It’s a vertiginous time to be an American. Often, over the past several years, it has felt like our country is hurtling headlong through a bruising gauntlet of crises, still dazed from one even as the next one strikes. Some troubles, like the coronavirus pandemic, seem basically natural — new iterations of age-old human afflictions. But others — mass shootings, widespread alienation and loneliness, the loss of trust in our institutions, political polarization, wealth-hoarding and conspiracy theories — are correlated to our time and place, and feel, in ways hard to pin down, deeply interconnected, like aspects of one single disintegration. In an apocalyptic mood, one might be reminded of W.B. Yeats’ famous interwar cri de coeur: “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold.”

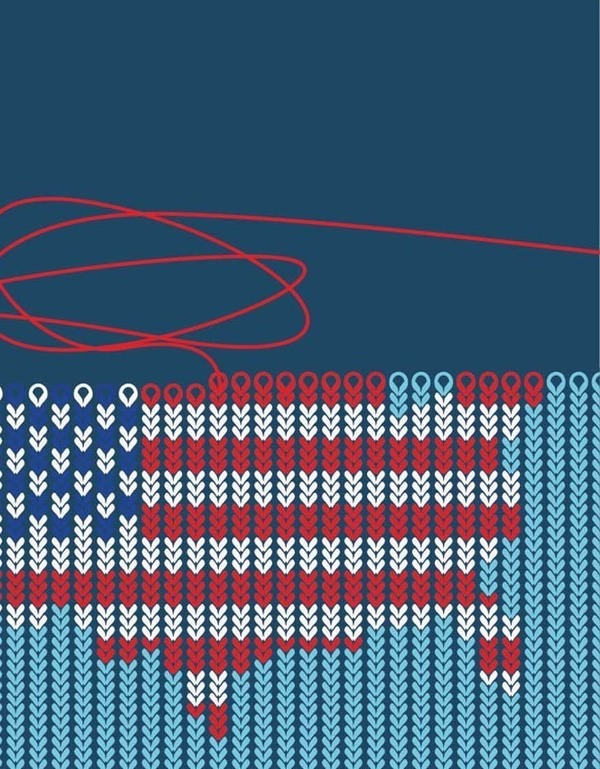

What is the nature of this falling apart? We might begin to think about that bewilderingly large question by following one important thread through the crises I’ve listed: the spreading, gut-level sense of precarity; the feeling that I am alone, that I could fall, and fall hard, and there would be nothing and no one there to catch me. In recent years this anxiety has spread beyond the lower classes, unsettling even the relatively wealthy and secure.

I see this anxiety in my students. Every semester for the past few years, I’ve taught a required introductory course at an elite undergraduate business school. The course combines business ethics with a broad examination of what work, commerce, success and money really are. I start the term by asking each student what he or she is studying, and always the overwhelming majority replies, “finance.”

I then ask why. As a philosopher intruding on unfamiliar territory, I initially expected my students to be aspiring Wolves of Wall Street, Gordon Gekkos, John Galts, ravenous empire-builders, megalomaniacs, what have you. Instead, nearly all these intensely bright, privileged students say they study what they do because it seems safe, seems likely to win them a steady and lucrative job after graduation, which in turn will buy them and theirs some stability and security in life. This is the language they use, with very few exceptions.

This past semester I added a third question: What would you do if money were not an issue?

Their answers to this were exactly what a philosopher might expect. Every one of my 15 students said they would study the arts or humanities or the natural world (allowing for one would-be race car driver and one mountaineer). Adventure, beauty, the body, wisdom, the world: Young people today have the same thirsts I recall from my own late adolescence. But the kids I teach, at least, are petrified. They wouldn’t dare spend $90,000 a year pursuing something so fulfilling and “impractical.”

