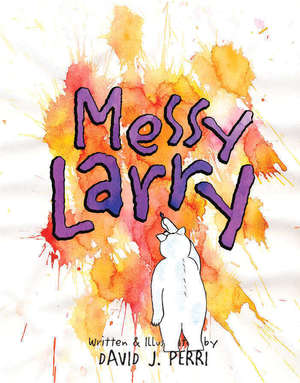

Never mind what his wife thinks, David Perri ’91 is here to set the record straight about his children’s book featuring a big, clumsy kid with artistic inclinations who kind of looks like a bear.

“Not autobiographical,” Perri says. “I just want to make that clear right now.”

The hero of Messy Larry takes some real-life inspirations, plural, from Perri’s personal experience, and the author shares his character’s need to create, but the story is drawn from his imagination.

A U.S. attorney by day in Wheeling, West Virginia, Perri is a painter at heart. The creative outlet is more central to his self-concept than is his profession. “I’m basically an artist who happens to be a lawyer,” he says.

It’s not that he aspires to paint for a living; it’s just that without the canvas on which to express himself, he wouldn’t feel fully alive. By way of illustrating its importance to him, Perri asks people who might have a similar relationship with music or literature or theater to imagine a world without that art form.

“If your knee-jerk reaction to that is maybe just a hint of panic, I think then you’re on the right track to understanding what I’m talking about,” Perri says, “because you’d be drastically a different person.”

Larry, the protagonist of Perri’s debut book, faces the frightful prospect of life without his artistic love. He fumbles, stumbles and sneezes, spattering the people and the tables and the walls all around him with color, bringing ridicule from the other kids — that, he could live with — but, worse, banishment from the source of his inspiration.

And Larry was sorry,

and Larry felt bad.

But, if Larry felt anything,

Larry felt sad.

He tries to imagine a way out of the mess, to no avail, until he visits his Great-Uncle Ken, who turns Larry loose in what looks like a garage, “a place crammed with all sorts of things” that would normally be a danger to himself and others, among them shelves of paint cans and brushes. And Ken says, “Here’s your chance; you can do it. Just be yourself.”

Larry makes and takes his predictable spills, sloshing no small amount of paint all over himself. Free from the shame his blundering causes in school, though, he also covers the walls in the masterpiece he knew he had in him. And what fun Larry has in the sloppy process.

Perri’s a different kind of artist than Larry in style and tidiness — not autobiographical, remember — but the two artists share the utter joy of just painting. Always interested in art, Perri dabbled in high school, but the painting classes he took at Notre Dame lit a flame he has fanned ever since. Riley Hall of Art, where he took enough classes to have earned a minor, had the University offered such things back then, remains a landmark he returns to like a pilgrim on campus visits.

“It’s still probably one of my absolute favorite places on the face of the earth — specifically the painting studio,” Perri says. “Oh my gosh. Just the smell of it, everything.”

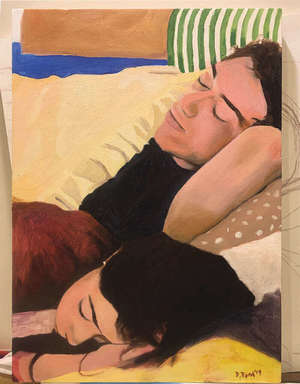

His painting style, distinct from what he’s heard described — aptly, he thinks — as the “naïve” quality of his Messy Larry illustrations, is impressionistic. His subjects are often scenes he observes in passing that stay with him until he renders them on canvas. A couple embracing on the sidewalk. His sleeping children. Something catches his eye and latches onto his subconscious.

The book was like that. Snatches of verses would float through his mind, and he’d jot them down in a folder of ideas. That’s where they stayed for years. A children’s book appealed to him, but it languished until a “now or never” urge rustled him. Now his second book, Kameron Gives a Kiss, is in the works.

These books are just a sideline to his sideline — pale moonlight compared to Perri’s paintings, but with a brightness the adult art world does not offer. He recalls one especially gratifying visit to a kindergarten class, the guileless and enthusiastic way the children engaged with the themes. “Their reactions to the different illustrations and the story was just so spot on to what I had hoped,” he says. Hard to beat that.

Few of his legal colleagues, Perri notes, share such artistic fervor. He imagines the reaction of coworkers browsing the 26 paintings he exhibited at a coffeehouse: “How come this guy doesn’t have, like, fingers?” Or, “How many paintings of hibiscus flowers can you possibly do?”

For Perri, though, the creative impulse seeps into his professional life in productive ways, even if it might not appear so on the surface. Doodling during dull meetings, for example, could inspire differing interpretations.

“Somebody might look at that and say, ‘Oh, he’s not paying attention,’” Perri says. “But that’s completely wrong, because I’m doing that so that I can pay attention. That make sense?”

If there’s an element of distraction in his artist’s orientation, he’s convinced it benefits his law practice. The qualities of observation, of sifting scenes to their essence, of capturing human experience in evocative images serves him in court. Writing legal briefs, questioning witnesses, persuading juries, Perri says, he’s painting pictures. Before a judge, a canvas or a kindergarten class, the objective is the same. “If you can help them to see a big picture,” Perri says, “it has much more impact.”

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.