Rockne’s death.

Inspired academic casting brought Reagan together with Pat O’Brien, “the Gipper” and “the Rock,” as honorary degree recipients. The president’s entrance into the Athletic & Convocation Center shook down a deafening thunder.

Introducing Reagan, Notre Dame president Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, combined civic empathy and university levity. “We welcome the president of the United States back to health,” Hesburgh began. “We welcome the president of the United States back into the body of his people, the Americans, and lastly, here at Notre Dame, here in a very special way, we welcome the Gipper at long last back to get his degree.”

Lou Cannon, who covered Reagan for The Washington Post and wrote several probing books about him, discloses in his biography, Reagan, the story behind the commencement address. He reports that the president “had on this occasion rejected the advice of aides who wanted him to talk about foreign policy, as President Carter had done four years before at a Notre Dame commencement. Reagan had written his own speech. What he wanted to talk about was Knute Rockne.”

Speaking about the coach, the president brought up a certain film and role. “I’ve always suspected that there might have been many actors in Hollywood who could have played the part better,” he acknowledged, “but no one could have wanted to play it more than I did.”

Though the president touched on favorite ideological themes (the evils of “excessive government intervention” and the necessity to “transcend communism”), the heart of his address centered on Rockne and Gipp: who they were and what they represented. At one point, after praising Rockne’s character, Reagan focused on the final statement attributed to Gipp — placing it in the context of the coach’s perspective.

“I hear very often, ‘Win one for the Gipper,’ spoken in a humorous vein,” the president said. “Lately I’ve been hearing it by congressmen who are supportive of the programs that I’ve introduced. But let’s look at the significance of that story. Rockne could have used Gipp’s dying words to win a game any time. But eight years went by following the death of George Gipp before Rock revealed those dying words, his deathbed wish.”

Reagan pointed out that Rockne was trying to lead “one of the only teams he had ever coached that was torn by dissension and jealousy and factionalism. The seniors on that team were about to close out their football careers without learning or experiencing any of the real values that a game has to impart.”

The president, knowledgeable about his subject, built to a moral with lasting meaning: “None of them had known George Gipp. They were children when he played for Notre Dame. It was to this team that Rockne told the story and so inspired them that they rose above their personal animosities. For someone they had never known, they joined together in a common cause and attained the unattainable.”

With 500 journalists trained on the 70-year-old commander-in-chief recovering from serious injuries, coverage of the ceremony proved enormous. Newspapers across America ran front-page stories, many brightening reports with photos of Reagan and O’Brien embracing on stage.

The most eye-catching headline on Page 1 of The Washington Post the next morning (over the story written by Cannon) summed up the ceremony in six words: “‘The Gipper’ Returns to Notre Dame.” The Chicago Tribune devoted an entire page to pictures of the presidential visit.

Reagan recorded his own account of the day in his diary. The commencement “really was exciting,” he wrote. “Every N.D. student sees the Rockne film and so the greeting for Pat & me was overwhelming. . . . I was made an honorary member of the Monogram Club. When I opened my certificate I thought they’d made 2 copies — they hadn’t, the 2nd was to ‘The Gipper.’ He died before graduation so had never been made a member.”

In his thank-you letter, Hesburgh brought up the mythology binding Reagan to Notre Dame: “The legend which you helped to create here, that of the Gipper, has been a living legend for every freshman who has ever come here to the University and seen the film which you helped to create. I hope that some day I might present to you an unexpurgated copy of this film which we recently found in our Archives. I think it might bring back many happy memories.”

True to his word, Hesburgh went to the White House in 1982 to give Reagan a restored print. The president then watched it in the company of Hesburgh and others, referring to the viewing in his diary as “quite an experience,” adding, “For me it was a truly nostalgic evening.”

Terence Smith ’60, author of a forthcoming memoir, Four Wars, Five Presidents: A Reporter’s Journey from Jerusalem to Saigon to the White House, covered the 40th president as a correspondent for CBS News. Looking back, he said in an interview, “Ronald Reagan thought of himself as ‘the Gipper,’ bathed in the image and used the phrase ‘Win one for the Gipper’ over and over.

“The image, and the legend, became part of Reagan’s personal portrait. He showed the movie to friends repeatedly in the White House theater, including one time when my wife, Susy, and I were among the guests. Susy sat next to the president in the first row — Nancy Reagan was away — and she said that he exulted in the film and the image. The Gipper was, quite simply, the way Ronald Reagan saw himself.”

Smith reported on the 1988 Republican National Convention, Reagan’s last as president and the one where his vice president, George H.W. Bush, was nominated. Midway through Reagan’s remarks, Smith recalls, the president created pandemonium by saying, “George, just one personal request: Go out there and win one for the Gipper.”

For three decades in politics, Reagan employed the nickname and its deathbed desire in different yet deliberate ways. Sometimes a jaunty jocularity prompted the appeal — and laughter. Sometimes a motivational intent sparked its utterance. Sometimes the line evoked a young actor’s Hollywood past and his identifiable involvement in the nation’s popular culture.

Inspiring a victory on the football field might have motivated what Gipp putatively said, but Rockne often shaped pep talks for larger ends. So did Reagan. His identity intertwined with Gipp’s; however, his invocations of the famous five words sounded more like Rockne, the coach that “Dutch” Reagan watched from afar in his youth and never stopped admiring.