Their pervasive concern with economic safety and stability goes a long way toward explaining the steady growth of finance, economics, engineering and computer science majors, concurrent with the total withering of majors in philosophy, literature, art and religion. It also helps to explain the collapse of American innovation that The Atlantic writer Derek Thompson and others have recently observed: Across sectors like scientific research, filmmaking, entrepreneurship and governance, Americans have stopped taking the risks necessary to make and discover new things. Rates of business formation, to cite one example, have been falling since the 1970s. This is to be expected; a precarious, risk-saturated environment encourages wagon-circling and conformity, not brave innovation.

A turn to a more solidaristic, less precarious way of life cannot simply be effected by technocrats. It requires Americans to rediscover what we love together, to locate anew our unity as a people.

Why do we feel so unsteady, so risk-exposed, here in the wealthy United States of America?

Our lives are, at a fundamental level, fragile and finite things, of course, but under conditions of broad-based plenty, feelings of precarity can largely dissipate or go dormant for significant stretches of time. But while Americans have witnessed massive expansions of wealth over the past few decades, these expansions have been anything but broad-based.

In 2020, Time magazine reported an “upward redistribution of wealth” of $50 trillion since the 1970s, an abundance taken from the bottom 90 percent of households and delivered to the top 1 percent. Meanwhile, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, CEO compensation shot up more than 900 percent while worker compensation climbed a modest 11.9 percent. While the few experience extraordinary prosperity, those in the middle and bottom of the socioeconomic hierarchy are accordingly beset by feelings of scarcity — as well as the feeling that this scarcity is artificial, that the game is, as an all-too-familiar political saying goes, rigged. If my students express more anxiety than rage, it’s because they still have a fighting chance of finding themselves among the 3 to 4 million Americans for whom the economy is working very, very well.

Why has wealth been pooling this way? Well, economies have a way of changing, of course. Some sectors die while new ones spring to life. Consider our one truly dynamic sector of late: digital technologies. Who knew, a few decades ago, that fiddling with computers could make you a billionaire many times over? But current American inequality is in large part no accident of the marketplace or of anything else; rather, it’s the result of concrete decisions made by human beings, those who sit on the boards of large corporations and those who legislate trade policies and tax structures, their election campaigns directly financed by wealthy corporations and individuals. These decisions add up to a social compact marked by abundance for those in power — and scarcity for the rest.

In some cases, scarcity may be used intentionally, as a goad. My students, for instance, are familiar with school-mandated grade curves that sharply limit the number of A’s available for distribution, effectively making scarce a good — educational success — that under normal circumstances is a shared good: One student’s growing comprehension contributes to her classmates’. But under our system, students must compete tooth and claw for a few scarce A’s, which are necessary to land the few good jobs that will allow them to amass personal wealth and build a secure life for themselves and their families.

The result is a shark tank of manic, anxious, ineffectual effort that leaves very little room for authentic learning. It takes almost superhuman effort to bravely, patiently open yourself to new truths, whatever they may be, however they might change you, when you’re fighting like a dog to find a place among the safe 1 percent.

It is possible for a group to experience some scarcity without individual members feeling alone and unsafe. Most families function this way; some communities do, too. Such groups are bound together by solidarity, the voluntary sharing of risk. If a woman loses her job and her spouse does not, she will not likely have to forgo food and shelter while the family carries on in comfort. Families pool risk and resources, so each person is protected by membership in the group. This sort of risk-sharing is natural, and native to us. No human being would survive to adulthood while facing the vicissitudes of reality alone.

That such assumptions of solidarity often end at the borders of the nuclear family is a modern innovation. In most times and places, they have extended much further. During the high days of European colonialism, for instance, colonizers who wanted to recruit indigenous people as wage-laborers had a hard time finding takers. One solution proposed to offer native peoples the option either to sell their labor or starve, but this approach stumbled upon a massive problem: Would-be employers could not find communities that would allow one of their own to starve as long as the group had food. Some recruiters forced the issue by peeling individuals away from their tribe or village, making starvation a live option and wage-labor the necessary remedy.