In a way, too, it’s almost as though these two figures from Notre Dame’s football history merge in a singular appeal that — to the dismay of Reagan’s many critics — was usually intended to achieve political goals.

Reagan continued to show his esteem for Rockne by returning to Notre Dame on March 9, 1988, for the dedication of the Rockne postage stamp: the first to honor an athletic coach. In her recent biography, The Triumph of Nancy Reagan, Karen Tumulty reports that the first lady and her husband scheduled “sentimental visits to places that had been important to his life and his presidency” during his final months in office. Near the top of the list of “symbolic milestones” for Ronald was a trip to Notre Dame to mark the 100th anniversary of Rockne’s birth, providing, of course, “a chance to reprise the movie line” that had become Reagan’s “political battle cry.”

En route to campus from the South Bend airport, the president told Rev. Edward A. Malloy, CSC, ’63, ’67M.A., ’69M.A., who succeeded Hesburgh as University president the year before, about his first visit to Notre Dame in 1934 as a play-by-play radio announcer at a football game. Today Malloy remembers how Reagan reminisced about players on the Irish team nearly a half-century earlier and how “he seemed to have a special affinity for Notre Dame.”

In his stamp-dedication speech, Reagan amplified his 1981 commencement themes. Near the beginning, he said the coach had been “a living legend,” adding that “the Rockne legend stood for fair play and honor, but you know, it was thoroughly American in another way. It was practical. It placed a value on devastating quickness and agility and on confounding the opposition with good old American cleverness.

“But most of all, the Rockne legend meant this — when you think about it, it’s what’s been taught here at Notre Dame since her founding: that on or off the field, it is faith that makes the difference, it is faith that makes great things happen.”

Then, just before uncovering a poster-size likeness of the stamp and tossing a football into the crowd, Reagan concluded his half-hour of remarks by reciting, in full, what the coach had said were Gipp’s departing words. In his diary, the president wrote: “It was a wonderfully sentimental day.”

During his second term as president, Reagan couldn’t escape being associated with his movie-inspired nickname, nor did he try to escape from it. When he was released from the hospital after cancer surgery in 1985, he returned to the White House and wrote in his diary that “more than 1000 staff & family, the Cabinet etc. were waiting with music, balloons & wonderful signs — many invoking the name of the ‘Gipper.’ This too was moving — I’m a very lucky man.”

A year later, a Hollywood friend wondered in a letter whether Reagan was still “interested in Gipp.” The president answered by saying the football star “has remained very much a part of my life, indeed playing him was the role that moved me into the star category. Curiously enough, at political rallies during my last campaign there would always be signs out in the crowd referring to me as ‘The Gipper.’ And believe me, I liked that very much.”

Fittingly, one of Reagan’s last commitments before leaving office in early 1989 was a White House celebration for the 1988 national championship Notre Dame football team. In his welcome, Reagan offered a personal coda to his decadeslong relationship with the school that played something of a supporting role in what he’d become.

“My life has been full of rich and wonderful experiences,” the president said. “And standing near the top of the list is my long and honored association with the University of Notre Dame and its legendary hero Knute Rockne. So, I want you to know the INF treaty [the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with the Soviet Union that took effect in mid-1988] and George Bush’s election [in November of ’88] were important, but having the Fighting Irish win the national championship is in a class by itself.”

At the end of his remarks, Reagan looked back to Rockne and his star player: “Right now, I can’t help but think that somewhere, far away, there’s a fellow with a big grin and a whole lot of pride in his school. And he might be thinking to himself that maybe you won another one for the Gipper.” The line produced laughter, but this time, and uncharacteristically, the presidential “Gipper” was referring not to himself but to the real Gipp.

In the Rose Garden ceremony, Malloy surprised Reagan by presenting him with George Gipp’s monogram sweater as a gift. Taken aback, the president remarked, “I think that’s a great sacrifice by the university. But believe me, no one could have it and treasure it more than I will.” The sweater, a source of controversy among people opposed to Notre Dame’s giving it away, was later placed on display at the Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in California.

When Malloy is reminded of that sunny January day at the White House, he recalls how “genuinely moved” Reagan was to receive the sweater, principally because of his strong “personal sense of identification with Notre Dame.” The president had graduated from Eureka College in Illinois, but it was another school in a neighboring state that had contributed most significantly to his national identity.

Nicknames abound in American presidential history, making the chief executives in our democratic republic less remote and closer to the people. Some are spoken with a smile (“Old Hickory” or “Ike”), some with a snarl (“Tricky Dick” or “Slick Willie”). “The Gipper” is unique in how it was born and how it came to be used.

From 1940 onward, Ronald Reagan’s nickname took on a life of its own and helped define him in the public mind. Through its appeal and aspirational message, he tried to keep scoring wins, one by one. The deathbed desire uttered by a fledgling actor became, over time, a rallying cry for the nation’s leader.

Bob Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor Emeritus of American studies and journalism at Notre Dame. He’s the author or editor of 15 books, most recently Fifty Years with Father Hesburgh: On and Off the Record and The Glory and the Burden: The American Presidency from FDR to Trump, both published by Notre Dame Press.