In modern, industrialized societies, we no longer organize our lives within solidaristic tribes. Over the past couple hundred years, different structures such as churches, unions, extended families and groups of close friends have, to varying degrees, replaced this older kind of group solidarity. In most cases, it requires some deep, commonly held sense of value and mission that binds members together in a collective identity and means that the good things they get are not zero-sum but shared. Many Americans feel this solidarity should happen at the level of the nation — that we should distribute risk and reward on the basis of our shared Americanness — and lament that it seems not to work that way.

But why not? Since the Founding, a few main stories have circulated about exactly who and what we are as Americans, what we love, what we’re pursuing together as a nation. Those fables of our civil religion all seem to have grown stale, becoming casualties of changing demographics, economics, folkways, values and beliefs. In the absence of deeply shared values, the existence of a strong and threatening common foe like, say, Soviet Communism or terrorism may bind a people together. Lacking even that, we have quickly come to see how little we share. These nation-level shifts have happened alongside a general thinning of solidarity at the level of churches and neighborhoods, even as our shrinking families lose stability.

The thinning out of local, communal solidarity is a tale as old as industrialization. For most Westerners, it’s been several generations since changing patterns of work pulled individuals out of long-settled villages where everyone knew everyone, and people were firmly embedded in solidaristic networks of family and church. One common, compensatory move has been to shift a great deal of risk-sharing upwards, across ever-greater numbers of people who are bound together less by voluntary solidarity — by love for each other or some shared goal — than by contract. In this model, insurance companies, unions, corporations, even the nation-state stand in for the older, more organic bonds of village and family.

This approach can work well enough. Knowing you’re safe because your company is bound by contract to pay out a defined-benefit pension to you and yours may not be as heartwarming as membership in a large family, but it still offers reasonable insulation from destitution.

Unfortunately, risk cannot be eliminated, at least not in this valley of tears. It can, however, be moved around. If the great modern ameliorative move has been to shift risk upwards, a distinct countermovement has emerged. Corporate America, it turns out, doesn’t like bearing risk any more than you or I do. The great goal of “de-risking” our institutions has really meant a measurable, concerted movement to push risk downward from institutions and back onto individuals. Safety nets and employment protections have been slashed, unions have been routed, pensions have given way to the market-exposure of the 401(k), leaving individuals directly exposed to the whipping welter of precarity and risk.

Signatories to contracts are legally bound to fulfill them. General Motors was not exercising love or goodwill in the 20th century when it kept its word and paid out its pensions. But the crafting of contracts can be inflected by a spirit of solidarity. In the 2020s, however, our society increasingly expects each person to go it alone, and our contracts reflect that.

My students behave rationally, then, as they scramble to amass personal wealth. What else could grant them a modicum of security for their families?

If these institutional changes are objective and measurable, then we have the insight and tools we need to change them back, to make Americans feel, once again, as if their fellow citizens (or at least their institutions) will look out for them when times are hard. But do we have the will? A turn to a more solidaristic, less precarious way of life cannot simply be effected by technocrats. It requires Americans to rediscover what we love together, to locate anew our unity as a people.

One realm in which we are seeing such a rediscovery is in class solidarity. Union petition filings were up 56 percent last year. I call this a welcome rebound, long overdue. The decades following World War II exhibited remarkable economic solidarity among Americans, and unions played an important role. Corporations shared their rising profits with workers via wage increases and more generous pensions. As a result, many families could afford to rely on lone breadwinners. The share-the-wealth ethos probably had something to do with fellow-feeling among exultant World War winners, but the decisive push came from organized labor.

Then, in the 1970s, business and government conspired to crush the labor movement. It may be that the growing interest in labor unions today is a sign that the beneficiaries of massive wealth concentration have overplayed their hand, that some portion of the precariat’s anxiety and rage will now be turned to workplace organizing.

This would be a good thing, a tremendously good thing. The lived experience of economic precarity is damaging on many fronts, not least in the widespread and not-incorrect perception that the game of our wealthy society is rigged by powerful actors. If I live in a resource-rich environment where some enjoy incredible luxury while I labor on in fear and weakness, I have every reason to think I am not surrounded by people with whom I share an identity, mission or destiny. The cause of fixing our economic life is a good one, and the history of the labor movement shows it can motivate sustained common action.

Solidarity focused on simple economic need is only one part of what America needs to build in the coming years if we are going to stop lurching from crisis to crisis or simply avoid falling apart altogether. If you and I are being mistreated and underpaid, we might very well band together and stick it to the boss. But the most successful labor movements have called their members together over more than money. They have offered a common, compelling way of life — one of craftsmanship, of excellence, of deep and genuine fraternity and mutual care.

Religion has often been intimately involved. The tasks of spiritual and material reconstruction are inextricably aligned. Humans are biological and social animals, and just as we would not physically survive alone, we can neither make nor maintain a world-picture — a sense of what is valuable and worth pursuing — alone. To inhabit a material-cultural world marked by individual precarity is to open up a solidarity vacuum prone to be filled by psychotic politics, mob dynamics, punishing polarization, racial chauvinism, chemical dependencies and other ills. And if precarity is the material manifestation of a lack of solidarity, then loneliness and alienation — along with a raft of knock-on dysfunctions, ranging from cardiovascular disease and diabetes to depression, as recently publicized by U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy — are the medical, mental and spiritual counterparts.

And yet, it is far from assured that Americans will in fact work together to forge a new spirit of solidarity. A deep, shared sense of what is true, good and beautiful — the cultural glue that holds a group together — cannot be easily forged via slogan, billboard or even curriculum. When a vision grows stale for a people, they may yet be pressured to mouth allegiance to it, but they cannot be forced to believe in it. We live in such a moment, and the various combatants in the culture war are swinging their worldviews like cudgels. They are inflicting pain, to be sure, but making very few converts.

Group chauvinisms, like racism, nationalism or the demonization of political opponents, often look like a sort of triumphalism, an uncompromising belief in the greatness of my group. But cutting through appearances, social scientists have found that belligerently nationalist peoples are actually motivated by what they call “collective narcissism,” a deep need for recognition and affirmation. Bellicose sniping among groups is not then a sign of strength but of weakness, of a group with a brittle sense of itself. Such an identity is not flexible and healthy. It cannot be adapted to take in new developments and information. Instead, such groups try to shore themselves up through remonstrations of their own superiority.

This sense of insecurity and all the manic, insecure attempts to feel a sense of belonging are pervasive. What can we do about it?

If material solidarity and shared identity generally come as a package deal, we have no clear order of operations for fixing them. We need concrete policies and practices that can make Americans feel less exposed to the storm of material risk. And at the same time, we need moral and spiritual renewal, reform, a reframing of our world-pictures.

This reframing could happen at the level of the nation. Perhaps a Ralph Waldo Emerson, a Walt Whitman or a Martin Luther King Jr. lives among us who can help us reimagine what it means to be us and articulate it in a way that captures the hearts of 300 million-plus people.

In the meantime, we also need renewed visions in our communities — our churches, families, neighborhoods and schools. Like MLK in Birmingham jail, Christ in the desert, Thoreau at Walden Pond or Dostoevsky in Siberia, we need leaders who can step back from the toss and turn of daily life and our virulent politics and ask afresh who we are and what we care about together, and answer in a way that makes our belongings feel strong, deeply bonded. None of this will be simple or quick. But it is the task handed to us by our moment in history, the only way to draw our season of precarity and whack-a-mole crisis management to a close and to inaugurate a period of civic creativity, solidarity and genuine, shared growth.

Ian Marcus Corbin is a philosopher on the neurology faculty at Harvard Medical School and a senior fellow at the think tank Capita. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The New York Times, Newsweek and Plough.